The Francisco Vázquez de Coronado Expedition in

Tierra Doblada

The 2013 Report on Artifacts and Isotopes of the Minnie Bell Site at Big Dry Creek, Catron County, New Mexico

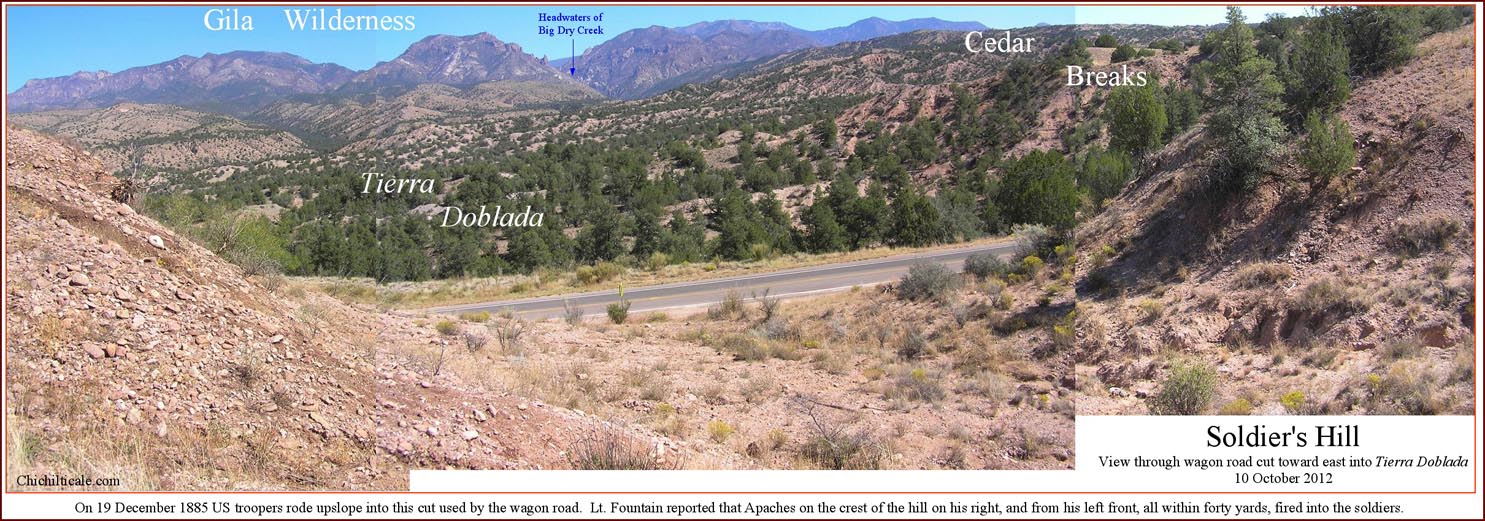

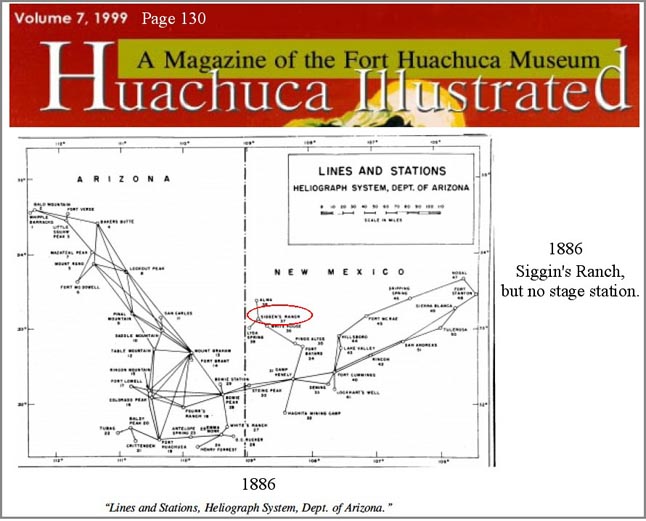

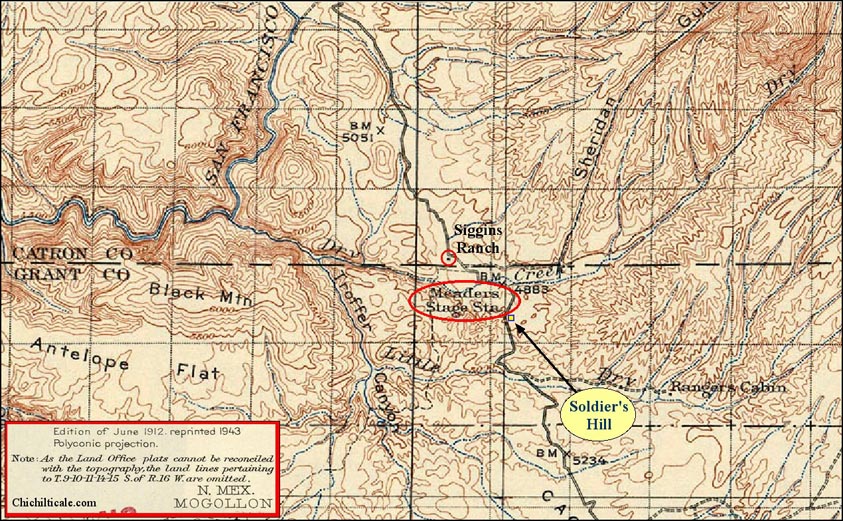

The Apache bullet struck Dr. Maddox in the chest, smacking his commanding figure off his big buckskin horse. Two troopers tried to drag him to cover, but another bullet blasted through the back of his head, exiting at the corner of his mouth, leaving a jagged scar, ending his life. The surgeon had been amongst the leaders in a troop of seventeen soldiers that had just departed their camp at Big Dry Creek when the ambush began with a volley of shots that killed four soldiers, several horses and mules, and the doctor. The tragedy began and ended suddenly that frigid December morning in 1885, and in the confusion the Apaches managed to loot the arms and ammunition of the dead before escaping into up-and-down terrain impossible for pursuit by the soldier’s horses. The dead men were gathered and carried to the nearby Siggins ranch house. The horse and mule carcasses were rolled over the edge of the road, where they froze, dried, and finally withered away, the skeletons remaining for years, creating a white landmark to point at when tellers recounted the tale of the waylay.

More than a half-century after the ambush, a seven-year-old girl picked up some of the spent casings left by the Apache rifles. “There’s history here,” said the gentle man who had shown her the ambush site. And there was, and it was even more than either of them knew – for some 400 years earlier a Spanish Captain General may have also stood at that very spot. This is the story of Coronado at Big Dry Creek.(1)

