The Coronado Exploration Program

A Narrative of the Search for the Captain General

In September 2004, anthropologist Carroll L. Riley encouraged me to attend a presentation in Glenwood, New Mexico by historians and foremost Coronado scholars Richard and Shirley Cushing Flint, who were affiliates of the “roadshows” associated with the Coronado Project.1 Shortly after that presentation, I began continuous exploration for evidence of the Coronado Trail, an effort that resulted in the likely discovery of both Chichilticale and the 23 June 1540 camp of the Advance Party of the expedition. My findings have been published as reports in four issues of the New Mexico Historical Review. In addition, I have developed a permanent website where photographs of the artifacts our team discovered are displayed.2 Because of the availability of these previous publications and the permanent website, I will repeat here only a few points that have previously been publicized and, instead, devote the majority of this piece to material heretofore not reported. I shall also respectfully respond to the Flints' 2006 recommendation of what to include in a narrative. Readers should be aware that this report was current to October 2010. Subsequent to that date, however, my 2011 NMHR paper reported that we had discovered at the Slash SI Ranch on Big Dry Creek, New Mexico a ball of Spanish lead, an artifact composed of Spanish lead, and several metal artifacts consistent in form, function and craftsmanship with the sixteenth-century. We consider this a discovery of a third Coronado campsite. Details of this discovery will be presented in an article published in a future issue of the New Mexico Historical Review.

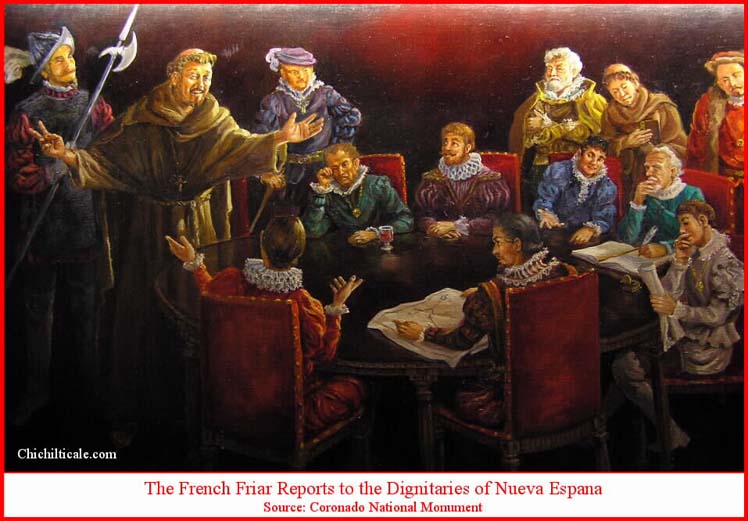

Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset stressed that the target of a hunt should be scarce and worthy.3 Accordingly, since I knew nothing of the Coronado Expedition, I first needed to be assured that Chichilticale was a deserving goal for an exploration program. The Flints persuaded me of such in September 2004 and I enthusiastically began my quest, knowing that a good hunt is hard to find. From the beginning I followed a carefully designed plan to explore for the Red House and other Coronado camps. Foremost, I was cautious and deliberate about the data to which I exposed myself – I wanted to avoid having to unlearn something. I asked the Flints to provide me the documents they considered to be written by people knowledgeable of the expedition and to have been written during or shortly after the time of the event. In the end, they furnished me fourteen such writings, which I refer to as the “original source documents.” Because Southern Methodist University Press had not yet published the Flints' masterpiece Documents of the Coronado Expedition, 1539 – 1542, Richard and Shirley sent me Microsoft Word files of the writings as they would appear in the pending tome. These files were not annotated and were written in Spanish because, although the Flint’s translations from the Spanish to the English are excellent, I wanted to read the original Spanish, and I insisted on avoiding annotations because I feared these as opinions. Per my request, the Flints kindly sorted the fourteen papers by date written, earliest to latest, and I studied the documents in that order.4

You have written extensively, in your journal, on formulation of a predicted route for the expedition through Sonora, southeastern Arizona, and southwestern New Mexico. As I see it, the argument for the route is at least as important in the case for consideration of Kuykendall Ruin as Chichilticale as is the subsequent discovery of a likely artifact from the expedition at that site. The artifact becomes much more meaningful in the context of a comprehensive route prediction, made prior to any knowledge of Kuykendall. Before launching into a description of fieldtrips and archaeological investigations, you need to spell out, in two or three paragraphs, the rationale for the route you formulated.

This is especially true since the route is different than the one proposed by the eminent historian Herbert E. Bolton, and held to doggedly by his many modern adherents.

It does, however, match in broad outline, the routing that we posited in our recent sourcebook Documents of the Coronado Expedition--see note 59 to Document 30. Further, it is consistent, in the large view, with Carroll Riley's recent statements in print about this portion of the route. These facts can be significantly employed in the article, since you reached your route hypothesis independently of our own and Riley's work. Indeed, although we had conversations with you during this process, you insisted that we not inform you of our own thinking on the subject of the expedition's route.5

This suggestion by the Flints resulted in three paragraphs contained in the first report devoted to a reasoned explanation of my interpretation.6 Here I offer a more thorough response to the Flint’s recommendation.

Unknown to me at the time of my 2004 – 2006 contemplation, my approach of insisting that I not be influenced by previous researchers had been advocated by at least two notable scholars. The 2006 writing of my initial report for the New Mexico Historical Review caused Richard Flint to provide me a National Park Service (NPS) booklet concerning a proposal to establish a Coronado National Trail. My perusal of the document caused me to seek and obtain the actual public comments made during the NPS hearings on the proposal.9

The comments included a statement by Madeleine T. Rodack, former ethnohistorian at the Arizona State Museum, offering her ideas on how to find the Coronado Trail:

When I mentioned the Rodack remark to Carroll Riley, he replied, “Madeleine was a great mind. She and her husband traveled with my wife Brent and me. She died a few years ago.” Riley recalled that another deceased scholar had also suggested such a method, and he pointed me to a statement by Charles W. Polzer, S. J., former curator of ethnohistory at the Arizona State Museum:

Reconnaissance, though, must be guided by 16th century documents. And I suggest that the only way we can interpret what is being said in these documents is to test it out on the ground. You will find out that a certain reconstruction doesn’t make sense when you are in a particular topographical region or sector. And so you have to go through a whole new rethink for the Coronado expedition.

I think it would be good for all of us to take everyone’s bibliography and burn them. Because if you follow all that stuff, you are bound to get confused. We don’t know who is right. The limitations of the documents are such that they leave so much open to interpretation that you and I are bound to become very confused when we try to put it all together. If we insist on our own work on the primacy of archaeological reconnaissance, we are going to do the best job we can with respect to the Coronado expedition problem.11

Unwittingly, I had followed the approach advocated by Rodack and Polzer. Mindful of our success in locating Chichilticale and the 23 June 1540 camp, the advice tendered by these two astute scholars, both deceased and perhaps unaware that their suggestions led to such rewarding results, prompts a respectful salute to both these sabios.

Juan de Jaramillo described the turn toward his right hand:

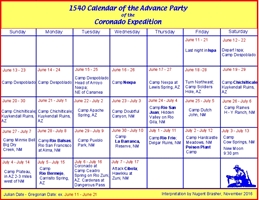

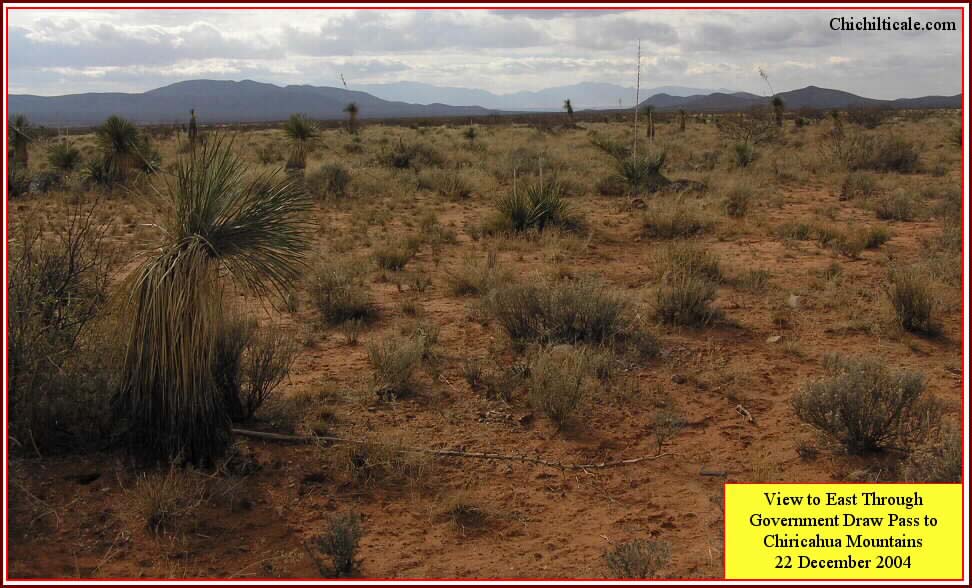

The right-hand turn occurred after traveling two days downstream along Arroyo Nexpa. I considered the Nexpa to be the modern Río San Pedro. The head of the Río San Pedro is at a drainage divide east of Cananea, Sonora. I counted the first day of travel downstream to be from the drainage divide to a point west of Sierra San José, about five miles south of the modern international border. The next day Vázquez de Coronado reached Lewis Spring, where he found Indians gifting maguey. The following morning he made the right-hand turn to the east and started up Government Draw. Had Vázquez de Coronado not turned east at Lewis Spring, the next opportunity lay two more days downstream at either Dragoon Wash or Tres Alamos Wash. Of these three options, Lewis Spring best fits the temporal aspect of the Jaramillo narrative.17

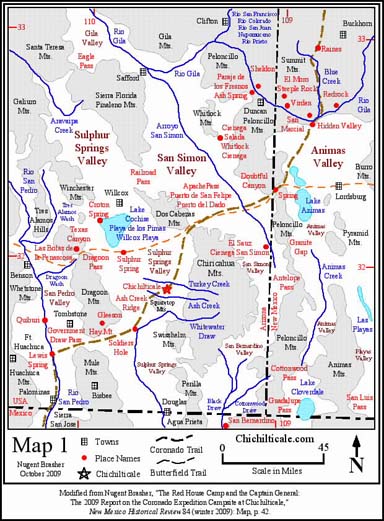

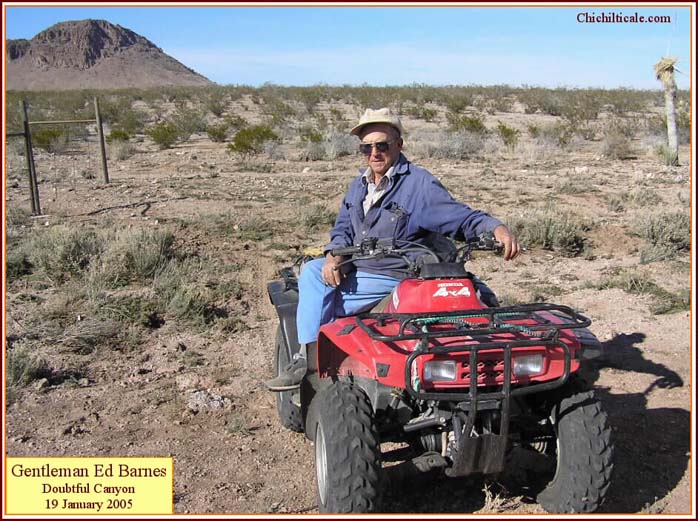

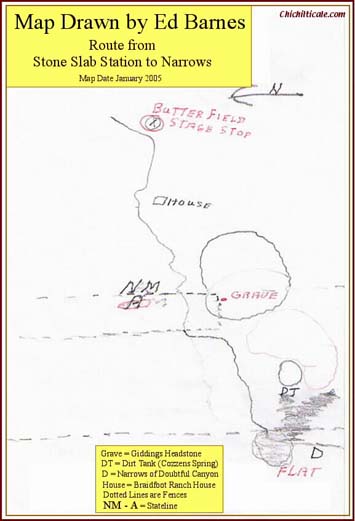

The unanimous conclusion of knowledgeable locals in Greenlee County, Arizona, and in Catron, Grant and Hidalgo counties, New Mexico was that following Blue Creek offered the only viable route. An elder member of the Kartchner family recounted memories about driving cattle “down the Blue [Creek]” because that route presented the only source of reliable water on a "tolerable" trail. These knowledge-based opinions voiced by local ranchers and hunters, coupled with my evolving exploration model disfavoring a Blue River route, swayed me to settle on the Blue Creek trail in New Mexico. This choice reduced the attraction of the Cienega Salada (Whitlock Cienega) and Paraje de los Fresnos (Ash Spring) prospects and increased my interest in the Doubtful Canyon and Hidden Valley prospects. (See Map 1)

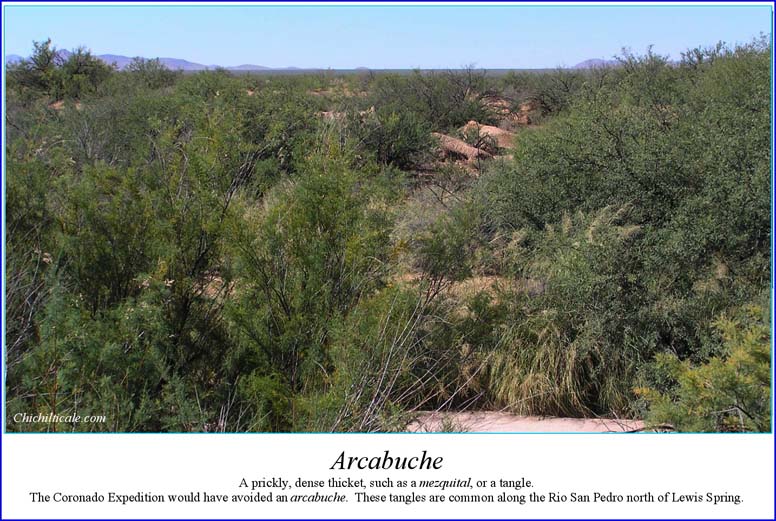

To field test my interpretation I drove to the Mexican border at Palominas, Arizona and began my way north, using a video camera to record the landscape along the trace. Accommodating ranchers provided me keys to their gates, and in some instances guided me to requested locations. Along the way I quizzed these ranchers about cattle drive trails, historical places, Indian camps, water and terrain conditions, and artifacts they had found or seen. I became convinced that the travel times and campsites I had predicted were feasible alternatives. Map 1 shows routes and campsites mentioned above.

