Due to constraints on manuscript length, the “Post-Coronado Presence” section, as published in the Winter 2009 issue of the New Mexico Historical Review, is unavoidably much abbreviated from the material I submitted. Readers interested in my more comprehensive account, which includes maps, photographs of actual places named in historical documents, and additional written information and translations, are offered this expanded, although unedited, version of that section.

My research for this section was generously guided and strongly influenced by Bernard L. “Bunny” Fontana, to whom I offer my warmest gratitude. Of course, any errors or omissions are entirely mine, as are the interpretations and conclusions presented.

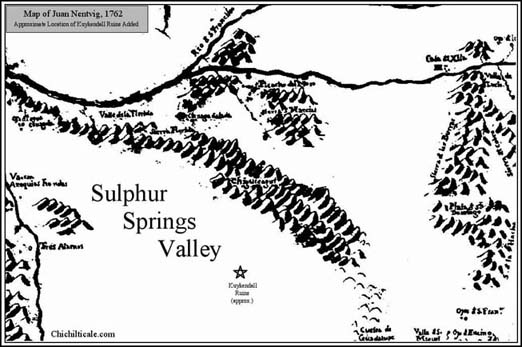

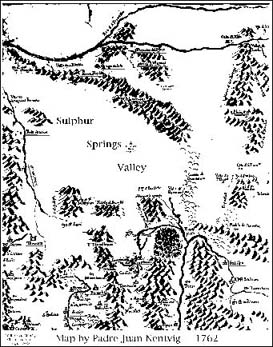

For over 400 years after Coronado left Chichilticale in 1542, the Sulphur Springs Valley remained a remote region seldom visited by outsiders. (53) Geologist O. E. Meinzer provided a succinct appraisal regarding non-native American presence in the Sulphur Springs Valley before 1853. “Up to that time and until about 20 years later it was occupied almost exclusively by the Chiricahua Indians, who were among the most warlike of the Apache tribe and who, according to some authorities, were the fiercest Indians on the continent. Consequently this region was avoided by the Spanish explorers and missionaries and later by Mexican and American prospectors and settlers.” (54) Jesuit priest Juan Nentvig afforded credibility to the claim of Meinzer by providing a graphic description of the inhabitation of the Sulphur Springs Valley on his 1762 map. The region is displayed as obviously empty – totally devoid of place names. Only the Chiricahua Mountains are indicated, these spelled Chiguicagui. (55) [I have added to the map the names Sulphur Springs Valley and Kuykendall Ruins to accommodate the reader.]

A historical summary of non-Native American domestic presence in the Sulphur Springs Valley prior to the early 1870s is warranted for the purpose of exhibiting the overwhelming lack of domestic presence. Anthropologist Edward H. Spicer offered such a summary for the years 1650 to 1853. (56) Spicer wrote that as early as the 1650’s there existed in northeastern Sonora a de facto economic border between the prosperous agricultural Opatas on the south and the nomadic Indians on the north. “Just north of this line of agricultural settlements in the 1650’s was something of a no man’s land.” The six or more tribes of Indians occupying this northern region included the Sumas and Jocomes, the latter “possibly a band of what later came to be called Arivaipa or Chiricahua Apaches.” (57)

In the early 1680’s trouble increased between the Sumas and the Spaniards. The late historians Thomas H. Naylor and Charles W. Polzer described the events surrounding this time. “[The Suma Revolt] flared in the spring of 1684 at Janos and Casas Grandes, and during the summer spread east… to other centers south of El Paso.” (58) In another passage the two historians wrote that the troubles “infected a large area to the south, and in the spring and summer of 1684 pressures came to a head… The hostilities spread to include Conchos and Chinarras, and the always belligerent Tobosos and Salineros were quick to join in.” (59) These reports suggest that Spanish military activities during the Suma revolt did not expand west of Janos to the Sulphur Springs Valley.

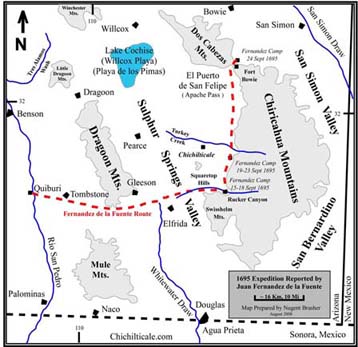

The Franciscan mission built in 1663 at Janos was destroyed during the revolt. Consequently a presidio was established there in 1686 and another one at Fronteras in 1692. Troubles did not lull despite the presence of these two presidios. In 1695 a relatively minor incident erupted into a major military excursion; dissident Pimans killed the Jesuit priest at the new mission in Caborca, an event followed by a low-ranking officer killing forty-nine Pimans attending a peace talk. The Pimas revolted and the governor of Nueva Vizcaya ordered a full-scale military campaign into the region. The campaign lasted four months, during which time detailed daily records were written by the commanding officer of Janos presidio, Juan Fernández de la Fuente. The Fernández reports described the Spanish presence in the Sulphur Springs Valley during middle September 1695.

Anthropologists Naylor and Polzer picked up the Sulphur Springs Valley portion of the story as the campaign departed Quíburi, located along the Río San Pedro near modern Fairbank, Arizona. “From Quíburi the army threaded its way east through the Dragoon Mountains and across the Sulphur Springs Valley. Lieutenant Solís led an advance party to scout for watering places along the western side of the Chiricahuas.” (60) Using my translations of the Spanish record of the days later in September 1695 to interpret the Spanish whereabouts in the Valley, I suspect that the troops and their Indian allies most likely crossed the Dragoon Mountains at their south end near modern Gleeson, Arizona. (61) The soldiers continued almost due east, passing south of Squaretop Hills and sliding by the north end of the Swisshelm Mountains to reach a camp on Whitewater Draw on Thursday, 15 September 1695. Their camp was “in this arroyo that leaves the Chiricahua sierra.” (62) Although Naylor and Polzer did not provide the actual daily records from the end of activities on the 16th until the morning of the 20th, I interpret from their English commentary that on the 19th the encampment was moved to “a large waterhole three leagues to the north.” (63)

The troops worked from this second camp until 24 September 1695. That day Fernández ordered the camp broken, and he first dispatched Lt. Solís northward to reconnoiter all the way to “the pass that is between the said sierra [Chiricahua Mountains] and the sierra of the Animas [Dos Cabezas Mountains].” (64) Fernández and troops then departed. When they reached the pass they turned east and entered the mountains, “and continuing with the march, we fell into the valley we call San Simón.” In his report written at camp that night, Fernández reported “having traveled more than six leagues to the north over flat land and some three leagues of traverse through the sierra to its eastern side.” (65) The morning of the 25th Fernández reported his position as “in this arroyo in the pass that makes itself between the Chiricahua sierra and the sierra of the Animas that today we named so that it will be known in the future as el Puerto de San Felipe.” (66) I interpret San Felipe Pass to be modern Apache Pass, and that the Fernández camp on the night of the 24th was at the mouth of Siphon Canyon.

Given this interpretation I am able to predict the locations of the two camps on the western side of the Chiricahua Mountains south of Apache Pass. Fernández wrote that he traveled six leagues over flat land before reaching Apache Pass. This description fits the eastern side of Sulphur Springs Valley along the western front of the Chiricahuas and places the camp of September 19th through the 23rd on modern Ash Creek or extinct Ruins Arroyo at a location about eight miles (13 km) east of Kuykendall Ruins. The camp the nights of the 15th through the 18th was three leagues south. This puts the camp on Whitewater Draw at Rucker Canyon. If my interpretation is correct, then Kuykendall Ruins were not campsites of the 1695 Spanish military campaign in the Sulphur Springs Valley. Moreover, the account of Fernández reports that excursions by his troops from those September camps were to the north, not the west, suggesting that Kuykendall Ruins was not visited by Spanish horsemen either. It follows that Spanish artifacts we found at Kuykendall Ruins are not likely the remains of a 1695 Fernández presence.