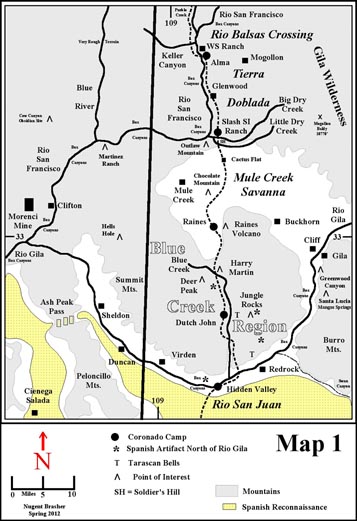

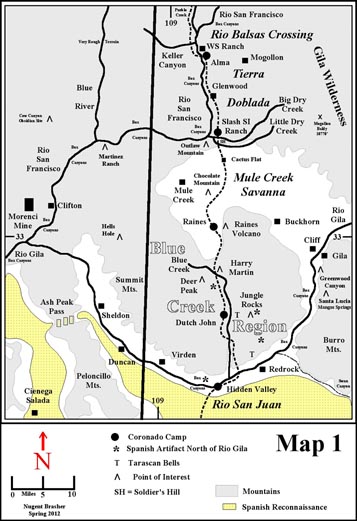

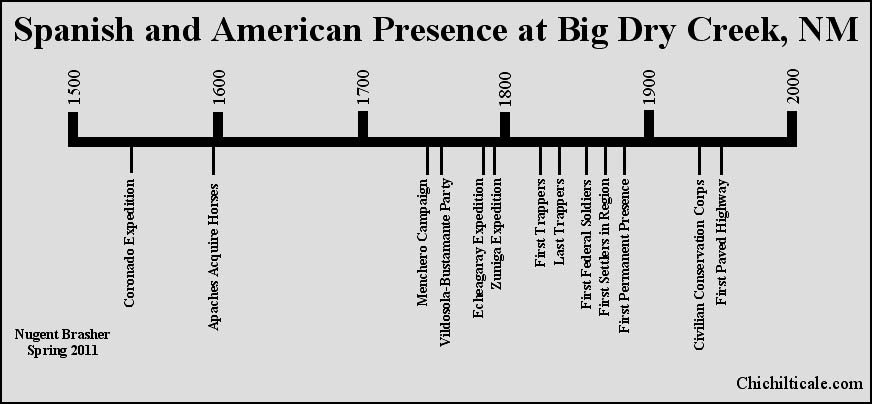

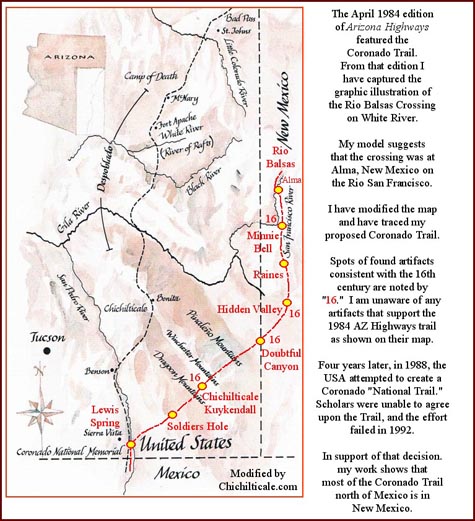

Beginning in the summer of 2009, my exploration to determine the route of Capt. Gen. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado focused on the trail between the Río Gila in New Mexico on the south and Alma, New Mexico on the north.(2) Of this portion of the route, Juan "El Mozo" Jaramillo, horseman in the 1540 advance party of the Coronado Expedition, recollecting some twenty years after the fact, offered the only description of the northbound Coronado Trail along that trace.

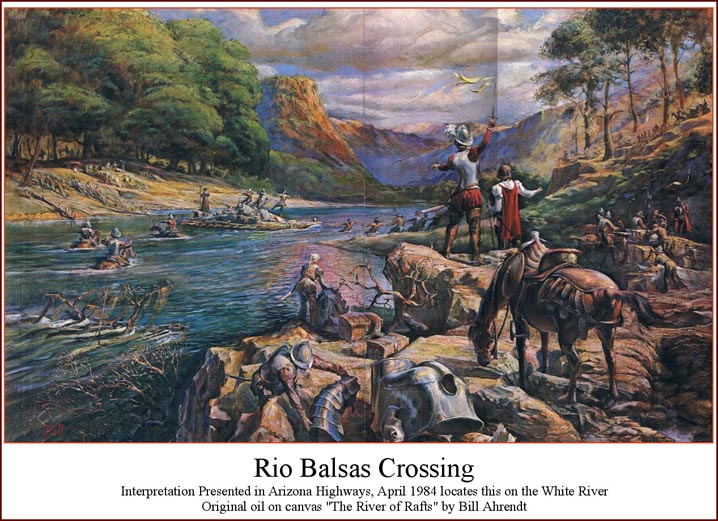

“After leaving here [Río San Juan] we went to another river, by way of land somewhat uneven [doblada], moving more to the north. The river we named Las Balsas because we crossed in rafts because the river was swollen. It seems to me that we took two days from one river to the other, and this [uncertainty] I say because it has been so long since that happened to us that I could be mistaken in some days…”(3)