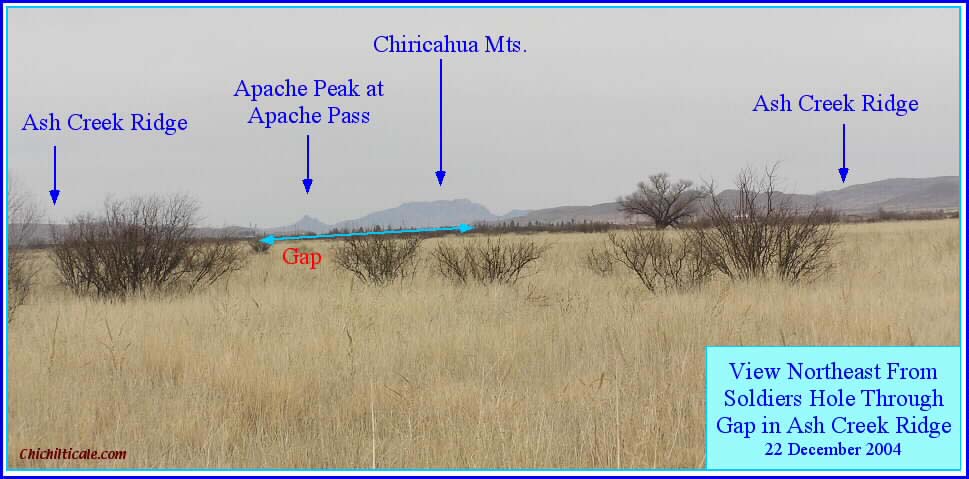

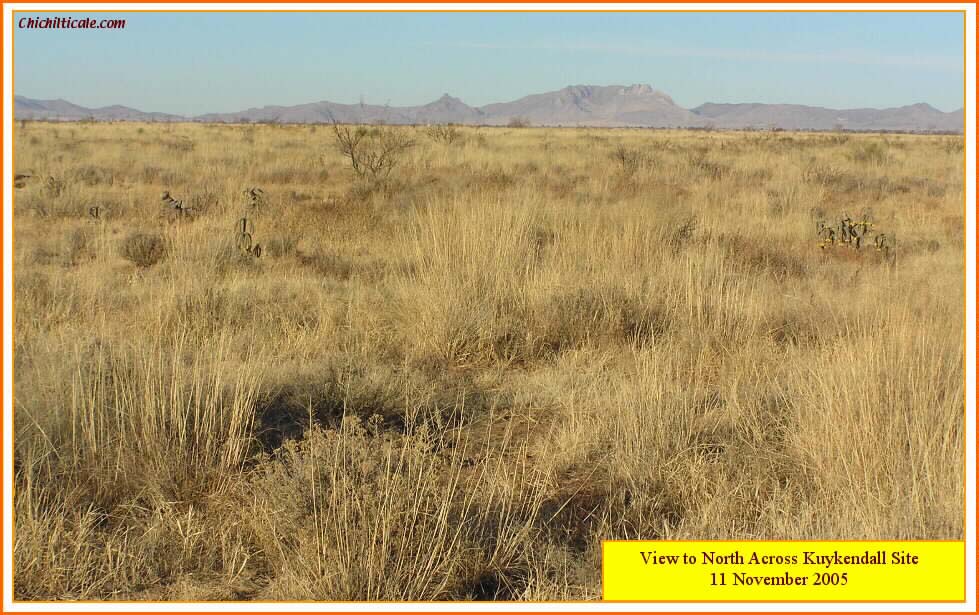

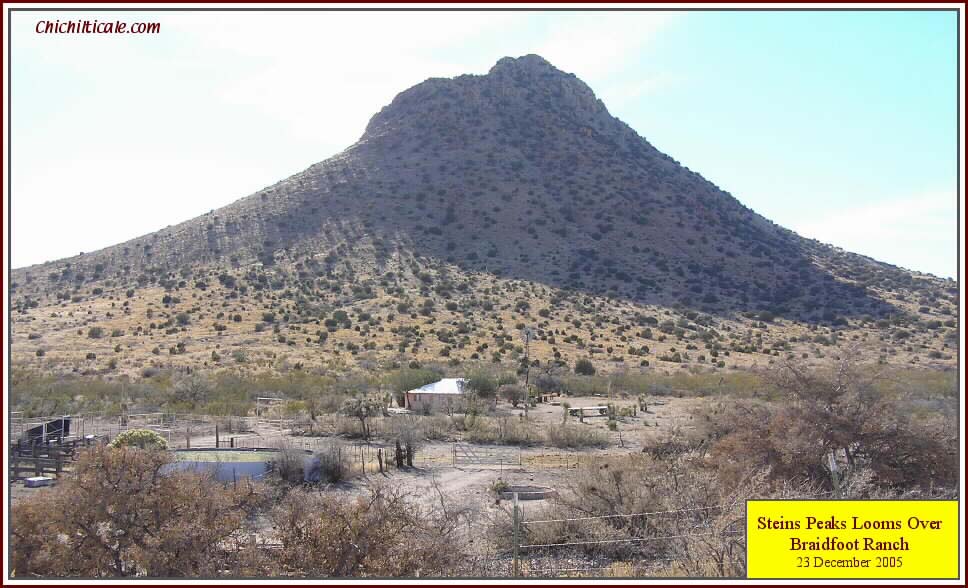

I carefully observed the topography upon entering the southwestern side of Sulphur Springs Valley after traveling upstream along Government Draw and rounding the southern end of Hay Mountain. Due east across the valley rise the north-south trending Chiricahua Mountains, creating the dominant range. However, the farther northeast one travels, the more obvious it becomes that the Chiricahuas appear to turn sharply to the west, creating an east-west trending mountain range that seems to block passage to the north out of the valley. These apparent blocking mountains are not the Chiricahuas however – they are the Dos Cabezas and the Pinaleños, all actually trending northwest, but producing the illusion of a single east-west range. After passing through Ash Creek Ridge Gap just a few miles southwest of Kuykendall Ruins, the illusion becomes even more noticeable – with the Winchester and Galiuro mountains adding to the apparent east-west range. In the distance to the northeast, at the place where the sharp turn begins, is a prominent break in the mountain range. This is Apache Pass, where the Chiricahua and Dos Cabezas mountains join at an angle at a topographical low point. The vista clearly shows Kuykendall Ruins located where the mountain chain turns west toward the Sea of Cortes, and where the mountain is broken so as to allow passage through the range. Identification of this major landmark within the predicted travel corridor elevated my confidence.

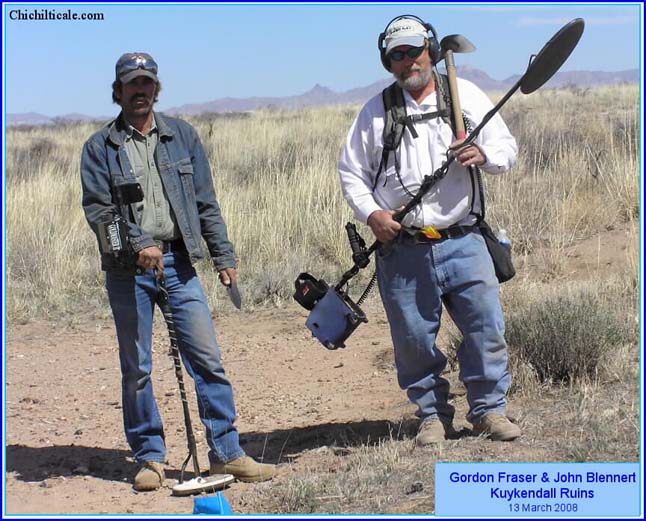

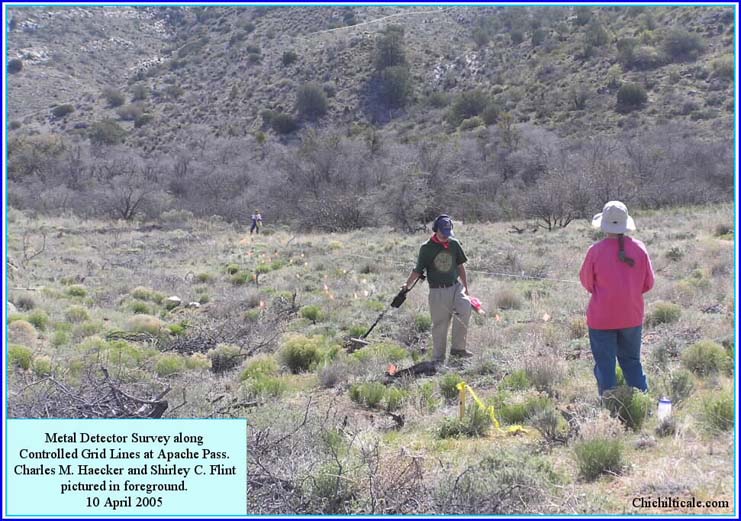

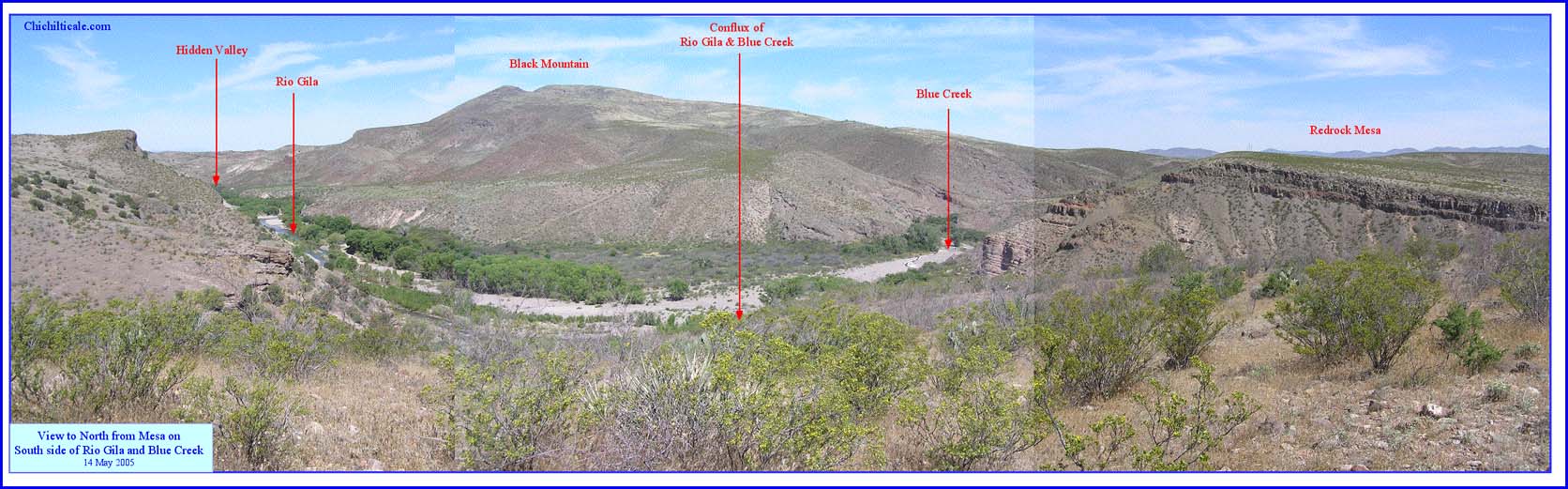

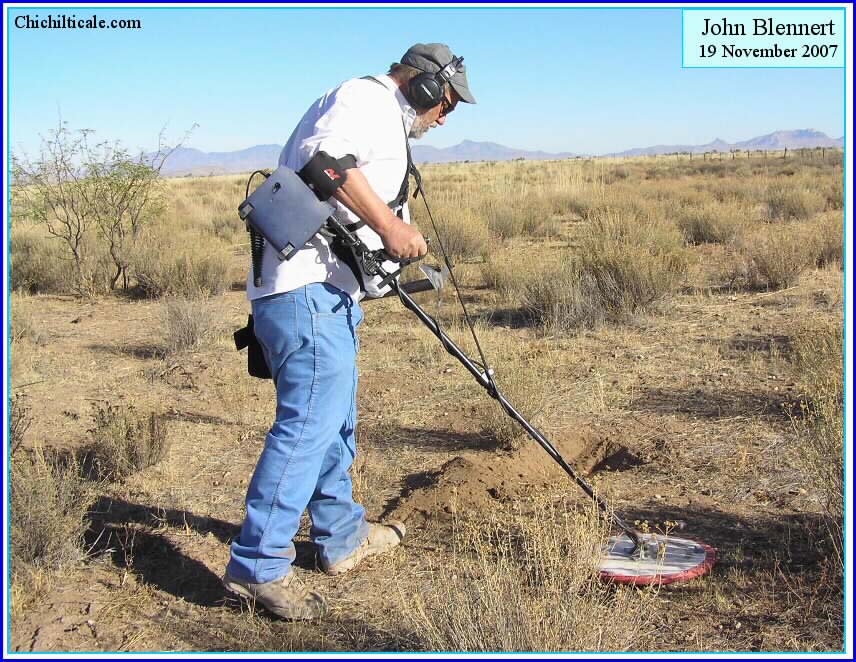

In December 2005 I formed an exploration team. We cleared the vegetation from about forty acres of the site, and in January 2006 we embarked upon our first field season. During that initial season we discovered an iron crossbow bolthead while exploring with hand-held metal detectors along one-meter spaced grid lines. This created great enthusiasm, and two subsequent field seasons exploring with technologically advanced Blennert sleds produced a significant number of iron artifacts consistent in form, function and craftsmanship with sixteenth century pieces, as well as two lead shot composed of Spanish lead.21 We have concluded that Kuykendall Ruins more likely than not represent the fabled Red House called Chichilticale.