In December 1696, Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino first visited the Quíburi region. The padre left a few cattle for the Christianized Indians. He returned to Quíburi in March 1697, at which time he notified them that they should be ready to accompany the soldiers against the enemies of the province, mainly the Jacomes, the Janos, Sumas, and Apaches. (67) Padre Kino was back at Quíburi in the fall of 1697, when he and a score of soldiers from Fronteras traveled along the Río San Pedro, described as “pleasant and fertile… though much harassed by the Jacomes and Apaches in the east.” (68) These reports augment the description by Spicer of conflict between the Spaniards and the Indians east of the Río San Pedro. By 1705 the Spaniards dropped the name Suma and began referring to the raiding Indians as Apaches. “People whom the Spaniards called Apaches emerged as the dominant group north of the Opata villages as far as Zuni.” (69) These are the people referred to by Arizona cattle historian J. J. Wagoner when he wrote, “During the time of Kino, and in fact until 1873 when the Indians were finally put on reservations, the hostile natives constituted the chief retarding force to the white man’s attempt to Christianize and exploit the region south of the [Río] Gila. The chief offenders, of course, were the warlike Apaches…” (70)

Fighting between the Apaches and the Spaniards intensified such that by about 1710 the northern limit of Spanish settlement stood only at Janos and Fronteras, locations south of the modern international boundary between Mexico and the United States. Spicer wrote, “The few Spanish ranches and mining settlements which had existed north of this line were abandoned… A strip of territory nearly 250 miles wide, roughly from Casas Grandes to Zuni, now separated the Sonora-Chihuahua part of the frontier from the New Mexico part – an area in which there were no Spanish settlements and no semblance of Spanish domination and control.” (71) Within this gap is what Spicer called the “Apache Corridor.” (72) He wrote that “this strip of territory was not passable for Spaniards except with full military escort, and sometimes not even then.” (73) As for the “few Spanish ranches” that had “existed north of this line,” neither Spicer, nor any other reference found during my research, could point to where these were located. Significantly, early ranchers would not likely have selected the location of Kuykendall Ruins because other spots were much more attractive. Wagoner suggested that there were no ranches. “After Kino’s death in 1711 there is no record of a Spaniard having entered Arizona for twenty years.” (74)

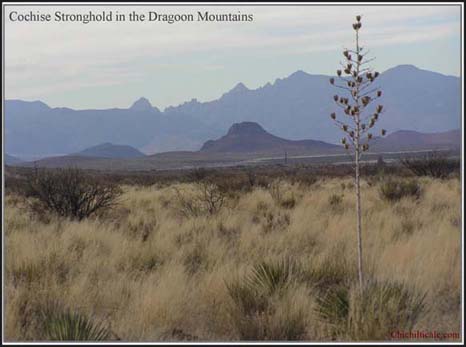

The Spaniards made few earnest attempts during the first seventy-five years of the 1700’s to gain control of the 250-mile gap. Historian Donald T. Garate mentions one of these efforts. In January 1721, Juan Bautista de Anza, lieutenant of Sonora, accompanied a group of citizen militiamen, Opata Indians, plus three or four soldiers, on a campaign against the Apaches. The group rode north from Bacoachi with pack mules and provisions in tow. “Beyond this, nothing is known of the campaign… It very likely went into what is today the state of Arizona and possibly into the mountains known as the Chiricahuas. Certainly many operations after this one were staged against the Apache stronghold in the Chiricahuas. Those later campaigns, generally led by trained military officers, often have detailed diaries recording what took place on a daily basis.” (75) Lack of success provoked a change in policy such that Spanish military actions by the offensively-oriented Flying Companies (Compañias Volantes) were reduced in 1724 to the extent that only defensive operations were conducted; this served to remove Spanish presence altogether in the land north of the modern international border. The Apaches reacted by increasing their raids as far south as central Sonora. The Spaniards responded by establishing the presidio at Terrenate at the headwaters of the Río San Pedro in 1741, but Apache success continued. In 1751 the Pima Rebellion was added to Spanish problems, forcing them in 1752 to establish a presidio at Tubac on the Río Santa Cruz. The Spanish military effort continued, but without fruition. Although there may be no written evidence for a Spanish presence at Kuykendall Ruins during the period 1542 - 1750, we found a copper military button dated 1710 – 1750. If the button arrived at the site with a Spaniard rather than a Native American, it suggests that at least one Spanish excursion visited the location during that two hundred eight year time span. (76) By the early 1760’s the Apaches had driven out the Sobaipuri living along the Río San Pedro, thereby adding the Río San Pedro Valley to Apache dominion. Historian and editor Peter Aleshire described the eighteenth century setting of southeastern Arizona. “The camps of the People (Apache) moved often, and the Spanish could not come into their country without the word going out for a long time before they arrived. Still, the fight went on for whole lifetimes. The Spanish built great walled forts in the most important towns and kept soldiers posted in them, but the warriors of the People moved about freely between the presidios. [On May 1, 1782] six hundred warriors gathered together to attack Tucson, taking all of the horses and burning the houses and the crops outside of the walled presidio where the soldiers hid.” (77) Violence continued into 1784. Cochise biographer and western historian Edwin R. Sweeney wrote that “Two years [after the attack on Tucson] a Spanish force surprised a band of Chokonens (Chiricahua Apaches) at Dos Cabezas, killing nine men, three women, and four children and recapturing a Pima woman taken in the attack on Tucson.” (78)

Apache rule continued unchecked until 1786 when the Spaniards initiated a policy of making peace treaties with individual bands of Indians. According to Wagoner, “This new policy was successful. At least there were no serious depredations until after the first decade of the nineteenth century.” (79) Sweeney suggested that the peace might have lasted longer: “Most historians agree that peaceful relations continued for the remainder of the Spanish period, that is, until 1821, and there is evidence to conclude that it prevailed until 1830” (80) Ethno-historian Bernard L. Fontana provided information suggesting that commerce improved during this lull in hostilities. “Alberto Suarez, my Sonoran historian friend, tells me there was a late 18th-century merchant in Arizpe named Esteban Gach who traded regularly with New Mexico. That line of communication certainly implies the establishment of a communication network between those two points.” (81) This implication is further supported by anthropologist Jack S. Williams, who told me that at Tubac there are late eighteenth-century artifacts from Zuni. (82) Spicer wrote that between 1786 and 1811 “Spanish mines and ranches began to appear again in depopulated Sonora and southern Arizona.” (83) Sweeney reported on commerce of that time: “It was during these years of respite that mines were opened and successfully operated, churches built and beautified, and ranches prosperously conducted.” (84) There is no record, however, that this peace-inspired reappearance of mines and ranches included Spaniards in the Sulphur Springs Valley, or, more importantly, at Kuykendall Ruins. Such appearances at Kuykendall Ruins were unlikely because of the lack of mines and the less preferable ranching conditions there. Moreover, these ruins rest at the foot of the Chiricahua Mountains at Apache Pass, the stronghold of the Chiricahua Apaches, and it is unlikely that these Indians would allow settlers or military encampments so near.

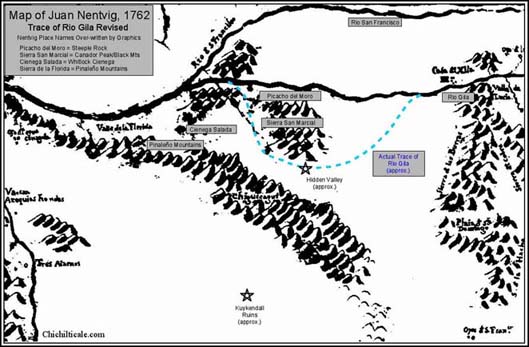

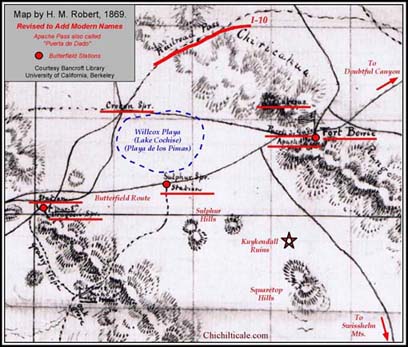

The 1788 military expedition of Don Manuel de Echeagaray, captain of the presidio of Santa Cruz, offers evidence that the Chiricahua Mountain region of the Sulphur Springs Valley remained dangerous and unsettled even after the policy change of 1786. Historian George P. Hammond defined the activities of Echeagaray as “a movement to establish a direct trade route between the province of Sonora and Santa Fé, the capital of New Mexico. The object was to open a route which would facilitate the exchange of goods between these two provinces to their mutual benefit, for it would be much shorter than the road by way of El Paso.” (85) Hammond recognized that the trail held danger: “And we must not overlook the fact that this proposed trade route lay right through the heart of the Apache country. What a problem that offered the Spaniards, for these mountaineers had always been their enemy.” (86) For his description of the Echeagaray adventure, Hammond did not present a map, and being that a map is essential to trace the trail of the Spanish horsemen, I used the 1762 map of Juan Nentvig. (87)

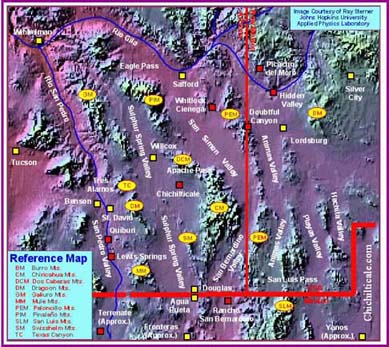

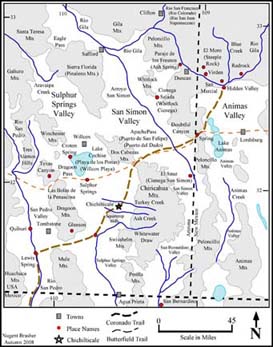

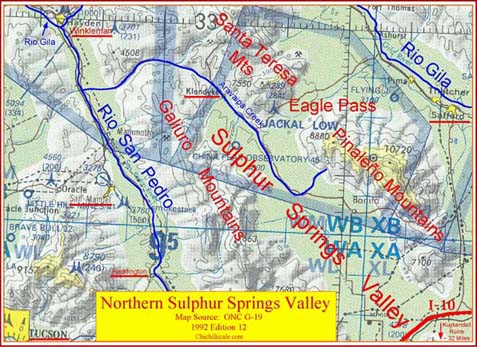

Hammond did not suggest a unique point of departure of the expedition in late September 1788, rather he wrote that men from Bacoachi, Bavispe, Buenavista, Janos, San Buenaventura, Altar, and Pitíc formed various companies that “were to unite at some point along the Gila River.” (88) The spatial array of these locations shows that in order to reach the Río Gila, the men had to cross one or all of the valleys of Sulphur Springs, San Simón, San Bernardino, and Ánimas. I have created a map intended to aid the reader in navigating this territory.