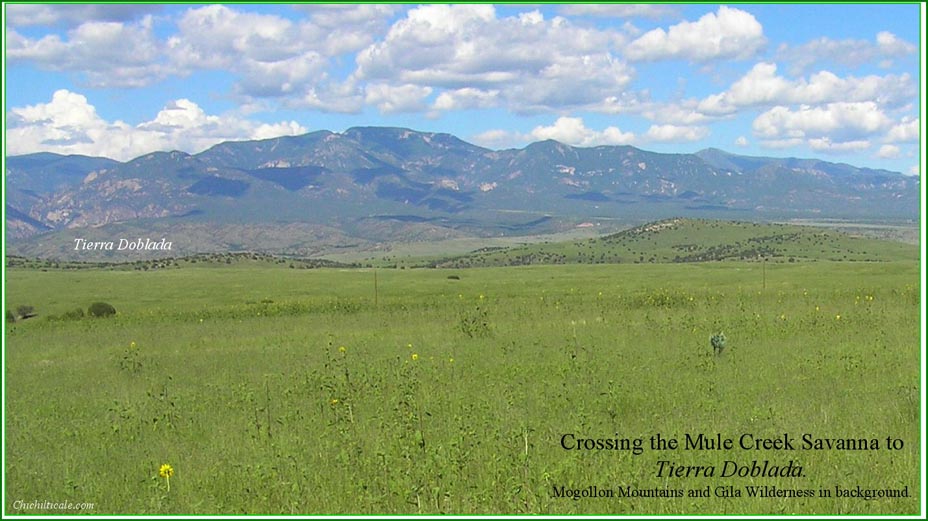

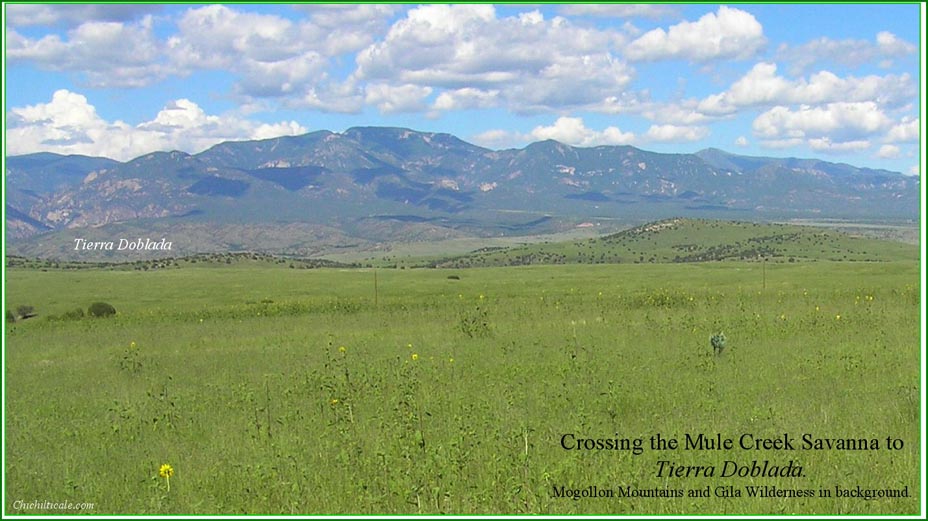

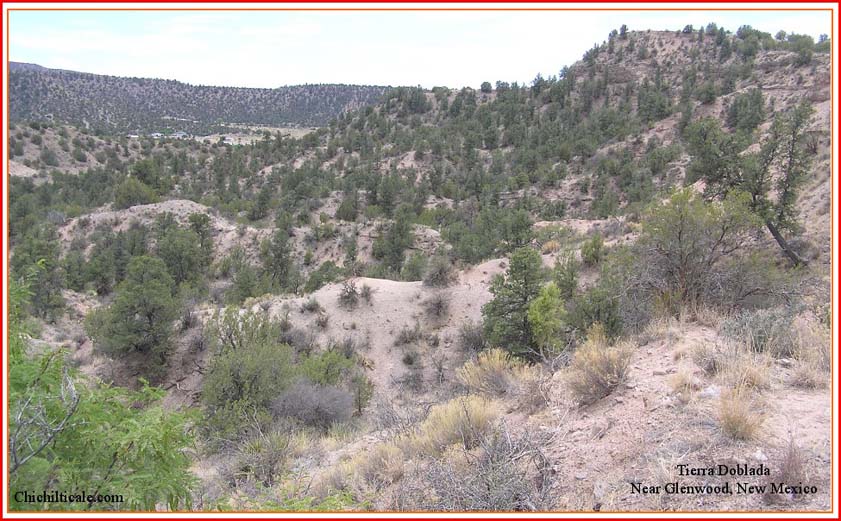

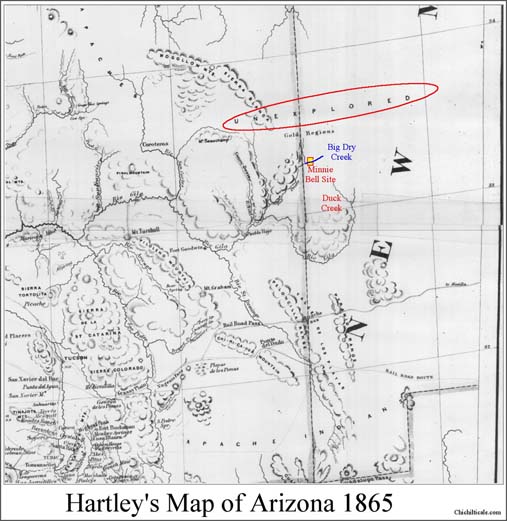

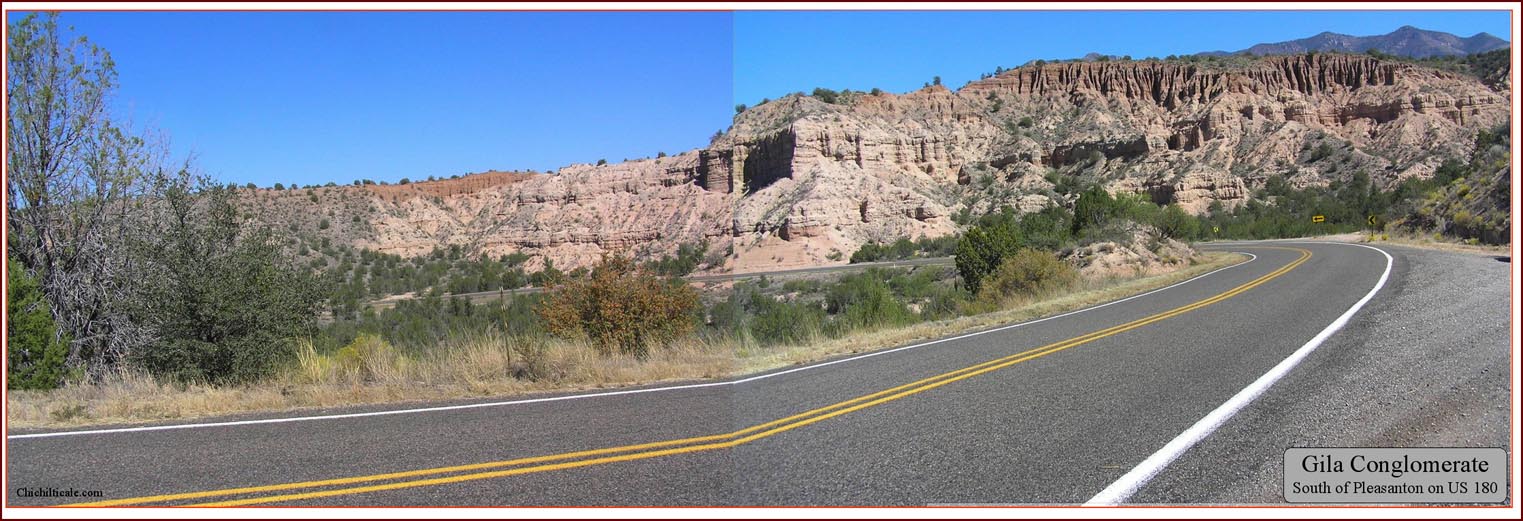

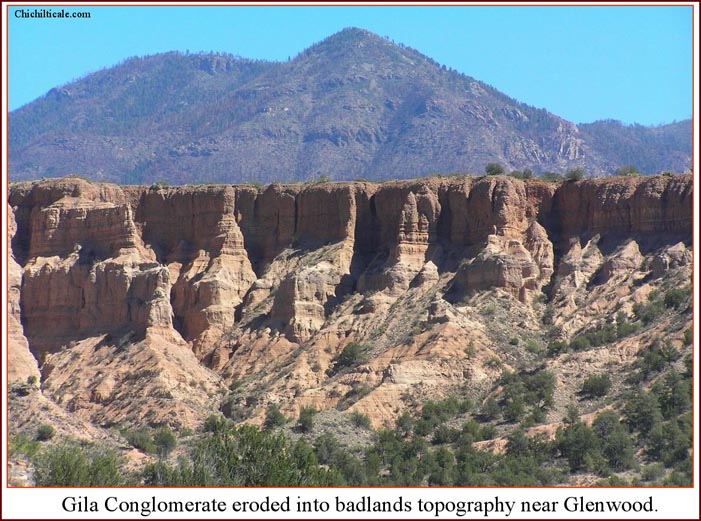

I interpret this passage to be Jaramillo's recollection of the landscape between the modern Río Gila (Río San Juan of Coronado) at Hidden Valley, New Mexico and the modern Río San Francisco (Río Balsas of Coronado) at Alma, New Mexico. One stretch of this proposed northbound Coronado Trail passes around Chocolate Mountain, then crosses the flat Mule Creek savanna to Little Dry Creek, the southern edge of what Jaramillo called the tierra doblada, and what pioneer ranchers refer to as the Cedar Breaks. This tierra doblada, up-and-down or doubled-over terrain, was caused by extreme erosion creating deep cuts in the landscape. The scarcity of flat land causes travelers to continually climb and drop, to move up-and-down more than along a lateral course.(4)