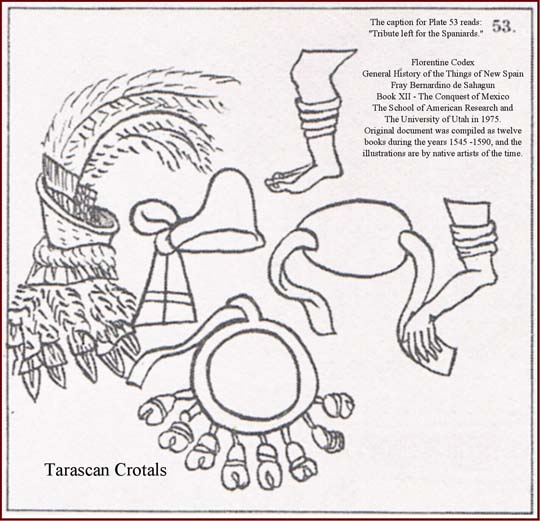

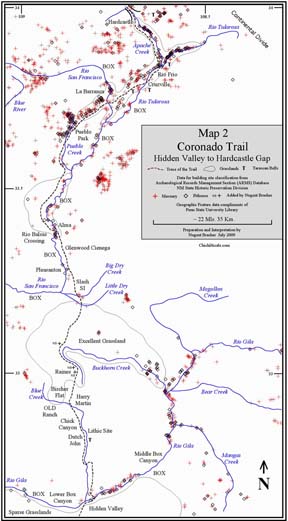

Although I primarily relied on the fourteen original source documents of the Coronado Expedition to establish my predicted travel corridor, I also considered that the Captain General was guided by Indians, and I suspected that the trail followed by the expedition was old, well established, and used for trade, long-distance travel and for connecting settlements. We discovered Tarascan copper crotals at Kuykendall Ruins, suggesting evidence of a prehistoric trade trail. Other Tarascan bells have been reported along our predicted travel corridor. (See Route Map and Map 2) I have previously written about the significance of the Tarascan copper bells and of other archaeological evidence supportive of my proposed route being an old trade trail.23

Concurrent with determining the travel corridor, I was concerned with the requirements for a Coronado campsite. I reasoned that expedition campsites required water, shade, fuel wood, fire rocks, and accommodating space – enough space for grazing and camping for some two thousand people or more and as many as seven thousand livestock.24 The Jaramillo narrative strongly influenced my campsite prediction for the Advance Party because it controlled my daily distance estimates for that specific group, thereby controlling the spacing between Advance Party campsites.

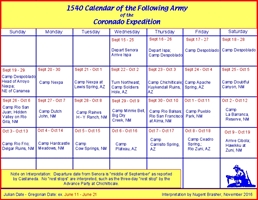

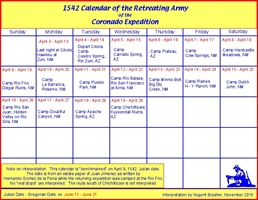

To prospect for specific campsites within the travel corridor, I addressed the pace of travel for three groups of the Expedition – the Advance Party, the Following Army, and the Retreating Army. At Culiacán Vázquez de Coronado selected a group of horsemen and indios amigos [Indian allies] to proceed ahead of the army because of his concern about availability of food and his judgment that the entire group could not make the trip together without "a huge loss of people." Castañeda implied that the Captain General traveled light so that he could proceed rapidly.25 I constructed travel calendars for the three parties of the expedition. I used the measurements from the Advance Party pace of travel to predict their campsites, and I assumed the same pace of travel for all three calendars. This, of course, is unrealistic for the slower traveling Following and Retreating armies, so those calendars are employed solely as a model to determine general time of month – the calendar for the Advance Party serves for the fleet of foot, but not for the bulky Following and Retreating armies. These last two armies traveled slower, necessitating more campsites than those of the Advance Party. This means that the Following and Retreating armies might have used additional, less suitable campsites along the trail.

Using these criteria I predicted specific campsites within my proposed corridor of travel. At the same time, however, I recognized that while the search must be for all fitting campsites along the corridor of travel, this is not the principal consideration for exploration. Because the metal detector is currently the preferred and proven technology for finding expedition artifacts, it is foremost that prospective campsites have a sixteenth-century surface that can be explored with such a device.

The initial exploration model yielded "a total of eighteen primary exploration prospects in the United States, each being a campsite of the expedition as it traveled from Ispa to Cíbola. I identified many secondary exploration prospects – specific locations where terrain forced the expedition to pass through.”26 My exploration program called for evaluating the feasibility of conducting surface reconnaissance and metal detecting at these primary and secondary prospects. Field reconnaissance observations, land ownership, and ease of access influenced my selection of prospects to explore with a metal detector.

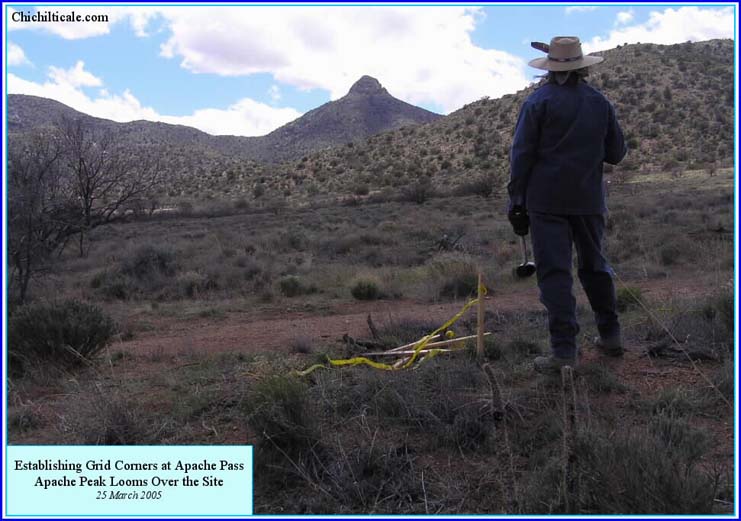

The exploration model pointed at Apache Pass as a campsite prospect. The location was spacious enough for the expedition, provided sufficient grazing for one night, contained shade, fuel wood and fire rocks, and supported a spring-fed, elongated watercourse. We conducted a very limited hand-held metal detector survey there in April 2005. The survey area was selected on the basis of ease of metal detecting a one-meter grid spacing. Nothing of consequence to the Coronado Expedition was discovered.27 Field reconnaissance of Hidden Valley, another primary prospect, demoted that location to the lowest potential for finding artifacts because repeated flooding had destroyed the likely campsite. Federal and State land ownership further demoted Hidden Valley as a practical prospect.28

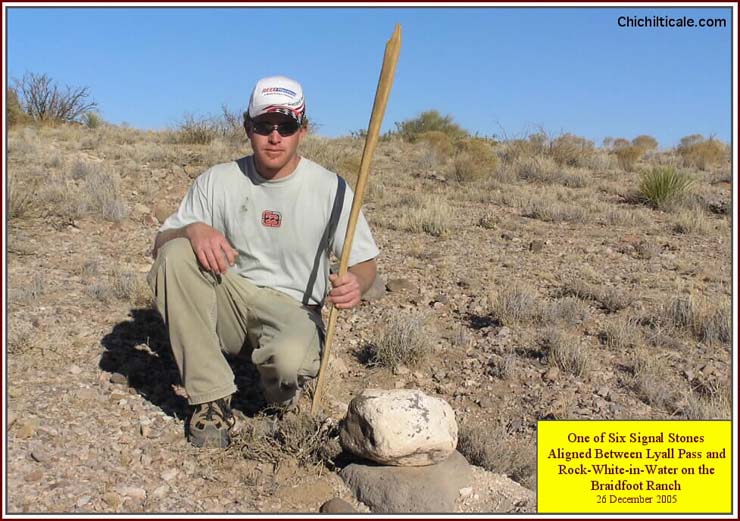

In February 2009 we determined by lead isotope analysis that the ball found in March 2005 in Doubtful Canyon was composed of lead from Spain. This motivated us to measure the isotopes of twelve lead shot we found at Rock-white-in-water in January 2009. By this method, we determined that the lead in four of these shot was from a Spanish source location. Our success prompted us to return to Doubtful Canyon in September 2009, and we found three wide, round-headed, short-shanked tacks identified by historian and nail expert Eugene Lyon as estoperoles consistent in form, function and craftsmanship with those found at Santa Elena. The distribution of the whole assemblage of artifacts extended over 1.87 miles along Doubtful Arroyo, creating a spread of a magnitude expected for encampment of a group the size of the Coronado expedition. The totality of the spatial distribution and the diversity and number of pieces included in the artifact collection compels us to believe that Doubtful Canyon served as a campsite for the Coronado expedition. The report of our Doubtful Canyon finds and lead analysis is in the Summer 2011 issue of the New Mexico Historical Review.31

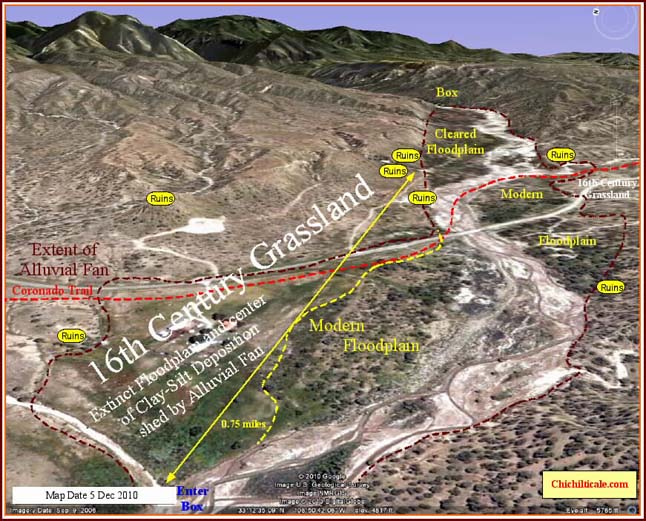

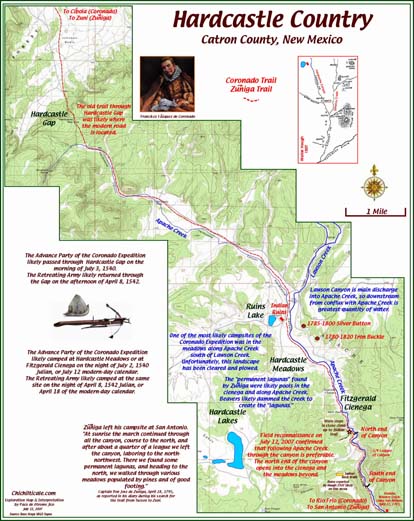

My exploration model included the trace of the Coronado Trail and specific campsites of the Advance Party. The model included a trade and settlement trail model. The Route Map and Map 2 display my predicted trail from Hidden Valley on the Río Gila (Río San Juan) northward to Hardcastle Gap as passing through archaeological pithouse and masonry building sites. The distribution of these prehistoric settlements traces a trail. I settled on the trace of my predicted trail in January 2005. Although I was aware of the most well-known archaeological sites along my proposed route, my first look at a detailed posting of the majority of the sites was in July 2009, when I created Map 2. The dominant number of prehistoric settlements along my proposed trail was reassuring.33

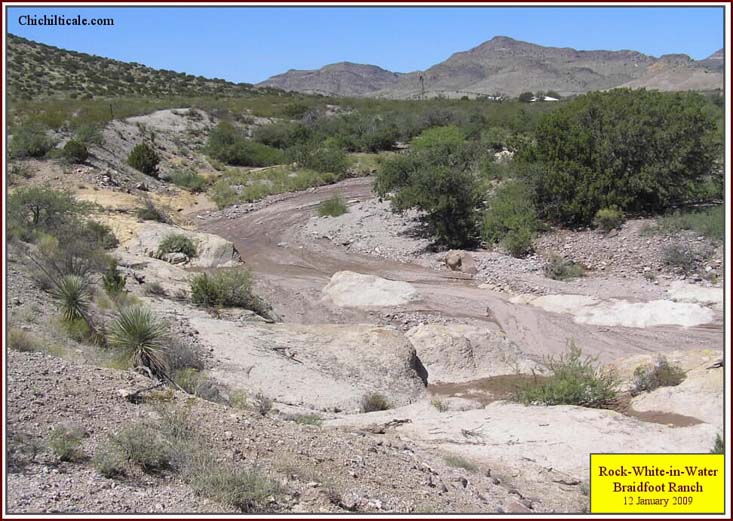

The Route Map and Map 2 illustrate that Hidden Valley sits between two major box canyons along the Río Gila. Hidden Valley is an "only" spot – the only place travelers can reach or depart the river on both sides. This forces the trail to be there. Hidden Valley was in the Despoblado, the Unsettled Land. In the sixteenth-century the settlements shown on the Route Map and Map 2 were already abandoned. Nevertheless they marked a long-used trade trail connecting deserted villages. Hidden Valley offered a campsite extending upstream to where Blue Creek enters the Río Gila from the north.