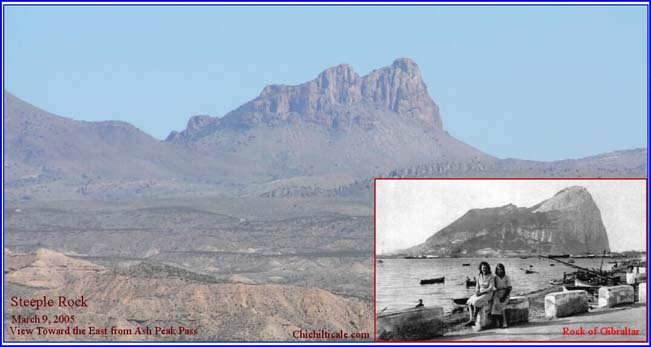

Hammond began the travel account of Echeagaray by noting that the Spanish officer wrote a letter on 1 October 1788 from San Marcial reporting a battle with Apaches in the Sierra de la Florida. Nentvig located the Sierra Florida as west of Ciénega Salada; I interpret these as, respectively, the Pinaleño Mountains and Whitlock Cienega. Nentvig placed the Sierra San Marcial south of Picacho del Moro. I interpret Picacho del Moro to mean Picacho of the Moor, so named by the Spaniards because of its shape closely resembling the Rock of Gibraltar, the imposing massif that faces the Moors from the Iberian Peninsula. Such a landform is obviously Steeple Rock near Duncan, Arizona, which I confidently identify as Picacho del Moro.

Given this interpretation, the Sierra San Marcial is likely a combination of Canador Peak and the Black Mountains, located just west of Blue Creek on the north bank of the Río Gila opposite Hidden Valley between Virden and Red Rock, New Mexico. Hidden Valley offers the most comfortable, spacious campsite along this stretch of the Río Gila, and provides protection on all sides by sheer-walled box canyons. My map interpretation recognizes that Nentvig incorrectly traced the Río Gila as it flows west from his Casa de Xila. He failed to turn the river to the south to create its remarkable half-circle bend to pass around the south side of his Sierra San Marcial before turning back north to its junction with the Río San Francisco near present Clifton, Arizona. Notably, Nentvig omitted the Peloncillo Mountains, the north-south trending range along the present-day Arizona-New Mexico state line. The effect of this omission is that the San Simón Valley is unconfined on his map. Of importance here is to show that in order to reach the San Marcial location, Echeagaray and his various companies of men must have passed one or both sides of the Chiricahua Mountains, thereby exhibiting the likely presence of Spaniards in the Sulphur Springs Valley in 1788.

Echeagaray may not have been the first Spaniard to visit Hidden Valley. I consider Hidden Valley to be the famous Río San Juan campsite of Captain General Francisco Vázquez de Coronado on the night of 24 June 1540. (89)

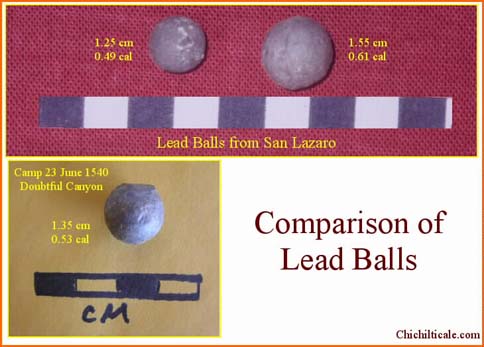

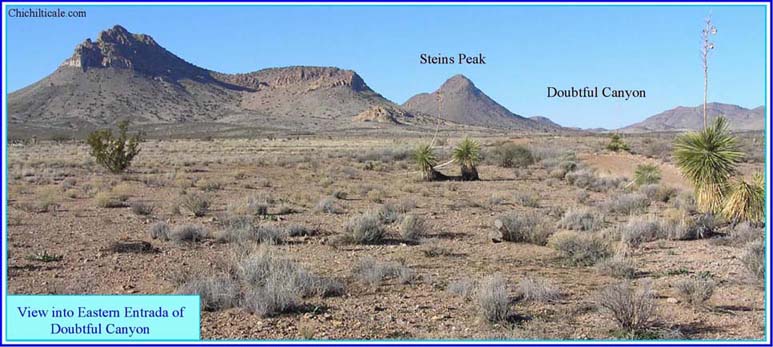

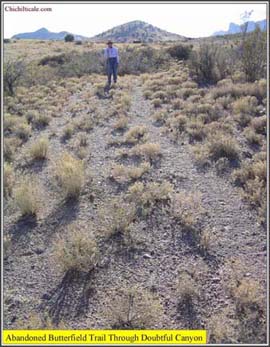

I interpret that Coronado reached Hidden Valley from Chichilticale (Kuykendall Ruins) by way of Doubtful Canyon, where he spent the night of 23 June 1540. Our February – March 2005 exploration of a private ranch in Doubtful Canyon resulted in finding a lead ball. Fig 29 shows this ball compared to lead balls found at San Lázaro and photographed by Richard Flint. We are currently holding in abeyance further exploration at Doubtful Canyon because of our activities at Kuykendall Ruins.

For the purpose of this narrative, only the Echeagaray events affecting the Chiricahua Mountain region will be reported. On 4 October, Echeagaray dispatched from San Marcial a report “carried by fast messenger to Bacoachi.” (90) This rider almost certainly passed through the Sulphur Springs or San Simón-San Bernardino valleys, with the latter being most likely. “On October 17 Lt. Don Narcisco Tapia arrived at the camp on the Gila with Division 2, composed of 151 men.” (91) Being as I interpret that this camp was on the Río Gila at Hidden Valley, it is probable that the route traveled by Division 2 included the Chiricahua Mountain region, most likely the San Simón-San Bernardino valleys. Soon thereafter, “Lt. Manuel de Albizu was sent to Fronteras with most of the prisoners.” (92) Albizu in all likelihood traveled through the Chiricahua Mountain region, with the San Simón-San Bernardino route most probable. By 19 November Echeagaray was in San Bernardino on his return. This fact alone suggests that the preferred route from the stretch of the Río Gila visited by the Spaniards was through the San Simón-San Bernardino valleys. Lt. Albizu had left 13 November to go “down the Gila on a reconnaissance.” (93) This means that the lieutenant traveled west along the Río Gila, and that he had to turn south to return to Sonora, thereby crossing either the Sulphur Springs or San Simón valley. Also during the return south, “Ensign Don Nicolás Leiva, setting out from San Simón with a smaller force of 58 men, explored the Chiricahua Mountains, but he found no trace of hostile Apaches.” (94) Again, the fact that the ensign left San Simón shows that the eastern side of the Chiricahuas was the favored route. While the combination of these excursions suggests that the Spanish military expedition of Echeagaray might have touched the Sulphur Springs Valley, the greater likelihood is that the San Simón-San Bernardino valleys were where Echeagaray traveled. There is no direct evidence that the soldiers ever traversed Apache Pass or visited Kuykendall Ruins.

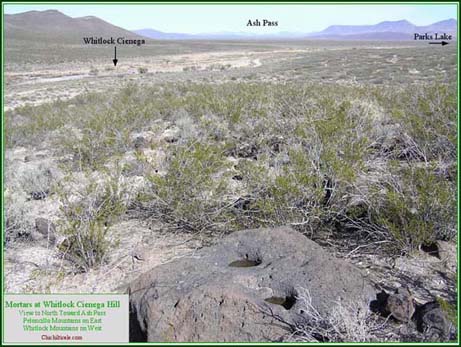

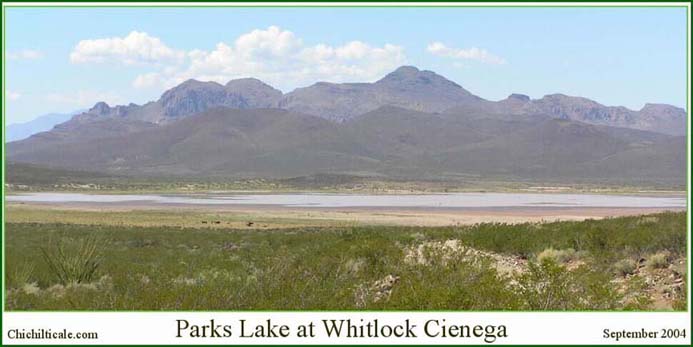

Echeagaray failed to reach Zuni. Hammond reported that “During the next few years the officials in Arizpe and Mexico City often pushed new plans for the opening of the western route to Santa Fé.” (95) However, from 1791 to 1795 “trouble with the Apaches was incessant. In 1795, at length, the project was carried through.” (96) The leader of the expedition was Don Joseph de Zúñiga, captain of the Tucson presidio. Editor Amando Represa reproduced the Zúñiga diario (journal) in its original Spanish and I used it as my source. (97) Zúñiga departed Tucson on 9 April 1795 “with the troop of this company,” spent the night at la Ciénaga de los Pimas, and arrived at the abandoned presidio of Santa Cruz on the 10th “where he found the parties of his expedition.” (98) The group totaled one hundred fifty-one. On the 12th Zúñiga with one hundred men marched to their camp at las Bolas de la Peñascosa. I interpret these “rocky balls” to be Texas Canyon, Arizona. By the end of the day on the 13th, Zúñiga had reached Santa Teresa springs after having searched “la Peñascosa, Cabezas, y Playa de los Pimas.” (99) I interpret these places as Texas Canyon, the Dos Cabezas Mountains, and Lake Cochise (Willcox Playa). The route was to the northeast, and likely included Croton Springs on the northwest side of Lake Cochise; Santa Teresa springs were probably on the north end of the Dos Cabezas Mountains. The following day the troops searched la Florida, (Pinaleño Mountains) and that night the fifty-one men who had remained at Santa Cruz joined Zúñiga. On 15 April Zúñiga marched across the San Simón Valley to Ciénaga Salada (Whitlock Cienega) and “made stop at their springs.” (100) The next day he headed north. My interpretation shows that Zúñiga did not visit Kuykendall Ruins – his route carried him well to the north.

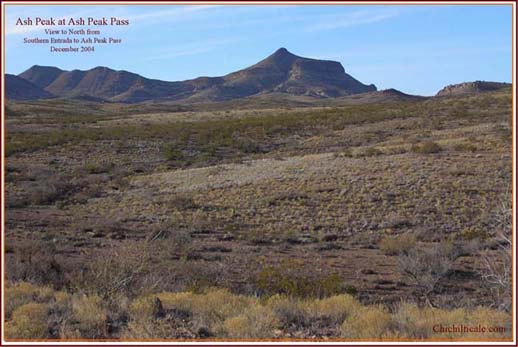

The Zúñiga return to Tucson traced much of the route of his entrada, but some variations are notable. On the night of 22 May Zúñiga and his men camped at “the rest stop of the Ash Trees” (Ash Spring).

The next day the Spaniards headed south through Ash Pass and arrived at Whitlock Cienega the afternoon of 23 May 1795.

The following morning Zúñiga dispatched two patrols – one to la Sierra de las Cabezas y Chiricagui, the other to San Marcial, San Simón and Los Almireses. The patrols were to search for three missing mules. Two days later, on 26 May, both patrols reunited with Zúñiga at the south end of the Pinaleño Mountains. The patrol that had searched the Dos Cabezas and Chiricahua mountains reported not finding a single track in those places. The other patrol had found tracks and had followed them “as far as Puerto del Dado, concluding that [the mules] went to Fronteras because one of the mules was from that presidio and [knew the way back because] on another campaign it had made the return [to Fronteras] from the Río Gila.” (101) On 27 May the expedition split into two groups, one traveling to the Río San Pedro, the other to Tres Alamos. Puerto del Dado means Dice Pass, an appellation implying that safe passage depended on the roll of the dice. This spot is Apache Pass. It is notable that the name San Felipe given this same pass by Juan Fernández de la Fuente in 1695, exactly one hundred years before, had been abandoned in favor of a more colorful moniker. With respect to Kuykendall Ruins, there is no evidence that members of the returning Zúñiga expedition visited the site. The patrol that followed the mule tracks to Apache Pass was in the San Simón Valley. If the patrol that went into the Dos Cabezas and Chiricahua mountains got as far south as Kuykendall Ruins, Zúñiga did not report it.

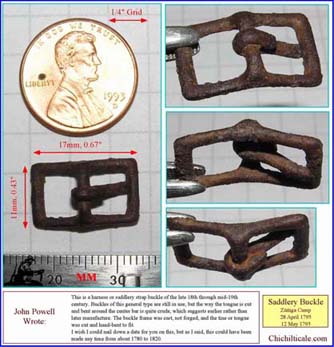

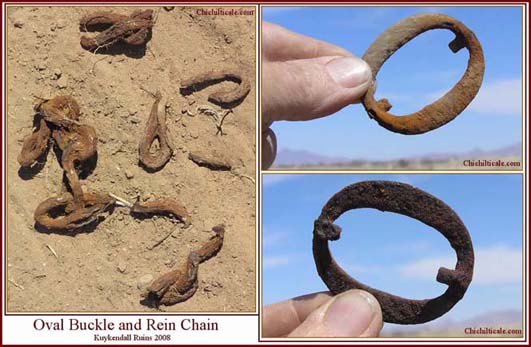

Of interest is that the Spaniards suspected that the mules knew the way through Apache Pass to Fronteras. This is compelling evidence that late eighteenth-century Spaniards from Fronteras traveled through Apache Pass. Moreover, being that Kuykendall Ruins are on a direct line connecting Fronteras and Apache Pass, it is very likely that Spaniards visited the ruins. Evidence that the trail was long-lived comes in the form of an 1879 map prepared under the direction of 1st Lt. Fred A. Smith, Adjunct 12th Infantry. The map shows Fronteras Road connecting Fort Bowie and Apache Pass with Fronteras. Geographer Conrad J. Bahre provided me a photograph from the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkekey of the 1869 map of southern Arizona made by H. M. Robert. This graphic also shows a trail along the western side of the Chiricahua Mountains that is likely a portion of the Fronteras Road. (102) Fronteras Road as traced on the map passes three miles east of Kuykendall Ruins. Recall that we discovered at Kuykendall Ruins a 1710 – 1750 copper military button, a 1774 Spanish coin, and a 1780 – 1820 oval buckle and associated rein chain. Now come the 1795 mules. As we shall learn, these five pieces of evidence offer the only indications of Spaniards at Kuykendall Ruins after Coronado in 1542.

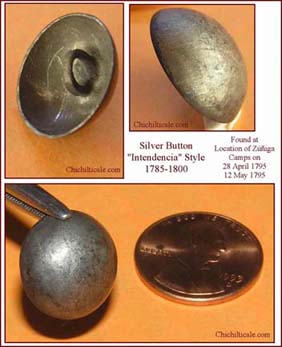

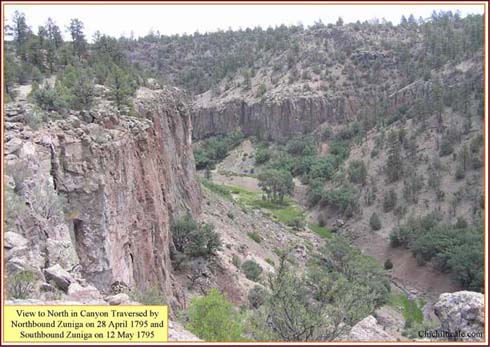

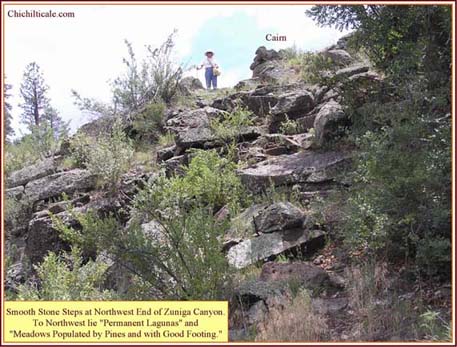

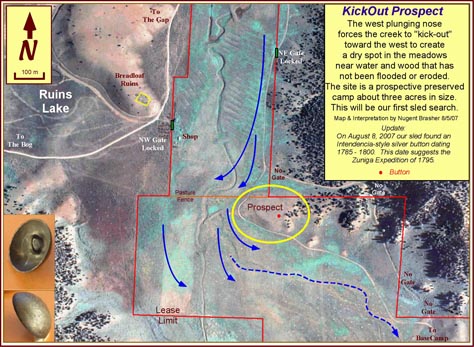

The Zúñiga expedition reached Zuni, accomplishing the Spanish objective of blazing a trail from Sonora to Santa Fe. I have interpreted the entire route of Zúñiga and I find that much of it follows the route I believe to be that of Coronado. During the summer of 2007, we explored a private ranch looking for metal artifacts of both Zúñiga and Coronado. We found a silver button and an iron harness or saddlery strap buckle. Spanish button and buckle expert John Powell dated these, respectively, as 1785 – 1800, and 1780 – 1820. (103) This tight range of dates falls within the time Zúñiga explored for the New Mexico Road.