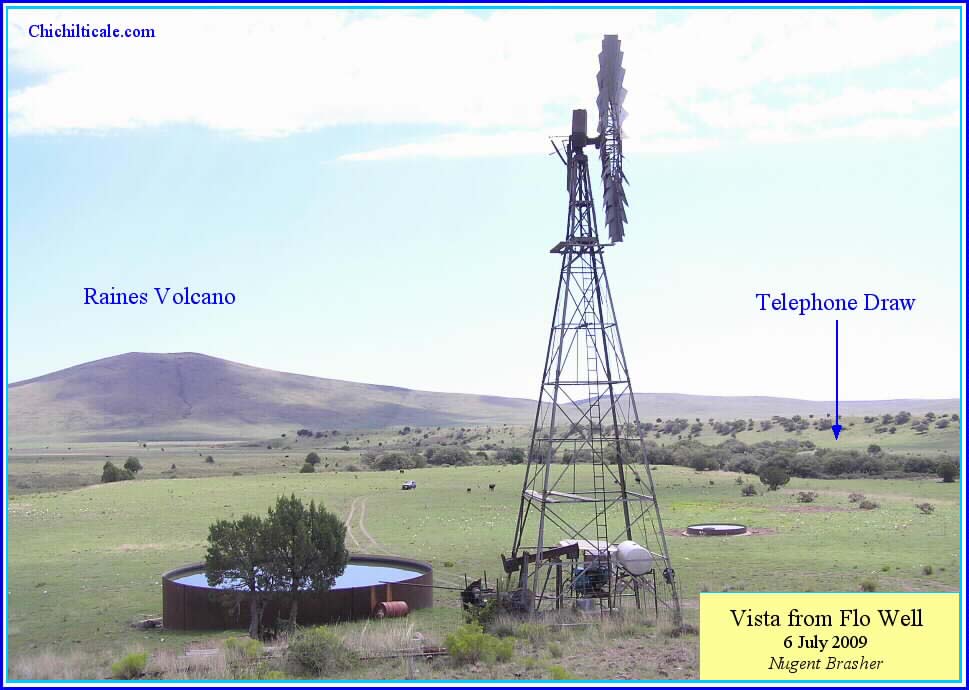

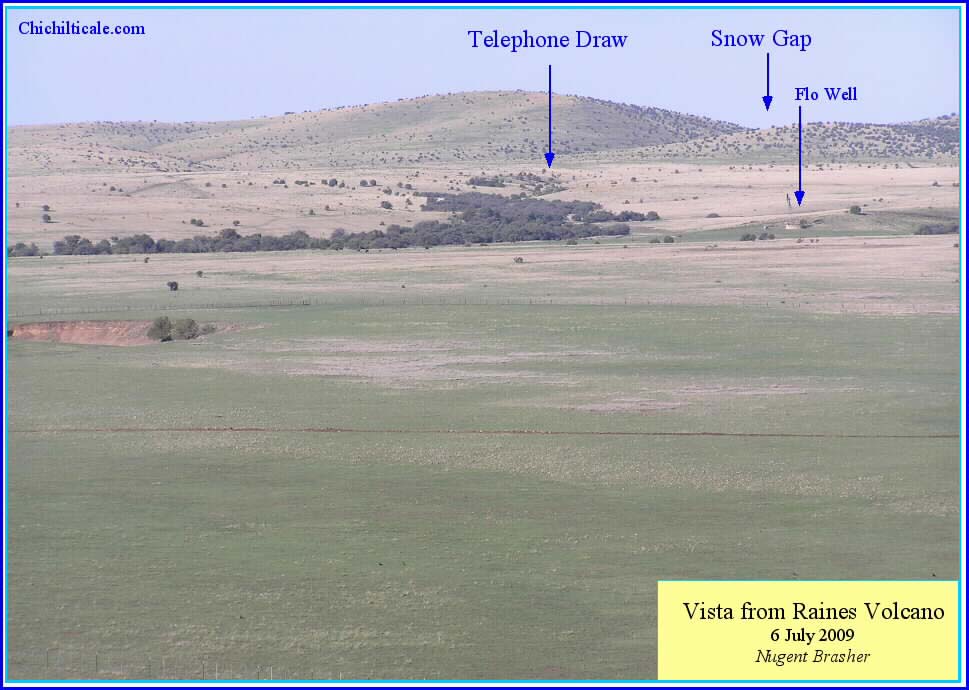

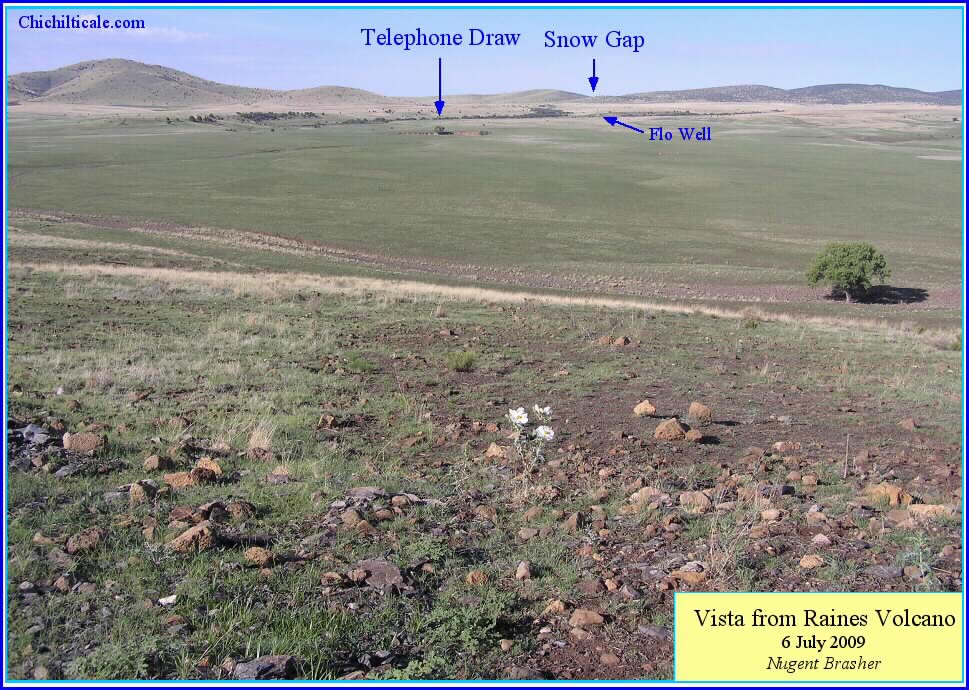

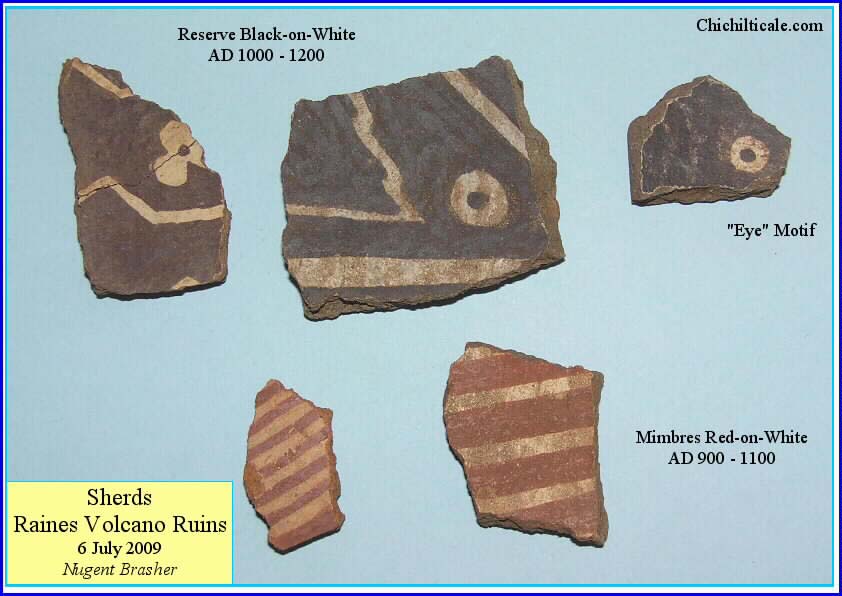

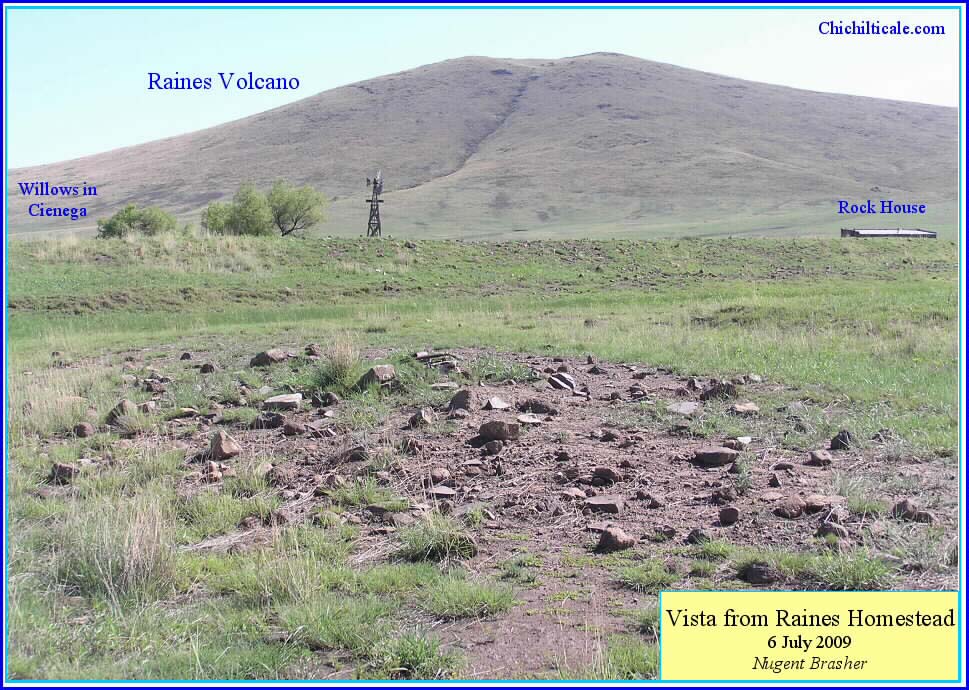

From where the northbound trail left Blue Creek, it headed toward the Raines Place, a level, expansive grassland containing a cienega, some wooded, elongated streams, and prehistoric masonry buildings, all lying on the western side of Raines Volcano with its distinct crater. My exploration model portrays the Raines Place as an almost certain campsite because of these characteristics. About eight miles separate Harry Martin, Bircher Flats or OLD Ranch from Raines. Unless the expedition camped at Bircher or OLD, the Raines camp would represent the best grassland for northbound armies since leaving Doubtful Canyon.