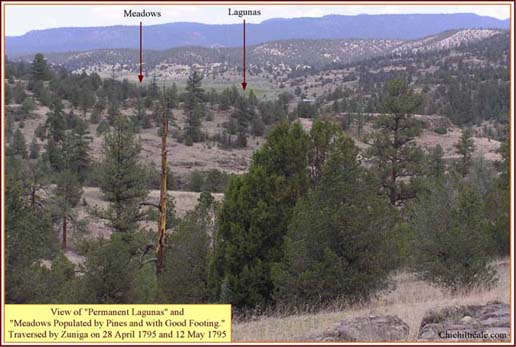

The site of my summer 2007 exploration represents the place so accurately described by Zúñiga on 28 April 1795 and again on 12 May 1795: “After about a quarter of a league we left the canyon, laboring to the north-northwest. There are found some permanent lagunas that show themselves, and heading to the north, we walked through various meadows populated by pines and of good footing.”

I interpret that this same spot served as the camp of the advance party of the Coronado Expedition on 2 July 1540, of his following army on 4 October 1540, and of his retreating army on 8 April 1542. (104) Our exploration continues at this place, so I will not reveal its location at this time. I find it remarkable that Zúñiga, hoping to find the Camino del Nuevo México, may well have found the very trail followed by Capt. Gen. Vázquez de Coronado to Zuni; if so, then the trail is once again shown to be old and well traveled.

The successful adventure of Zúñiga did not lessen the Apache threat in the Sulphur Springs Valley. Southwest historian James E. Officer pointed out that “enough [Apaches] remained hostile to prevent much use of the trail blazed by Zúñiga and his soldiers.” (105) At the end of 1811 disorder increased because of the disruption of government in Mexico preceding the 1821 Independence. This provided an opportunity for the Apaches to mount increasingly bold outbreaks of violence. Spicer wrote, “Between 1820 and 1835, five thousand Mexicans were killed by Indians on the northern frontier and four thousand others were forced to leave the area. Northern Sonora regressed again to the state it had been in before 1786.” (106) Although land grants in southeastern Arizona increased beginning in 1820, these grants did not result in occupation of the Sulphur Springs Valley. The 1820 San Bernardino grant included only a tiny portion of what is now the San Bernardino Valley east of present Douglas, Arizona. According to J. J. Wagoner, in applying for the San Bernardino grant, the grantee “stated that it was his intention to create a buffer state against the Apaches.” (107) I interpret this to mean that the grantee hoped to contain them north of his ranch, that is, in the Sulphur Springs and San Bernardino valleys. The 1827 San Rafael del Valle and San Juan de las Boquillas y Nogales grants were located on the Río San Pedro south of old Quíburi. (108) Officer related that “Because of the Apache threat, however, they were able to live on their ranches for no more than a dozen years.” (109) Cattle historian Bert Haskett wrote that “from 1822 to 1872 includes the time when the Apache depredations were at their height and ranching operations were at a standstill.” (110) Wagoner reported that the “San Bernardino was abandoned in the 1830’s.” (111) Officer summed up the early departure of the ranchers: “The grantees had ceased to reside on their ranches by 1840. Exactly when they moved… is unknown, but according to testimony… in the 1880s, it occurred quite early for some.” (112) There is no evidence of any land grantee ranching presence at or near Kuykendall Ruins. History suggests the likelihood that the aforementioned 1774 Spanish coin, the 1780 – 1820 oval buckle, and the associated rein chain were dropped at the ruins, if by Spaniards, during the lull, if one can comfortably believe there was such, between 1786 and 1811. Of course, the objects could also have arrived at the site with Native Americans.

Leonardo Escalante, acting governor of the state of Sonora in 1831, received authorization to “stimulate occupation and development” of a large block of land that extended from old Quíburi north to the Río Gila and as far east as the modern Arizona – New Mexico state line. This became known as the Tres Alamos grant (113) The Apaches immediately prevented the proposed development. By July 1834 the situation had worsened to include a warning issued by a peaceful Apache woman that the Apaches “living in the Chiricahua Mountains” were planning an attack on Tucson and Tubac. (114) A military campaign headed by Manuel Escalante y Arvizu was organized to respond to the threat. Escalante y Arvizu stationed his headquarters on Babocómari Creek east of the Río San Pedro. James Officer wrote, “On September 27th [Escalante y Arvizu] sent a detachment of men into the field with instructions to remain there, harrying the Apaches for twenty-four days. The detachment included six companies of cavalry and infantry – a total of 442 men. The governor stayed behind with a small force of 100 men, guarding 200 loads of provisions and 1,800 horses. His plan was to move the supplies and the herd to Willcox Playa (then known as La Playa de los Pimas), and from there to San Simón.” (115) Shortly thereafter, “Escalante [y Arvizu] dispatched a second detachment against the Apaches. This one had the Mogollon Mountains of New Mexico as its ultimate destination. They proceeded generally along the route followed in modern times by the highway between Willcox and Lordsburg, New Mexico. The strategy was to surprise the Indians of the Mogollon area… They were detected, however, and unable to gain the major victory that had hoped to achieve. They did capture Tutijé (the Apache leader).” (116) The Escalante y Arvizu campaign demonstrates that Mexican soldiers were present in the Sulphur Springs Valley in the fall of 1834. Historian Edwin R. Sweeney provided some additional details of the Escalante y Arvizu campaign. “Guided by several Opata Indians and seven tame Apaches enlisted from Tucson, the detachment reached Puerto del Dado (Apache Pass) on October 15…. To this point the command had found thirteen rancherías, abandoned since the previous summer. Three were discovered in the Chiricahua Mountains and two at Apache Pass, one near the springs and the other in the canyon… From Apache Pass the command followed an Indian trail north. On October 24 in the foothills of the Mogollons they surprised hostiles returning from a foray into Chihuahua.” (117) Tutijé was captured. The place names mentioned in the account provided by James Officer all lie north of Kuykendall Ruins. As for the detachment of 442 men, it is possible that these troops visited the ruins, but it is unlikely that they camped there because by 1834 Turkey Creek had captured the water flow from Ruins Arroyo, leaving that former stream at Kuykendall Ruins abandoned, dry and unattractive as a camp site.

James Officer concluded that “the great offensive of 1834… ended with relatively little accomplished.” (118) Although the Apache terror remained unchecked, by 1845 the Mexicans found themselves unable to even consider confronting their enemy. According to Officer, “The soldiers were further handicapped because the combined garrisons of Fronteras, Tucson, and Santa Cruz had fewer than 200 horses (for nearly 250 men) and none of those could stand up to a journey of more than ten leagues.” (119) Officer also wrote that an excursion along the northern stretch of the Río San Pedro had caused Antonio Comandurán, commanding officer at Tucson, to lament “the miserable situation of the cavalry,” and he revealed that his “garrison was limited to defensive measures because of the lack of horses… and were nearly out of provisions and had no money…” (120) Spicer summed up the situation at the beginning of the 1850s: “Apache raiding extended more widely than it ever had before. Not only was central Sonora raided repeatedly along with eastern Sonora, but now the raids extended to Tucson and even west of the Santa Cruz River well into the country of the Papagos. The Mexicans seemed powerless, as had the Spanish before them, to devise any lasting means for bringing about peace on the margins of the Apache territory. This was the situation when the Anglo-Americans took over control of southern Arizona in 1853.” (121) Given these circumstances, it is reasonable to assume that the Anglo-Americans found no Hispanic settlers in the Sulphur Springs Valley, and certainly not at Kuykendall Ruins.