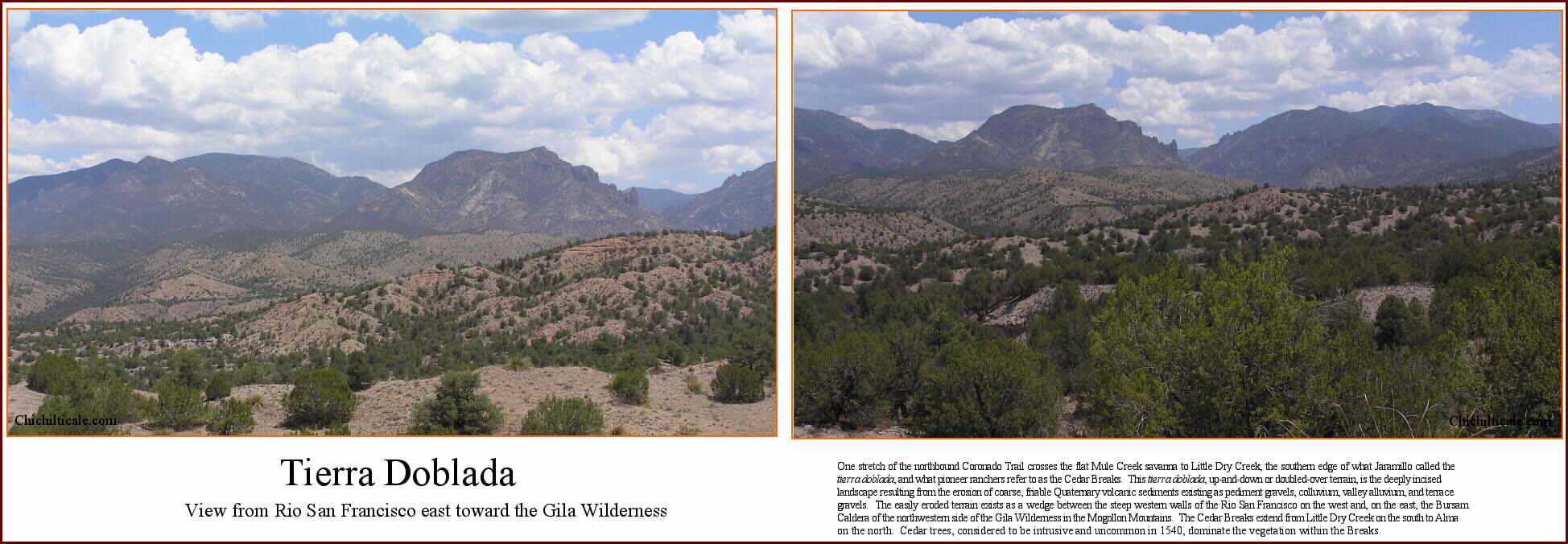

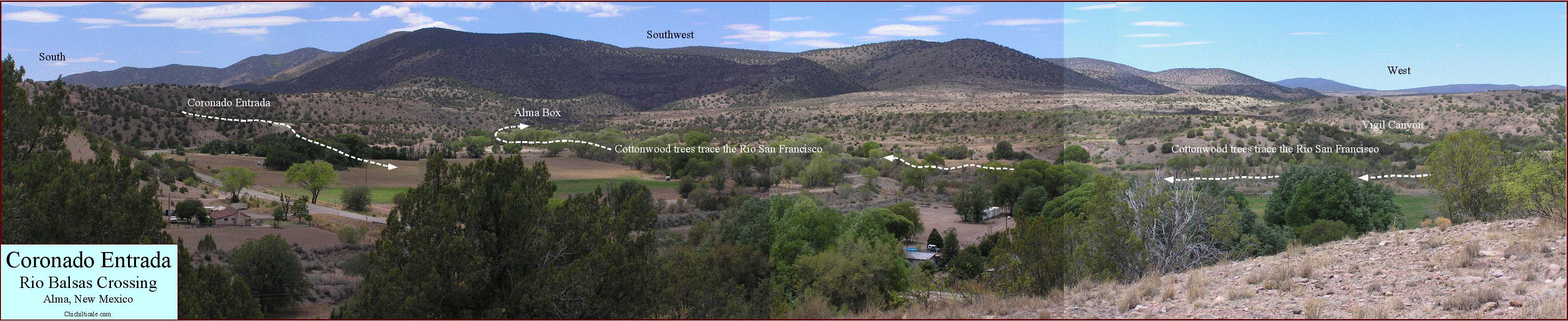

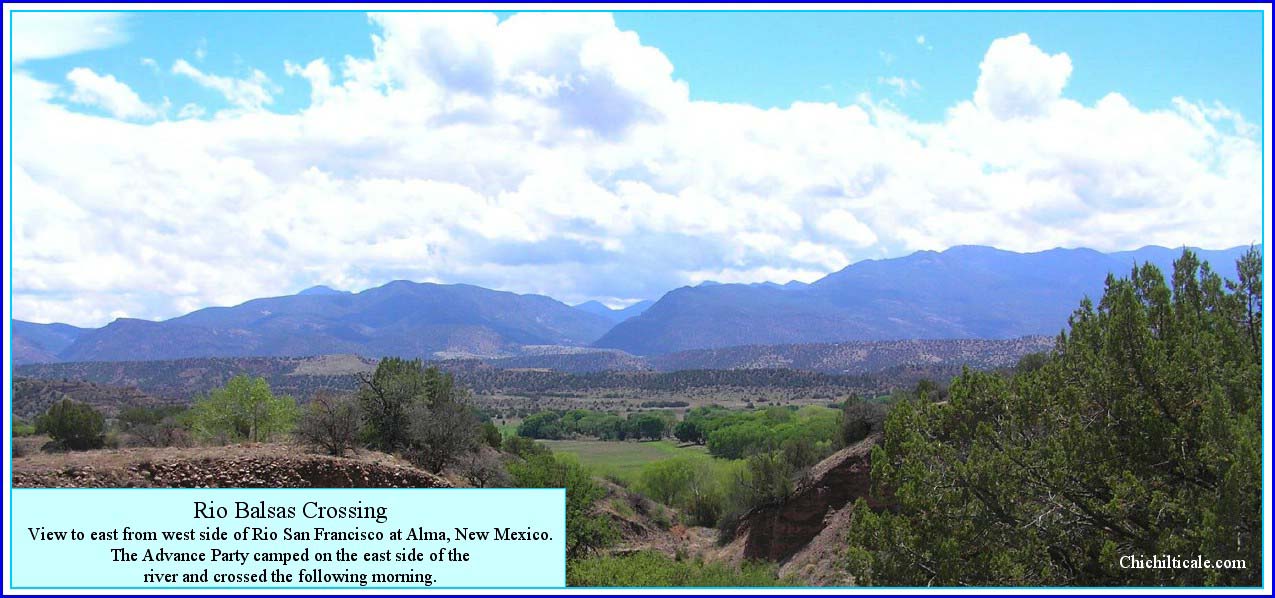

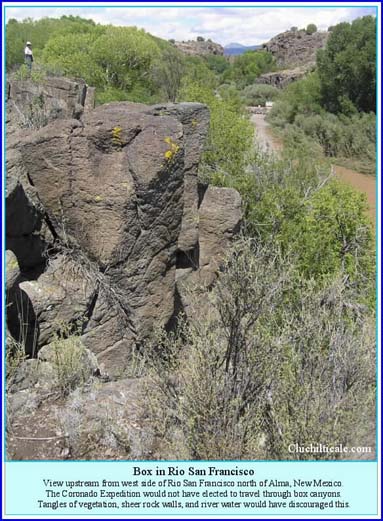

When the Advance Party reached Alma, its members found a small valley with grazing for animals and enough space for any of Coronado's parties. They also found a swollen (crecido) Río San Francisco.36 Vázquez de Coronado suffered a forced crossing of the swollen waterway because he was following the de facto Indian trail, and Alma was where the trail crossed the river. Alma is located at a small opening between lengthy box canyons. The southern box extends upstream from where the Río San Francisco joins the Río Gila in Arizona to Alma, site of the Río Balsas crossing. Upstream from Alma is the northern box, extending from Pueblo Creek to the Río Tularosa. The Route Map and Map 2 show few prehistoric residences in the Río San Francisco, and I suggest that this is because it is a box. There are prehistoric settlements at Alma. This is because of the generally flat terrain and wider flood plain of the Río San Francisco at that spot. This is also where the first Anglo settlement was placed. The Route Map and Map 2 illustrate that prehistoric residences and the main trail tend to avoid boxes.

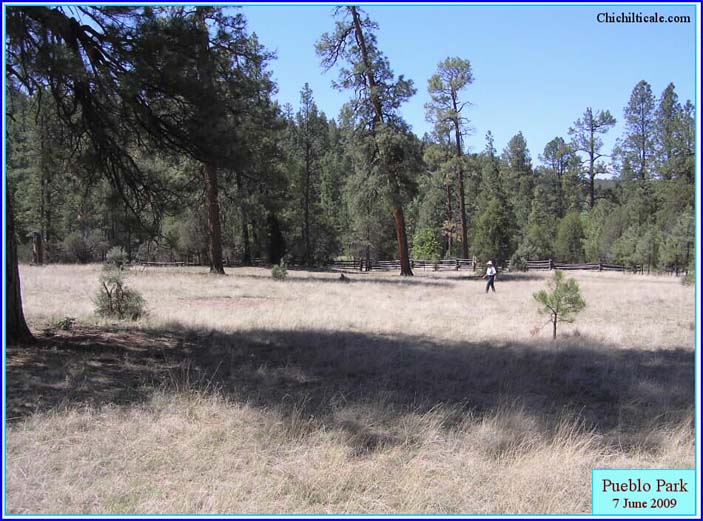

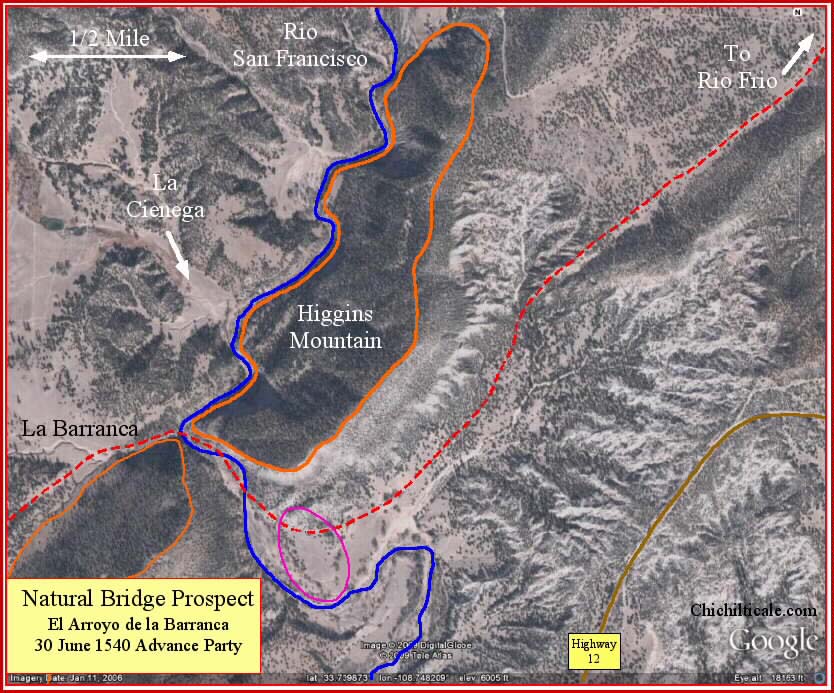

Map 2 clearly illustrates the dense settlement pattern connecting Pueblo Park, La Barranca, Río Frío and Hardcastle. This pattern marks the oldest trail, the one before the abandonment of the region by sedentary Indians after AD 1400, but still used by long distance travelers after that exodus. Trails like this seldom die. The settlement pattern of the late nineteenth century Anglos offers proof of this.

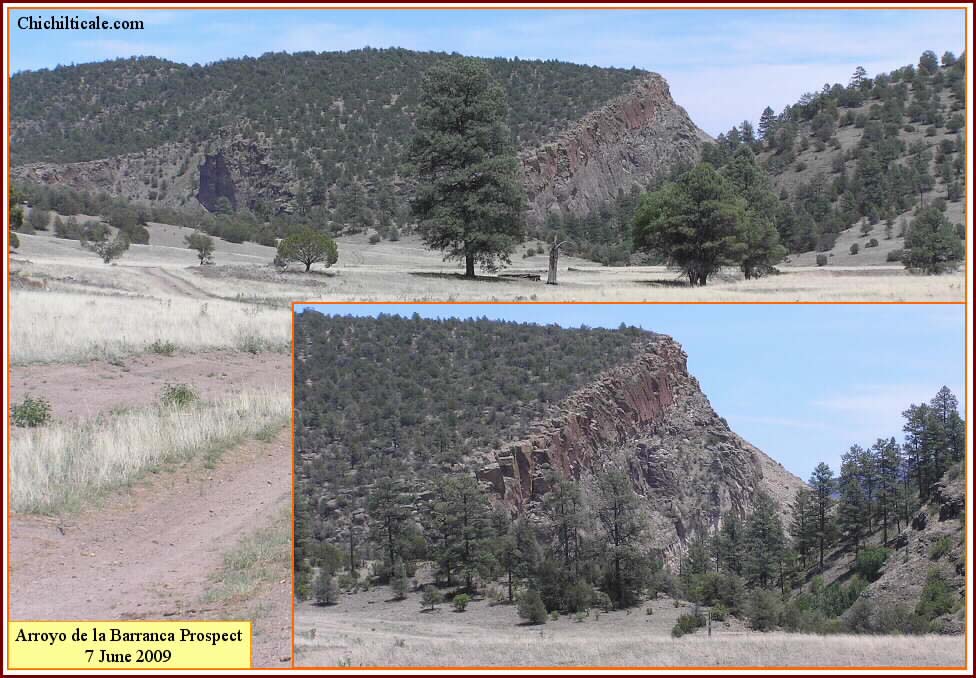

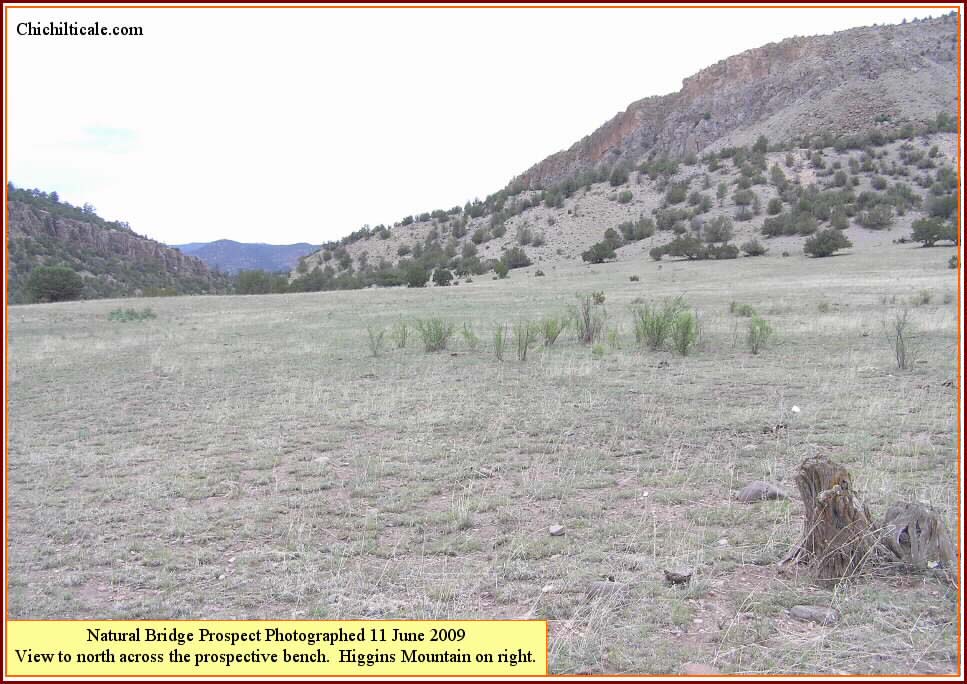

About six miles northeast from Pueblo Park the trail comes into grassland meadows extending essentially continuously to Hardcastle. The meadows offer easy walking and no shortage of water. There are three one-day-apart locations in these meadows where Coronado's multitudes could have camped. Juan Jaramillo described one of these as El Arroyo de la Barranca (Arroyo of the Canyon).39 I interpret that spot to be on the Río San Francisco about 16 miles from Pueblo Park where the south flowing river cuts through Higgins Mountain to form a spectacular canyon. Pithouses, masonry buildings, lithic and ceramic artifacts, and pictographs offer evidence of prehistoric occupation. Grassy meadows, fuel wood, water and shade provide good camping.

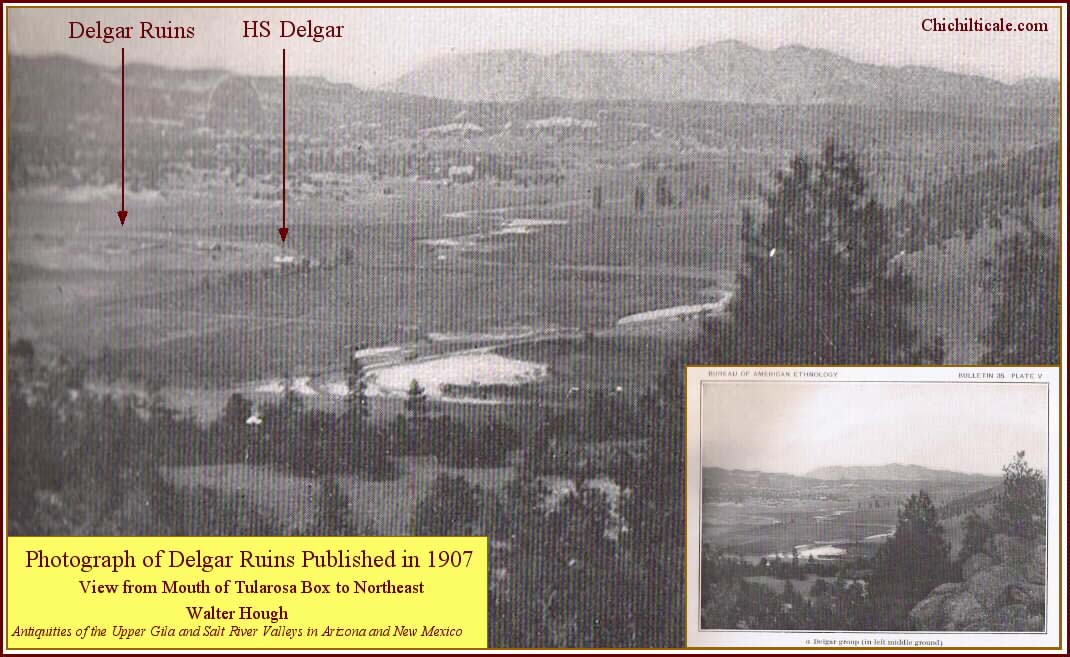

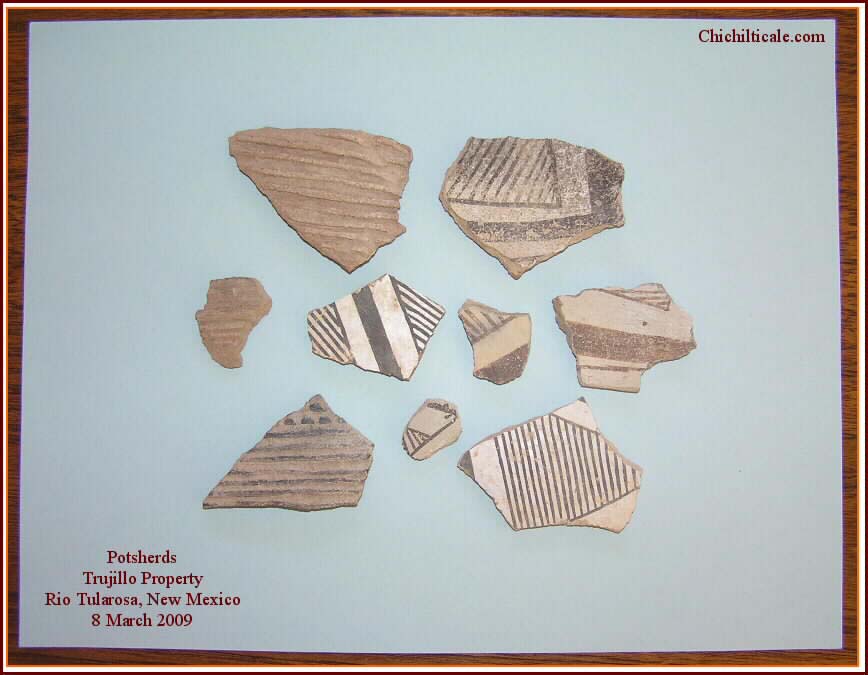

About eight miles northeast of La Barranca along my proposed route are Delgar Ruins at Cruzville, New Mexico. Here the Río Tularosa eases through a wooded, grassland valley some three to four miles long to the junction with Apache Creek. I interpret the Río Tularosa to be the Río Frío of the Coronado expedition. The stretch between Delgar Ruins and Apache Creek is a choice campsite, equal to the Raines Place or Chichilticale, and I suspect that the Following and Retreating armies lingered there for refreshment. At this camp there was sufficient time for a scribe and witnesses in the Retreating Army to prepare documents. In 1907 archaeologist Walter Hough described the setting as "one of the most beautiful valleys in the Southwest… In ancient times there was a large population who built numerous pueblos on the terraces overlooking the fields… The Tularosa valley is an important center of archaeological interest. The principal pueblo [Delgar Ruins] covers more than six acres… Metal working was not practiced, but trade bells of copper were brought from Mexico. One of these, a remarkable pyriform specimen three inches long, was taken from [Delgar Ruins]." Archaeologist Victoria Vargas reported Tarascan bells at Apache Creek, Delgar Ruins and the Upper Río San Francisco.40 Locals tell of finding scores of Tarascan copper bells in this area. The prevalence of these copper crotals offers evidence of a trade route with western Mexico, a connection that likely was followed by the Indian guides of the Captain General.

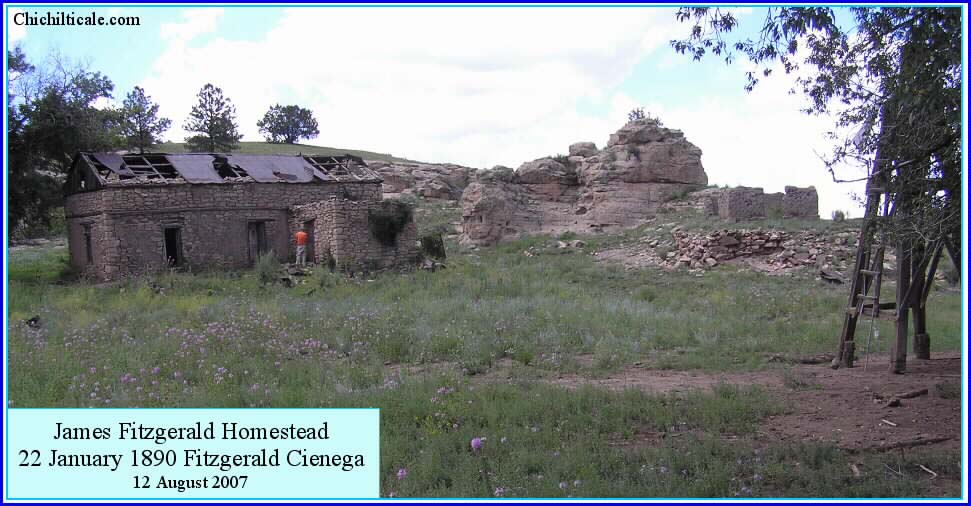

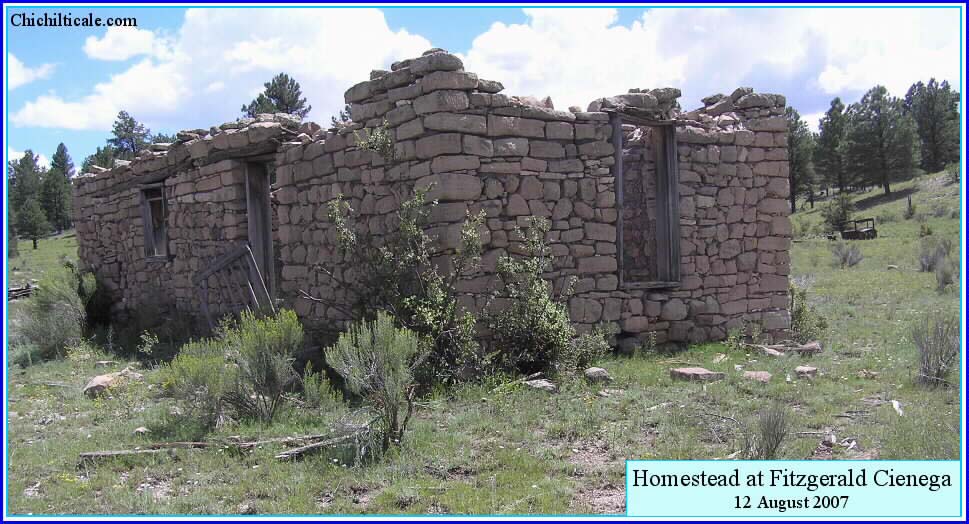

During the summers of 2007 and 2009 our team conducted metal detector surveys on a private ranch that included the cienega. We found no definitive sixteenth-century pieces, but we discovered two artifacts that likely belonged to the José de Zúñiga Expedition of 1795 from Tucson to Zuni. I previously wrote, "Zúñiga, hoping to find the Camino del Nuevo Mexico, may well have located the very trail that Vázquez de Coronado followed to Zuni. The later Spaniard's exploration indicates that the trail was old and well traveled."42 At Hardcastle we found prehistoric masonry buildings and stone stair steps worn smooth, which suggest a major trail crossing the valley. Photographs of this region are in the section titled "Post-Coronado Presence in Chichilticale Region." From Fitzgerald Cienega the trail passes through Hardcastle Gap, located about two miles north of the favored camping area.

I have proposed here a trail of some one hundred eleven miles from Hidden Valley to the Fitzgerald Cienega camp at Hardcastle. The Advance Party required eight travel days over this stretch, about fourteen miles a day, and it occupied nine camps along the way, including the Río San Juan camp at Hidden Valley and the Hardcastle camp at Fitzgerald Cienega. The Following and Retreating armies required more camps because of their slower pace.

Our team's success at Kuykendall Ruins and Doubtful Canyon lends credibility to the exploration model. The Doubtful Canyon discovery serves to exclude the likelihood of Vázquez de Coronado heading from the canyon toward the Sheldon, Arizona, area. Had he wished to go there, Vázquez de Coronado would have traveled through Whitlock Cienega and not Doubtful Canyon. Moreover, as I have discussed here, the difficult climb onto the Mogollon Rim from Sheldon would have discouraged the expedition from that route. From Doubtful Canyon the Captain General most likely crossed the northern end of Animas Valley and reached Hidden Valley on the afternoon of 24 June 1540, this being St. John's Day of the Julian calendar. This conclusion carries the question of where and how to search for the campsites along the trail described in the previous section.