Prior to 1853, few Anglo-Americans visited the Sulphur Springs Valley. One of the earliest written accounts is that of beaver trapper James Ohio Pattie. I interpret his narrative to show that on 25 March 1825 Pattie and his party were at modern Winkelman at the junction of the Río Gila and the Río San Pedro, which he called, respectfully, the Helay River and the Beaver River. They headed upstream on the Beaver, and that afternoon and the following morning, the party prevailed in a battle with Indians armed with bows and arrows. The party continued upstream to a camp by the river on the night of 29 March. The following morning they began their ascent of the Galiuro Mountains, reaching the top on 31 March, where they consumed their last beaver meat. Pattie and company began their descent on 1 April, and reached a plain the next afternoon. They killed one of many antelope and appropriately named the location Antelope Plain. This was at the north end of the Sulphur Springs Valley near the head of Aravaipa Creek. By the afternoon of 3 April the party had crossed the narrow north end of the valley and started their ascent of the Pinaleño Mountains. On 12 April 1825 the seven-man party reached the Helay River. (122) The portion of the Sulphur Springs Valley visited by Pattie is about sixty-five miles northwest of Kuykendall Ruins.

Spicer mentioned trappers. “By the 1820’s trappers… had established something of a headquarters at Taos… About one hundred trappers obtained licenses from Santa Fe Mexican officials in 1926 to trap along the Gila River; in pursuing their trapping they came into contact with Apaches… By 1837 the beavers had been trapped out of the Gila, the fur trade was in decline, and Anglo contacts with Apaches ceased.” (123) It is probable that very few beaver trappers ventured into the Sulphur Springs Valley, especially to the dry, remote region around Kuykendall Ruins.

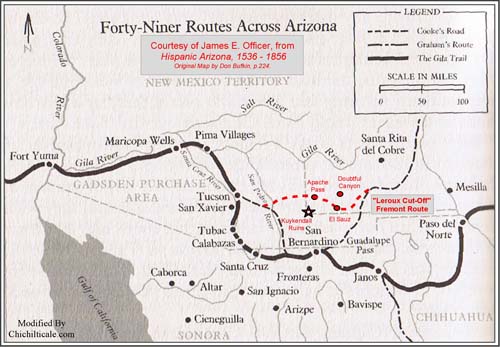

The Apache threat at the Chiricahua Mountains did not prevent a group of Americans from entering Sulphur Springs Valley in 1831. Carl D. W. Hays recounted the travels of mountain man David Jackson, who led a party of eleven men from Santa Fe to California. “Each man had a riding mule; there were seven pack mules [and] five of the pack mules were loaded with Mexican silver dollars… [From the Santa Rita copper mines] the route led southwest over the old Janos Trail as far as the Ojo de Vaca in the northwest corner of present Luna County, New Mexico. Colonel Philip St. George Cooke and the Mormon Battalion later followed that part of the route in 1846. From Cow Springs to the abandoned mission of San Xavier del Bac [Tucson], David Jackson’s party was opening a new direct route between New Mexico and Arizona. Their route preceded from water hole to water hole by way of Doubtful Canyon, Apache Pass, and Dragoon Wash to the San Pedro River just north of present St. David, Arizona… This direct route had been traversed in sections over its complete length by various Spanish and Mexican military parties under military members of the Elias-Gonzales family on account of Indian hostilities. After Jackson opened that route there is no record of its having been used again until the Fremont Association party passed over it with minor deviations in October and early November, 1849. Jackson’s party should have reached Tucson by early October, 1831. Jackson must have been one of the first American citizens to have ever seen the mission of San Xavier and the old walled pueblo of Tucson. He may have been the first.” (124) The Jackson party represents the first Americans so far south in the Sulphur Springs Valley. However, it is likely that the Jackson party passed well to the north of Kuykendall Ruins.

War between the United States and Mexico began in May 1846. This brought the Mormon Battalion headed by Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke to the Sulphur Springs Valley region. The battalion entered modern Arizona from New Mexico through Guadalupe Pass located near the common corners of New Mexico, Arizona and modern Sonora. On 2 December 1846 Cooke “crossed wide meadows to the old houses of the rancho of San Bernardino; it is enclosed by a wall with two regular bastions; the spring is fifteen paces in diameter.” Cooke left San Bernardino on 4 December and headed west, reaching the Río San Pedro on the 9th. His map shows the trace as along the present-day international border. The Cooke route, therefore, was south of Kuykendall Ruins and the Sulphur Springs Valley. (125) Following behind Cooke two years later came Maj. Lawrence P. Graham. 1st Lt. Cave Johnson Couts of the First United States Dragoons kept the record of this expedition. The expedition left Janos 26 September 1848. “From Janas [Janos] we launched into the mountains and plains without a sign of a road or trail.” The group had found two Mexicans to guide them, but these men “had not been on the route for many years.” Couts wrote, “We are making our own road as we go, and quite a trail we leave, too.” By 5 October the group had struggled to the deserted ranch at San Bernardino. Their route had taken them through a cañada requiring five hard days to traverse because of flash floods. The next day the expedition marched to Agua Prieta to a dry camp selected by the habitually inebriated Graham. Unknown to the major, some men located “a small lake of water sufficient for thousands upon thousands to encamp.” Graham prevented his party from using the water. This dry camp was as close as the expedition came to Kuykendall Ruins, which lay about forty miles almost due north. The next day the travelers happened upon “a few pools” of water and camped. Moving ahead they reached “Sauz or Sauce” and found “good water and grazing.” Afterwards they “struck the headwaters of the San Pedro river.” Graham ordered his party to disregard Cooke Road, which followed the river downstream to the north, instead opting to go west. The party became lost and was forced to “send to this place St. Cruz for a guide to get us out of the mountains.” Graham and party arrived at Santa Cruz on 14 October 1848. (126) The map provided by Couts shows the expedition skirting the south end of the Huachuca Mountains to reach the Río Santa Cruz. This alternative to the Cooke Road became the Gila Trail. (127) Obviously, the Gila Trail did not pass through Kuykendall Ruins.

News of the gold discovery in California reached the east coast of the United States in August 1848, but many considered it rumor. After President James K. Polk confirmed the discovery on 5 December 1848, the westward rush began. James Officer wrote, “The first known civilian group bound for California to pass through Arizona was a party headed by John C. Fremont. They reached the area during March.” (128) Historian Allan Nevins provided the account of the journey as reported by Fremont himself in “his usual crisp English:” “With 25 men all told and outfit renewed I resume journey… intending to reach the Río Grande by a route south of Gila River. The snows this season too heavy to insist on a direct route through the mountains. Engage a New Mexican for guide… Retreat into the Membres [Mimbres] Mountains… Travel along foot of mountains… Apaches around the camp… Make friends. The Indians go to Membres River with us… Indians direct us to watering place in the open country – appoint to meet us there – their war parties out in Chihuahua and Sonora. I push forward and avoid them. The Apache visitor – Santa Cruz. The Mexican and the bunch of grass. Follow down the Santa Cruz River – Tucson.” (129) The Fremont account suggests that the party of twenty-five followed the Gila Trail to Santa Cruz and Tucson, thereby passing south of Kuykendall Ruins.

Officer reported that following Fremont came a flood of travelers. (130) For the sake of providing a few accounts, I will offer those below. (My list is highly selective, as any reader can ascertain by consulting the bibliography of accounts by those following southern routes compiled by Patricia A. Etter, To California on the Southern Route, 1849: A History and Annotated Bibliography. Spokane, Washington, The Arthur H. Clark Company.)

Young Harvey Wood of New York state joined the Kit Carson Association and traveled to California via Tucson. His brief account reveals that he departed Chihuahua (City) on 8 May 1849 and “passed through [country] almost barren of game,” eventually arriving at “Yauos” [Janos], where six Apaches “were amusing themselves by riding from store to store and making the proprietors furnish liquor… From Yaous to Tucson we found several villages completely deserted, caused by Apaches making a raid on the place.” Wood provided a map that shows that he traveled from Janos to San Bernardino to Santa Cruz. (131)

Asa Bement Clarke kept a daily journal of his travels to the California gold fields. He departed Janos on 13 May 1849 with a party from Missouri, writing, “We take Graham’s route.” (132) Two days later the party reached the foot of some mountains and climbed to the summit. “We looked down upon an extensive valley, luxuriant with grass, and studded with hillocks, with mountains of different heights at its circumference. At our feet lay a beautiful little lake, sparkling in the sun. We descended [into] the valley and camped among the fine grass, near a spring of cold water.” (133) I interpret this event to be the crossing of the San Luis Mountains in contemporary New Mexico and dropping into the Animas Valley on the present-day Gray Ranch in Hidalgo County, New Mexico. The little lake was Lake Cloverdale. On 17 May the travelers began their struggle through Guadalupe Pass, eventually reaching the San Bernardino Valley the afternoon of the 19th. “On a bluff at the edge of the bottom [of the valley] is an old deserted rancho, which has the appearance of having once been extensive. We camped at this place… Starting at sunrise [the next morning] we passed the extensive ruins of the rancho Santa Bernardino, the walls of which are fortified with regular bastions… Passing over a mountain, at a place where the passage was not difficult, we came in view of another valley fifteen or eighteen miles across.” (134) I interpret this wide basin to be the Sulphur Springs Valley. The party continued west along the Graham route, eventually reaching Santa Cruz the evening of 24 May 1849.