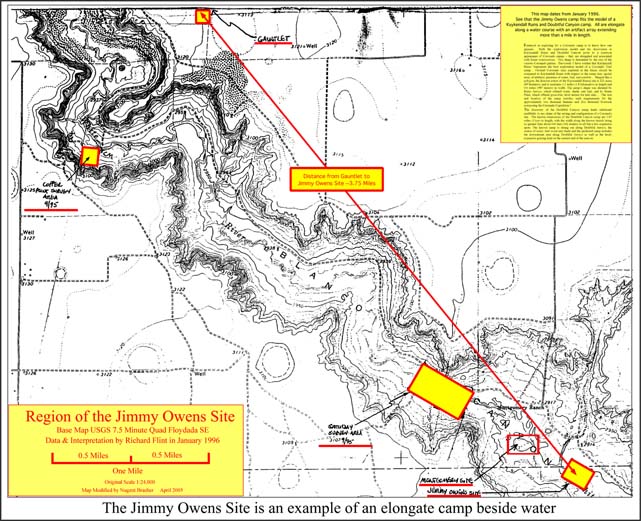

Foremost in exploration for a Coronado camp is to know how one appears. Both the exploration model and the discoveries at Kuykendall Ruins and Doubtful Canyon point to a common appearance of Coronado camps – they are elongated and associated with linear watercourses. This shape is demanded by the size of the various Coronado parties. Previously I have written that Kuykendall Ruins "represents the best exploration model of a Coronado Trail camp… On-trail Coronado sites explored in the future should be compared to Kuykendall Ruins with respect to the camp size; spatial array of artifacts; presence of water, fuel, and comfort… Shaped like a polygon, the [known extent of the Kuykendall Ruins] site is 221 acres (89 hectares), and it measures 1.1 miles (1.8 kilometers) in length and 0.6 miles (987 meters) in width. The camp’s shape was dictated by Ruins Arroyo, which offered water, shade, and fuel, and by Ruins Plain, which offered grass-free, level terrain for tent sites…. The size and location of the camp satisfies such requirements for the approximately two thousand humans and five thousand livestock composing the Coronado Expedition."44

The discovery of the Doubtful Canyon camp lends additional credibility to my claim of the setting and configuration of a Coronado site. The known dimensions of the Doubtful Canyon camp are 1.87 miles (3 km) in length, with the width along the known stretch being no greater than about 600 feet (182 meters) in all but a few expansive spots. The known camp is strung out along Doubtful Arroyo, the source of water, fuel wood and shade and the predicted camp includes the downstream area along Doubtful Arroyo as well as the level, expansive grazing land on the eastern end of the canyon.

From Bircher Flat on Blue Creek to near the Slash SI Ranch are expansive, excellent grasslands, but there are none specifically at the Slash SI camp on Big Dry. Along the proposed route there are no expansive grasslands from Little Dry Creek to the west side of the Río San Francisco at Alma. The first good grasslands north of Alma begin in meadows at a point about six miles northeast of Pueblo Park. From there grasslands in meadows extend to Hardcastle Gap.

Locations with grazing and abundant water and fuel wood offered the most desirable campsites. Spots such as these, when isolated by more than one travel day with less desirable locations between, are preferred places where the expeditionaires might have lingered. In the corridor between Doubtful Canyon and Hardcastle, the most preferred camps are at the Raines Place, the west side of the Río San Francisco at Alma, and the stretch north of Pueblo Park to Hardcastle Gap, especially at Delgar Ruins and Fitzgerald Cienega.

The grasslands on the western side of Raines Volcano offered an excellent Coronado camp. The Following and Retreating expeditions would have arrived there after several less desirable camps, suggesting that they would have spent time at the Raines Place refreshing the animals and thereby increasing the chances that those lingering groups left evidence of their presence. The Retreating expedition had as many as 6,220 animals and 1,550-2,350 people.46 I have seen several hundred head of black cattle scattered over the Raines Place, and the presence of some six thousand more animals would put livestock everywhere. There would be tents, fires, activity, grazing and watering. The occupied space would have been vast. The most prospective site at the Raines Place is along tree-lined Telephone Draw, which offered shade, fuel wood and water surrounded by rich grass. Evidence of Coronado's presence should be there. Fortunately for exploration purposes, the site has been only sparsely occupied, meaning that modern metal litter is rare and not intrusive to goal-driven metal detecting.

Fitzgerald Cienega offered all the comforts of a good Coronado camp. Unfortunately, the most prospective sites have been covered by sediment eroding from the mountainsides, which has buried metal to a depth beyond which a metal detector can sense. The rancher told me that he "gets fences buried," and I have seen tops of fence posts just above the surface. Topographic noses protruding into the valley offer a sixteenth-century century surface, and we have searched most of these, finding two artifacts identified as from the Zúñiga period. North of the private land is an area prospective for Coronado artifacts, but it is unavailable to me because it is U. S. Forest Service property.

Although the Dutch John camp may not have been one of the most preferred by Vázquez de Coronado, it nevertheless has exploration appeal. The Dutch John prospect is similar to the Doubtful Canyon camp. At Dutch John the Coronado expeditionaries would have spread out along Blue Creek because of the terrain. This would have scattered the residuals of the expedition and thereby create a risky exploration venture. The same circumstance exists at Doubtful Canyon, where the troop of campers extended for at least two miles along temporarily pooled water in Doubtful Arroyo. Despite this scattering that hinders exploration, both Dutch John and the Doubtful Canyon camp have locations that center the prospect. The permanent spring at Rock-white-in-water offered a focal point in Doubtful Canyon. The lithic site at Dutch John offers a similar attraction – prehistoric presence beside permanent water.

Good prospecting practice recognizes that the correct search for the Captain General is not simply for a potential Coronado camp, rather it is a search within the exploration model corridor for a sixteenth-century surface that can be metal detected, and that the best of these surfaces are where there also exists a desirable campsite. The resolution of the measuring device – interpretation of the historical record is the measuring device – is, unfortunately, not precise enough to pinpoint each exact campsite between Hidden Valley and Cíbola. Campsite prediction should be based on knowledge of the terrain and on history, and good prospectors will naturally employ geology to determine the feasibility of finding artifacts at any given prospect.

The Flints cautioned me that acceptance of my discoveries would be resisted because my proposed trail was "different than the one proposed by the eminent historian Herbert E. Bolton, and held to doggedly by his many modern adherents."48 The force of this belief was displayed during public hearings in 1991 when pressure to proclaim the Bolton route as the National Trail was exerted by Jerome J. Pratt, a retired National Park Service employee who brought with him six political representatives of Cochise County:

Feelings such as those expressed by Pratt were anticipated not only by the Flints, but also by the sixteenth-century Italian observer Nicoló Machiavelli:

Following the publication of my first narrative report of my explorations, several people familiar with the literature concerning the Coronado Trail asked me, “Why did you decide to explore at Kuykendall Ruins in light of the dominant acceptance of the Bolton route?” Rather than answer why, I believe that readers and future Coronado explorers would be better served by letting another petroleum exploration geologist explain how I decided. The late B. W. Beebe, former Vice-President of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, wrote the opening chapter of the Petroleum Exploration Handbook titled “Philosophy of Exploration":

I judiciously attempted to follow this philosophy in my quest to find the Red House and the trail of the Captain General. Fortunately I had time and capital on my side, which I fully employed to whatever extent necessary. The technical skills I brought included the Spanish language, the art of mapping, a background in exploration geology, and an understanding of human interaction with the landscape. Perhaps more important however, I had the support of those acknowledged below.

Carroll L. Riley, Brent Locke Riley, Richard Flint, and Shirley Cushing Flint must be considered the principal facilitators of this research – without them it would never have occurred. Gordon Fraser, John Blennert, Loro Lorentzen, Dan Kaspar and Marc Kaspar contributed countless hours in the field, and their efforts produced the artifacts that offer evidence of our discoveries. Durwood Ball and the staff of the New Mexico Historical Review provided the vehicle to publicize our findings to make them available to readers and researchers. Bernard L. "Bunny" Fontana, Thomas Bowen and Pearce Paul Creasman kindly provided intellectual and tangible support. Accommodating museum curators, collection specialists and archaeologists in the Southwest and the Southeast facilitated identification of the artifacts we discovered. Jack Pierce Mills and Vera Marie Burton Mills, the excavators of Kuykendall Ruins, which we consider to be Chichilticale, provided the foundation for our exploration at that paramount site. Karen Lynn Whiteside Brasher supported this adventure with love, encouragement, imagination, thoughtful criticism and hard labor. My warmest gratitude to each of you.

1. Don Burgess, “Coronado Road Shows: In Search of the Coronado

Trail,” in Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint, eds., The Latest Word from 1540: People, Places, and Portrayals of the Coronado Expedition (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, forthcoming October 2011).

2. Brasher, “The Chichilticale Camp;" Brasher, “The Red House Camp;"

Nugent Brasher, "Spanish Lead Shot of the Coronado Expedition: A

Progress Report on Isotope Analysis of Lead from Five Sites," New

Mexico Historical Review 85(1) (Winter 2010):79-81; Nugent Brasher,

"Coronado at Doubtful Canyon and on the Trail North." New Mexico

Historical Review 86(3) (Summer 2011). The permanent website is

Chichilticale.com. The site contains calendars, maps, and photographs not included in the written publications.

3. José Ortega y Gasset, Meditations on Hunting (New York: Charles

Scribner’s Sons, 1972).

4. The documents in the order I reviewed them are in: Brasher, "The

Chichilticale Camp," 464-65, n.2. There was a single exception to my

reading the original source documents in Spanish. I read the Flint’s

Italian to English translation of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s

letter to the Viceroy, 3 August 1540.

5. Richard Flint, personal communication, 2006.

6. Brasher, “The Chichilticale Camp,” 436–37.

7. The Viceroy's Instructions to fray Marcos de Niza and Narrative

Account by fray Marcos de Niza (Documents, 59-88).

8. Nugent Brasher, "The Coronado Chronicles," manuscript in possession

of author.

9. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Coronado

Expedition. Charis Wilson, Records Manager of the National Park

Service, Denver, provided me a package of documents on 14 August 2006.

10. Madeleine T. Rodack, statement at public hearing in Sierra Vista,

Arizona on 14 September 1991. In an e-mail message dated 16 January

2010, Bernard L. "Bunny" Fontana kindly provided me some personal

information about Madeleine Rodack: "Her Ph.D. was in French

literature. Before she died she translated into English Bandelier's

massive manuscript (written in French) on the history of the Southwest

that was presented to Pope Leo XIII. It's always saddened me that her

huge labor of love never saw the light of publication. I have a copy

of her manuscript. It's in seven volumes." Rodack argued

persuasively of her belief that fray Marcos de Niza arrived at

Kyakima, not Hawikku. See: Madeleine T. Rodack, "Cíbola Revisited," in

Southwestern Culture History: Papers in Honor of Albert H. Schroeder,

ed. Charles H. Lange. Anthropological Papers 10 (Albuquerque:The

Archaeological Society of New Mexico, 1985? 83?), 163-82; "Cíbola, From

Fray Marcos to Coronado," in The Coronado Expedition to Tierra Nueva:

The 1540 – 1542 Route Across the Southwest, ed. Richard Flint and

Shirley Cushing Flint, 102-15. (Niwot: University Press of Colorado,

1997).

11. Polzer, "The Coronado Documents," 36-37.

12. Juan de Jaramillo's Narrative, 1560s, (Documents, 519-24).

13. Brasher, The Red House Camp, 62 n74.

14. Brasher, The Chichilticale Camp, 436–37.

15. I intepret that Ispa is modern Arizpe, Sonora, Mexico. Castañeda

de Nájera, fol. 102r (Documents, 472).

16. Juan de Jaramillo's Narrative, fol. 1v (Documents, 520).

17. South Pass and Middle March Pass, both of which cut through the

Dragoon Mountains, are not reasonable options for the Coronado

Expedition. Lewis Spring was a location of prehistoric mezcal

production. On 10 September 1851, John Russell Bartlett camped at or

near Lewis Spring. He noted that the spot was where "the distilling

of mezcal had been carried on, on a large scale," and that "I

afterwards learned that this was the place where Papagos Indians

resorted annually to collect the Maguay, and distil the liquor…" John

Russell Bartlett, Personal Narrative of Explorations and Incidents in

Texas, New Mexico, California, Sonora and Chihuahua, 1850 – 1853, vol.

1 (Chicago: Rio Grande Press, 1965), 382.

18. I am not alone in seeking information from "native guides."

Archaeologist Stephen H. Lekson recognized the efficiency gained in

exploration by confering with locals. "Ranchers, miners, etc. should

be consulted; no archaeologist can ever know the archaeological

landscape as well as an interested rancher." Stephen H. Lekson,

Archaeological Overview of Southwestern New Mexico (final draft) (Las

Cruces,NM:Human Systems Research, Inc., 1992), 164. For a colorful

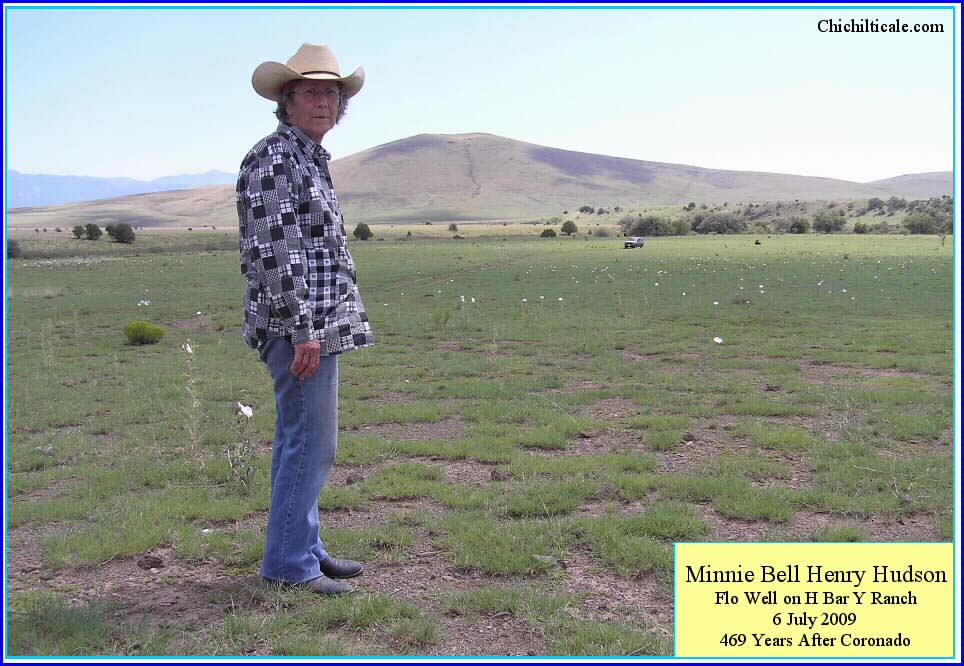

account of the life of Minnie Bell Henry Hudson, see: Minnie Bell

Hudson, Home on the Range: Her Story & Recipe Roundup (Payson, AZ: Git

A Rope! Publishing, Inc, 2006).

19. Brasher, The Chichilticale Camp, 442 – 43.

20. Castañeda de Nájera, fol. 103v (Documents, 473).

21. What I mean by "consistent with the sixteenth-century" is that an

individual artifact consistent with the sixteenth-century is one of a type that

has been found at sixteenth-century sites, and of a type that was

available during the sixteenth-century. This is not to say that the

artifact is doubtless from the sixteenth-century, rather that it could

be, that it is not in conflict with the sixteenth-century, and that it

"cannot be excluded" from the sixteenth-century. I expressed this to

archaeologist Kathleen Deagan, who responded: "I think you have it

right with 'consistent with the sixteenth-century' - there are a lot

of artifacts (most of them actually) that have a long time span that

includes the sixteenth century, and before and after (like wrought

nails or unglazed coarse earthenware)- so in the absence of diagnostic

artifacts of ONLY the sixteenth century, as well as the absence of

artifacts that definitely DON'T date to the sixteenth century, an

assemblage can be consistent with the 16th century, but not

necessarily the sixteenth century." Kathleen Deagan, Personal

communication, 2007.

22. The Blennert Sled is an innovation of John Blennert, an

internationally recognized gold and meteorite prospector and team

member. For a discussion of this technology and application, see

Brasher, The Red House Camp, 7-8, 57 n8.

23. Brasher, The Chichilticale Camp, 457, 463; The Red House Camp, 37.

24. Brasher, The Red House Camp, 54-55.

25. Vázquez de Coronado’s Letter to the Viceroy, fol. 359v (Documents,

254); Castañeda de Nájera, fol. 29r (Documents, 445). Castañeda wrote,

"El general como dicho salio del valle de culiacan en seguimiento de

su viaje algo a la ligera…" The literal translation is "the general

as said left from the valley of Culiacán in continuing his journey

somewhat a la liguera… The phrase a la liguera carries the sentiment

of "traveling light" so one can go fast. This suggests that Coronado,

concerned for food, as well as likely wanting to hurry ahead because

of his distrust of fray Marcos de Niza, partitioned the army into the

fleet footed and the slower movers.

26. Brasher, The Chichilticale Camp, 434–35.

27. Ibid., 460-61.

28. I do not explore on government land. The Douglas Dispatch

newspaper of November 27, 1967 reports that neither did Jack and Vera

Mills: “They always work on private land after securing cooperation of

the land owners, and they speak appreciatively of the interest of

these people. They do not work on state or federal land because of

the restrictions and red tape involved.”

29. Edwin R. Sweeney, personal communication, 21 August 2009: "The

papers of Gerenville Goodwin, written in the mid-1930s, contain the

place name Tsisl-Inoni-bi-yi-tu, which is the Apache name for "Stein's

Pass," or Doubtful Canyon."

30. James B. Legg, personal communication, 5 February 2009. Stanley

South, Russell K. Skowronek, and Richard E. Johnson, Spanish Artifacts

from Santa Elena, Anthropological Studies, 7, Occasional Papers of the

South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology (Columbia:

University of South Carolina, 1988), 44-45; Jennifer M. Hamilton and

William H. Hodges, "The Aftermath of Puerto Real: Archaeology of

Bayahá," in Puerto Real: The Archaeology of a Sixteenth-Century

Spanish Town in Hispaniola, ed. Kathleen Deagan (Gainesville:

University Press of Florida, 1995), 409.

31. Nugent Brasher, "Spanish Lead Shot of the Coronado Expedition: A

Progress Report on Isotope Analysis of Lead from Five Sites," New

Mexico Historical Review 85 (winter 2010):79-81; Brasher, "Coronado at

Doubtful Canyon." Eugene Lyon, personal communication, 17 October

2009. For a discussion and photographs of estoperoles see South, et.

al., Spanish Artifacts from Santa Elena, 34, 39-40, 44-45, esp. 57-58.

32. Juan de Jaramillo's Narrative, fol. 1v-2r (Documents, 520).

33. Data used for generation of Map 2 kindly provided from a custom

extraction by Karyn de Dufour from the Archaeological Records

Management Section (ARMS) Database, New Mexico Historic Preservation

Division, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 5 November 2004.

34. Juan de Jaramillo's Narrative, fol. 1v (Documents, 520).

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid. A discussion of the "swollen" Río Balsas is appropriate.

Recall that Melchior Diaz traveled as far north as Chichilticale, but

did not go forward because of snow in the winter of 1539-1540, AGI,

Justicia, 267, N.3, Testimony of Juan de Zaldívar, Guadalajara, August

2, 1544, fol. 91r, transcribed and translated in Great Cruelties, 262.

Winters were cold during the time of the expedition. Castañeda

reported heavy snow beginning in October 1540, and the Rio Grande

frozen almost four months during the winter of 1540 - 1541, Castañeda

de Nájera, fol. 56r, 63v, 75v (Documents, 455, 458, 462). Consider the

journey of the Advance Party using the modern calendar. They camped

at Hidden Valley on 4 July 1540 and crossed the Gila River the next

day. On the morning of 9 July they crossed the Río Balsas (San

Francisco River). On the morning of the 11 July they crossed the San

Francisco River (Río Balsas) again, but well upstream. The relevant

question is "What caused the swollen river of 9 July?" Recall that

Melchior Díaz halted because of snow the previous winter. Could the

high water have been snowmelt? This is unlikely because the same

conditions would have prevailed at the Gila River – Hidden Valley

crossing. It is more likely that the high water was monsoon rain that

brought the river up, but stopped short of a flood in the current

local sense of the word. "High water" may be a better description.

Floods at Alma are almost always caused by rain on snow that melts the

snow and sends melt water down all at once. If the swollen Río Balsas

was this type of flood, then the Coronado expedition could not have

crossed for days. Moreover, July is not when this kind of flooding

occurs. Summer has no floods, just high water, especially if snowmelt

is still flowing in the river when the monsoon starts. A monsoon rain

on a river with snowmelt could have created a river that appeared

flooded to Jaramillo, but would have been only "high water" to

contemporary Alma locals.

37. I exclude the Blue River as a likely Coronado expedition route

because it effectively flows through a box canyon. Archaeologist

Walter Hough described the river in 1907: "The Blue River runs in its

narrow canyon… There is abundant water in this valley… Although the

valuable farming land was limited the pueblos are, in the main, large

and from various evidences were long inhabited." Walter Hough,

Antiquities of the Upper Gila and Salt River Valleys in Arizona and

New Mexico, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 35 (Washington:

Smithsonian Institution, 1907), 42.

38. Hough described Pueblo Creek as "a small stream flowing southeast

through very broken country… Its valley furnishes no agricultural

land, and it is probable that the evidences of habitation there

indicate only a temporary or periodical occupancy for ceremonial

observances or for hunting…" Hough, Antiquities of the Upper Gila and

Salt River , 57-58.

39. Juan de Jaramillo's Narrative, fol. 2r (Documents, 520).

40. Evidence of a multi-day camp at the Río Frio is offered by the

papers associated with disposal of the Juan Jiménez estate. These

include a legal document wherein Rodrigo de Trujillo described the

Coronado expedition at the Río Frio campsite on 9 April 1542 (Julian)

(Sunday, 19 April 1542 Gregorian) as “being alojado [if a military

usage, then “quartered”] on the ribera [area close to the edge of a

river] of the river that is called the Río Frio that is between

Chichiltiqueale and Cibola;” AGI, Contratación, 5575, N.24, Disposal

of the Juan Jiménez Estate, 1542 [copy, 1550], transcribed and

translated as Document 27 in Documents, 373; Hough, Antiquities of the

Upper Gila and Salt River Valleys, 12, 70, 73; Victoria D. Vargas,

Copper Bell Trade Patterns in the Prehispanic U. S. Southwest and

Northwest Mexico, Archaeological Series 187 (Tucson: Arizona State

Museum, 1995), 93, 96.

41. Juan de Jaramillo's Narrative, fol. 2r (Documents, 520).

42. Brasher, “The Red House Camp," 46-47.

43. The diario of José de Zúñiga offers information useful in

contemplating the Coronado route. From near Gatlin Lake and Cerro de

Mula, it is about ten miles north over plains to the lava flows at Red

Hill. This setting fits the Zúñiga report that “At sunrise [29 April

1795] I undertook my march, course to the north, and walking through

some plains, after about three leagues, we crossed a sexa of malpais…”

Malpais is lava on the surface, and the only such place in the region

is at Red Hill cinder cone. In an e-mail message on 23 August 2007,

Richard Flint provided his interpretation of the Spanish word sexa:

"Probably the word is "ceja," which is used frequently in

geographical/topographical contexts to refer to a surface stratum of

rock visible in an escarpment that is usually significantly different

in color from the underlying rock strata. More generically, it can

refer to a cliff or steep bedrock face of any sort." I responded that

same day: "The lava flow at Red Hill forms an escarpment of BLACK rock

sitting on WHITISH Colorado Plateau bedrock. The contrast is striking

– this is the only place such occurs along the route most likely

followed by Zuniga." The word ceja most commonly means eyebrow; the

Red Hill lava flow is so shaped. I believe that Coronado and Zúñiga

traveled much of the same trail, with an important exception being

that Zúñiga departed Coronado's trail at the Red Hill cinder cone and

lava flow near modern Red Hill, New Mexico. Zúñiga wrote that after

crossing the "sexa [ceja] de malpais" (eyebrow-shaped flow of lava

rock), and bearing to the north-northeast, he reached Zuni Salt Lake,

which he described as "very beautiful salt flats with footprints and

trails headed in various directions." From there Zúñiga continued to

Halona (modern Zuni), arriving from the southeast. Following his stay

in Halona, Zúñiga departed to the southwest, and reaching Hawikku, he

would have rejoined Coronado's presumed route. José de Zúñiga, “Una

expedición militar de Tucson (Arizona) a Zuñi (Nuevo México),” in La

España ilustrada en el Lejano Oeste: viajes y exploraciónes por las

provincias y territorios hispánicos de Norteamérica en el siglo XVIII,

ed. Amando Represa. Estudios de historia (Valladolid: Junta de

Castilla y León, 1990), 94-95. The boulders at Dangerous Pass were described by an Advance Party member: Pedro de Ledesma, Eleventh de oficio Witness, "A Transcript of the Testimony" in Richard Flint, Great Cruelties Have Been Reported (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 2002), 243-45.

44. Brasher, The Red House Camp, 53-55.

45. Vázquez de Coronado's Letter to the Viceroy, fol. 360v (Documents, 256).

46. Richard Flint, personal communication, 21 August 2009.

47. Good prospecting practice demands that all evidence be presented,

regardless of how flimsy it might initially appear. Rancher William

French reported that "Indian heiroglyphics scratched on the rocks in

the box-canyon [located] about a mile and a half [upstream along the

Rio San Francisco] above the ranch [house at Alma]… consisted mainly

of rude imitations of tents, fish and what might be considered turkey

tracks." Being as I consider Alma to be the site of the Río Balsas crossing, the mention of heiroglyphics of tents, possibly inspired by oral histories of Coronado tents, attracted my attention, so we plan to investigate the box when the water level and vegetation permit. William French,

Some Recollections of a Western Ranchman: New Mexico, 1883-1899 (New

York: Sentry Press, 1965), 41.

48. Richard Flint, personal communication, 9 September 2006.

49. Jerome J. Pratt, Retired Volunteer, Wildlife Management

Consultant, Desert and Island Ecology, "Comment: Coronado National

Trail Study," Public Review Draft. Unpublished proceedings, June 1991.

50. Nicoló Machiavelli, The Prince (New York: Washington Square Press,

1963), 22.

51. B. W. Beebe, "Philosophy of Exploration," in Oil Is First Found in

the Mind: The Philosophy of Exploration, ed. Norman H. Foster and

Edward A. Beaumont. Treatise of Petroleum Geology, No. 20 (Tulsa:

American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 1992), 143.