William W. Hunter left Montgomery County, Missouri on 23 April 1849, “for a journey to California.” (135) On 8 September his party passed by “Ojo de Verra (Cow Spring) and near it crossed the Ganos (Janos) road to the Copper mines N. of this.” (136) The travelers were attempting to follow the Cooke Road. By the 14th the party had reached “where the Ganos road enters from the Eastward, [and] now commenced our traverse of the Guadalope [Guadalupe] Pass.” (137) Hunter and his fellows reached “the Deserted Rancho of San Bernardino early in the evening” of 16 September. “The walls of most of the buildings on this Rancho are yet standing… At this Rancho there are the remains of an old furnace, which from appearances, must have been considerably used for the purpose of smelting ore.” (138)

Hunter described the road westbound from San Bernardino as “excellent,” and by 20 September the party reached Blackwater Creek (Agua Prieta), and on 22 September arrived at a camp south of present Naco, Arizona. (139) That evening “a Mexican who represented himself to be a lieutenant stationed at a mountain within 12 miles of here, came into camp. He spoke English more fluently than any Spaniard I had ever heard, stating that he had received his education in England. He informed us that there are now 800 men in this vicinity on their way into Apache Country…They will proceed to the Dry Lake in hopes of meeting a large band of Apaches reported to be now there. He states that Cook’s [Cooke’s] old trail is some distance North. This road having been made and traversed only this season.” (140) This officer was part of the counter-insurgency initiated by Mexican Col. José María Elías Gonzáles, and the Dry Lake mentioned is, of course, Lake Cochise (Willcox Playa). Hunter and his party continued west the next day, crossing the Río San Pedro and continuing to Santa Cruz.

The daily diary of goldseeker H. M. T. Powell shows that his party descended Guadalupe Pass the morning of 22 September 1849. Powell noted a “broad Indian Trail [trending] north to south.” (141) That evening the travelers camped “on a dry bluff about a quarter of a mile north of the rancho [San Bernardino], and got our water from a fine spring near it.” The following morning Powell would find a “furnace for melting ore.” (142) Powell wrote critically of Cooke that night. “The valley in which the Rancho is situated is a broken and uneven one… It is not an open Plain as I was led to suppose from Cooke’s slovenly report. The other party have killed 2 wild bulls. On looking back from here, to the East, the pass seems to go through the wildest and highest mountains in the range. Either North or South of it looks lower and better and I cannot but think a better trace could be found. The Leroux cut-off is the way and I believe it will soon be taken by all travelers.” (143) The next morning Powell sketched Rancho San Bernardino and described it in his diary before departing to the west. The travelers passed Black Water Creek (Agua Prieta) and the Río San Pedro before reaching Santa Cruz on 2 October 1849. Like the parties of Harvey Wood, Asa Bement Clarke, and William Hunter, the Powell group followed the Gila Trail, so none of these travelers visited Kuykendall Ruins.

By the middle of October 1849, Col. Elías Gonzáles, whose lieutenant had come in contact with the Hunter party south of Naco, had reached New Mexico. James Officer reported that the Mexican expedition was south of the Santa Rita mines, where they “encountered a group of Americans belonging to a party calling itself the Fremont Association. (144) Robert Eccleston kept a diary of the Fremont Association journey. At the camp on Sunday night, 14 October 1849, near the south end of the Burro Mountains of New Mexico, Eccleston reported that the guide “thinks it is from this camp that Colonel Cook [Cooke] recommends a cut-off from the road through a country in which we will, from all accounts, meet no difficulty. If water can be had, it will save over 100 miles travel.” (145) Consideration of this route likely resulted by the Fremont party consulting the Cooke map and seeing the trace labeled “Believed by Mr. Leroux to be an open prairie & a good route if water is found sufficient.” (146) The following morning a “party of Mexicans, numbering over 400” arrived at the Fremont camp. This permitted the Fremont leader to ask the Mexican “general about the route we desired to take. [The general] said it was much more direct and thought we would meet no obstacles, also find water. He sent for his sargent [sic], who he said had been through that way and offered him as a guide.” The next morning a “vote was taken and resulted in a large majority in favor of the new route.” On the morning of 17 October, “We followed the old road for half a mile and then left it, making an angle of about 35 degrees with it.” (147)

All of the forty-niners I have previously mentioned followed the Gila Trail, a portion of which led southwest from the south end of the Burro Mountains to the San Bernardino ranch, and then turned west toward Santa Cruz. The Fremont Association was the first recorded party to break from that preferred route. H. M. T. Powell had accurately predicted such would happen: “The Leroux cut-off is the way and I believe it will soon be taken by all travelers.” (148)

That portentous morning of the 17th, less than a month after Powell had forecast a soon-to-arrive route change, the Fremont party turned off the Cooke Road at the south end of the Burro Mountains and headed east toward Apache Pass, reaching water in San Simón Draw on the afternoon of 20 October. The next day they continued east across the San Simón Valley through thick chaparral toward a “point or gap.” Rough going slowed them from reaching Apache Pass until 24 October. “The road was tolerable good till we reached the pass, which was indeed a romantic one. We followed the bed of a dry arroya where there was scarcely room for the wagon wheels, let alone room for the driver. This road was overshadowed by handsome trees, among them I noticed the pecan, the ash, oak, willow, and etc. After leaving this part of the road, we came to a more open country, very hilly, many of which were very steep. We, however, came safely through and camped with the mule trail at a little stream, or a spring, gently flowing from the rocks or mountains… On the rolling country after we left the arroya, the mountain sides were beautifully studded with scrub oak. I also noticed cedar, the finest I have seen in some time.” The party rested through the next day. “We have excellent water here and the best grama grass is found on the hills, wood plenty and handy.”(149) Eccleston offered a perfect description of entering Siphon Canyon from the east and following the streambed to Apache Spring, which sits in small, grassy basin surrounded by steep mountainsides covered with oak and cedar.

The party left Apache Spring at noon on 26 October 1849. “The first two miles of the road was very bad, and like the other parts of the pass. After we left the mountains our road was still rolling. However, after getting on the plain, the road was beautiful, with the single exception that it was very dusty. There was a good deal of debate about what was supposed to be a large lake ahead; others affirmed it was sand, and some a fog.” (150) Eccleston nicely described leaving Apache Pass, rolling over the southwestern foothills of the Dos Cabezas Mountains, which offered a view to the west at Lake Cochise (Willcox Playa), and entering the flats on the eastern side of the Sulphur Springs Valley. Unknown to Eccleston was that Kuykendall Ruins lay about fifteen miles to the south.

After a dry camp that night, the party continued the morning of 27 October. “After travelling over a level plain we entered a great sand plain, level and smooth as a ballroom floor. We passed a small pond of water near the road, but it was so salt that the horses would not drink it.” The camp that night was where “The springs of fresh water boil up and lose themselves in the sand.” (151) The account of Eccleston reflects that the party crossed Lake Cochise (Willcox Playa) and arrived at the fresh water of Croton Springs on the northwest side of the vast playa. George P. Hammond helped edit the Eccleston version I consulted, and Hammond interpreted that from Croton Springs the Fremont Association traveled to Tres Alamos Draw and descended to the Río San Pedro. (152) Support for this interpretation is that Eccleston wrote that Colonel Cooke forded the river “some 10 or 15 miles above” where the Fremont party crossed. (153)

Colonel José María Elías Gonzáles was the “general” who provided the Fremont Association with a sergeant and guide. Recall that on 22 September 1849 at his camp south of Naco, Arizona, traveler William W. Hunter reported the arrival of “a Mexican who represented himself to be a lieutenant… [and] informed us that there are now 800 men in this vicinity on their way into Apache Country” (154) These Mexicans belonged to the expedition of Elías Gonzáles. Edwin Sweeney provided some details of the Elías Gonzáles campaign that followed. The offensive was “launched from Bacoachi on September 23, 1849. Dividing his force into three divisions, he took one force, which would enter present-day Cochise County, Arizona, and scouted the ranges of that area; Captain Agustín Moreno with 80 troops and the supply train would journey northeast and establish a base camp at Sarampion in the Peloncillos; José Terán y Tato took the third branch of 130 national troops, which would reconnoiter the mountains in northeast Sonora before going to Sarampion at the end of September.” (155) It might be that the English-speaking lieutenant was the officer unnamed by Sweeney who was leading the party into southwest Cochise County. Sweeney located Sarampión (measles) on the western side of the Peloncillo Mountains near Skeleton Canyon. The troops arrived at the Chiricahua Mountains in a driving rainstorm on 27 September 1849. Two days later they were in Apache Pass, but found no Indians. “Elías Gonzáles decided to suspend operations and join the supply train. He cut through Apache Pass and proceeded along the eastern face of the Chiricahuas, arriving at Sarampion on October 1. The pack train was nowhere in sight… At San Bernardino he met an American wagon train en route to California via Cooke’s route.” (156) From San Bernardino Elías Gonzáles forayed into Sonora before returning to the San Bernardino area, and then headed to the Burro Mountains, where he encountered the Fremont Association. From the Burros, Elías Gonzáles went to Janos, where he found no Apaches. This ended his campaign. There is no evidence that Elías Gonzáles ever visited Kuykendall Ruins, to the contrary, his movements suggest that he did not.

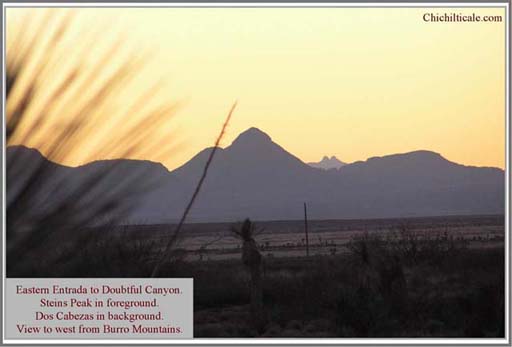

Following the Mexican-American War, on 2 February 1848, the treaty-makers at Guadalupe Hidalgo established the boundary between the United States and Mexico. The effort to effectuate the boundary led to the appearance in the Southwest of United States Land Commissioner John Russell Bartlett, who produced an illustrated account of his travels, which included duplicating a portion of the route traversed by the Fremont Association. Using this account, I interpret Bartlett to be camped at the foot of Sugar Loaf Hill (Stein’s Peak) in Doubtful Canyon the morning of 1 September 1851. That day he climbed into the hills on the north side of the canyon, where he was caught in a shower and took refuge in a “natural opening in the side of a rock.”

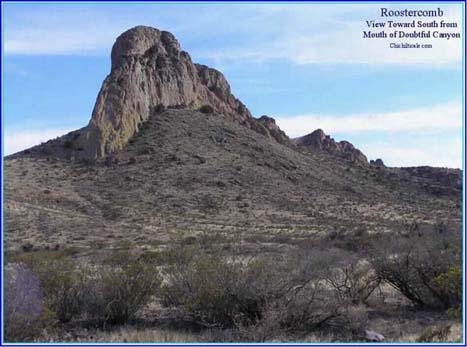

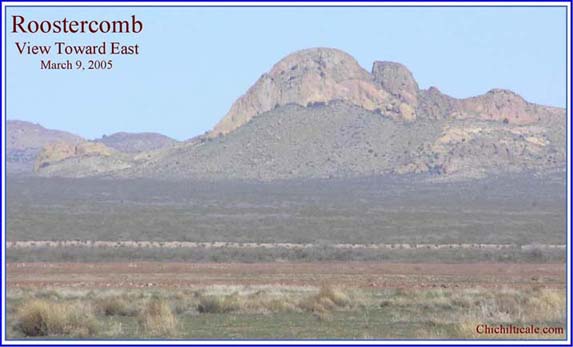

On 2 September 1851, Bartlett split his party in two, sending the wagons through modern Steins railroad pass while he and the pack mules followed Doubtful Canyon to its western side at the Rooster Comb. Once into the San Simón Valley, Bartlett continued to the spot that he called El Sauce, later called El Sauz and San Simón Cienega, where he camped. The next night he dry camped in the San Simón Valley. On 4 September the party entered Apache Pass through Siphon Canyon and found Apache Spring for a campsite. The next day Bartlett traveled through Apache Pass and into the Sulphur Springs Valley, working hard to reach a camp that night located a mile from Sulphur Springs. He rested two days, and on 8 September 1851, the party went through Dragoon railroad pass and found a camp on the Río San Pedro near St. David, Arizona. The route of Bartlett represents an east-west trail connecting water holes. (157) Kuykendall Ruins are not located on this trail.

Of interest respecting the Coronado Expedition is the Bartlett route south from his St. David, Arizona camp. Bartlett departed there at five o’clock on the afternoon of 9 September 1851. He traveled until evening before camping. The next day he traveled eighteen miles south before turning abruptly to the west and continuing five miles along the base of some hills before camping. (158) Lewis Spring on the Río San Pedro is twenty-two miles south of St. David. If Bartlett made four miles the afternoon of the 9th, then eighteen miles farther south would put him at Lewis Spring, where he turned and marched along the north end of the Huachuca Mountains. His map supports this interpretation. (159) Bartlett reported that his camp the night of September 10, 1851, was where he “afterwards learned that this was a place where Papagos Indians resorted annually to collect the Maguay.” (160) I interpret that Coronado traveled northward along the Río San Pedro as far as Lewis Spring, where he turned to the east to go through Government Draw and into the Sulphur Springs Valley. (161) If I am correct, then Coronado and Bartlett both visited Lewis Springs, and, moreover, both accounts of those visits have maguey in common. Juan Jaramillo wrote that Coronado had received gifts of the “pulpy leaves of roasted maguey” while he was along the arroyo Nexpa. (162)

As a consequence of the Bartlett survey, the Gadsden Treaty of 30 December 1853 was signed, and resulted in the United States gaining the land along the 32nd parallel. Immediately the United States made plans to survey a proposed railroad route through that region. Lt. John G. Parke initiated the survey in January 1854. According to Sulphur Springs Valley historian Vernon B. Schultz, the first survey by Parke “was through Apache Pass, but this route proved to be unfavorable because the grade was two hundred feet to the mile. Parke then made a reconnaissance around the northern end of the Dos Cabezas and south of Mt. Graham, where he discovered an easy and practicable route.” (163) This is where the tracks were laid.

The effect of trail blazing by the Fremont Association in 1849, the Bartlett survey in 1851, and the Parke reconnaissance in 1854 was the virtual abandonment of the Gila Trail through San Bernardino. The new road entered the eastern Sulphur Springs Valley from Apache Pass and continued to Sulphur Springs itself before reaching Dragoon Spring on the western side of the valley. This trace eventually became the Butterfield Trail, passing about fifteen miles north of Kuykendall Ruins. Thereby the situation with the ruins remained the same – they had been bypassed on the south by the Gila Trail, and were likewise missed on the north by the Butterfield Trail.

Spicer reported that by the late 1850s, the Chiricahua Apaches were “willing to allow [Anglo] settlement providing settlers paid them for the privilege of mining or ranching on their land. Some Anglo ranchers had begun to do this.” (164) There is no evidence that such activities occurred at Kuykendall Ruins. In 1861 the infamous event in which U. S. cavalry officer Lt. Bascom took Cochise hostage ended any peace with the Anglos. Construction of Fort Bowie began on 28 July 1862. This ensured the presence of United States soldiers in the region until after September 1886, when Naiche and Geronimo surrendered. There is evidence in the form of U. S. military ammunition, discovered during our metal detector searches, that cavalry soldiers of the Fort Bowie period were at Kuykendall Ruins.

The first settlers in the Kuykendall area arrived after 1878. According to Vernon Schultz, the family of Brannick Riggs “went to the San Simón Valley and camped at Nine Mile Water Hole, living in tents and a covered wagon.” When the water failed, “Riggs packed up and moved through Apache Pass with the intention of going on to California; however, Mrs. Riggs liked the place at which they camped on the western side of the Chiricahuas and refused to go any farther.” (165) The site of the original Riggs ranch house, today known as the Old Home Ranch, was on Pinery Creek within a half mile of the present intersections of Arizona State highways 186 and 181. Brannick Riggs patented this site on 23 May 1888. (166) It is nine miles east-northeast of Kuykendall Ruins. The oldest patent within seven miles of Kuykendall Ruins was that of James Lang in 1891. (167)

William R. Turvey patented the actual Kuykendall site on April 15, 1913. (168) As I previously reported, homesteader artifacts discovered at the site include buttons marked “Copper Queen Store,” a famous mercantile emporium that was built in Naco, Arizona in 1900 and that operated until the 1930s, and a silver garment clasp stamped 1896. (169) These objects were found on the Turvey homestead. Additional early settler period artifacts found at Kuykendall Ruins include an 1888 dime, found on the James Wadkins homestead patented on April 22, 1914, a Leader shotgun shell dated 1901 found on the homestead of Charlie Eastep patented on August 26, 1914, and a silver button stamped 1924 found on the homestead of Mary Christophel patented on June 3, 1914. (170) The surnames of these settlers indicate that they were Anglo-Americans, not Hispanics.