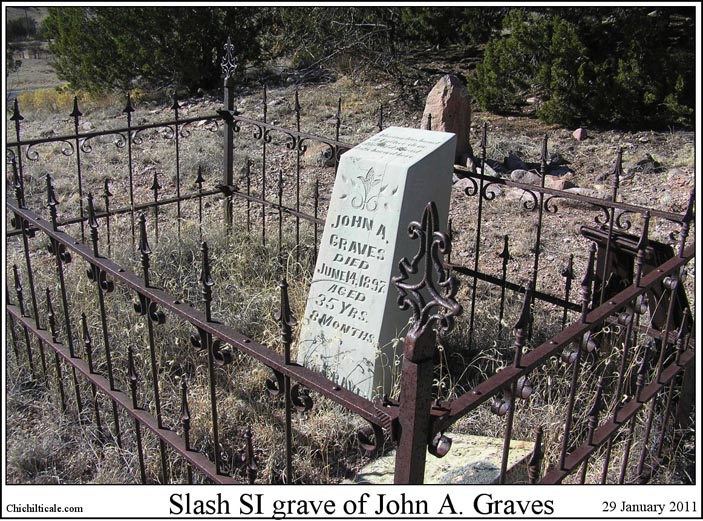

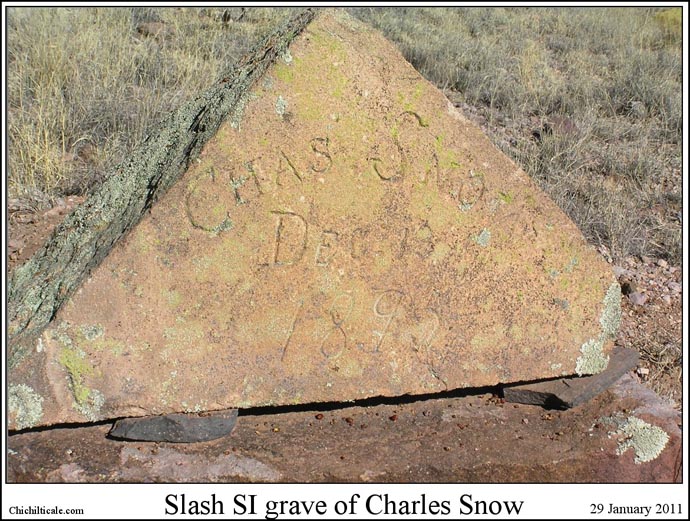

My proposed trace of Coronado's route through the tierra doblada suggested a campsite at Big Dry Creek on the historic Slash SI Ranch. Beginning in June 2010, our exploration team focused on this prospect, and we discovered convincing material evidence of the expedition there. Following my established custom, this account will present only heretofore unpublished material, so readers are directed to my earlier reports for background. This report is intended to provide information about field exploration from June 2010 through May 2011, and is current to March 2013.(5)

On 20 June 2010, Big Dry Creek landowner Kenny Sutton and I conducted a "swing-stick" (handheld) metal detector reconnaissance near the historic Slash SI Ranch headquarters. The test site was selected based on surface geology; subsequently Sutton arranged permission to explore on the private land. Sutton found an 8.5 cm long, quadrilateral, iron awl buried directly beside a Mimbres black-on-white potsherd. I considered the June experimental metal detecting successful in showing that the terrain could be effectively explored in such a manner, so I obtained landowner permission to conduct a wide-ranging field study.

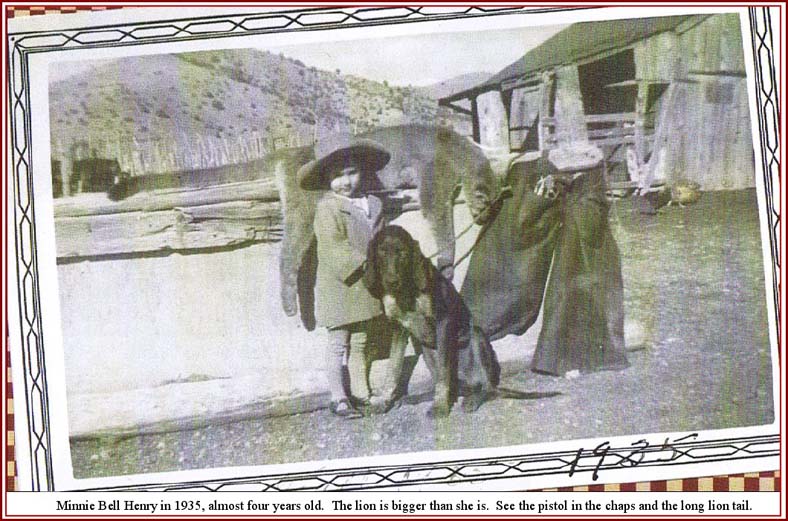

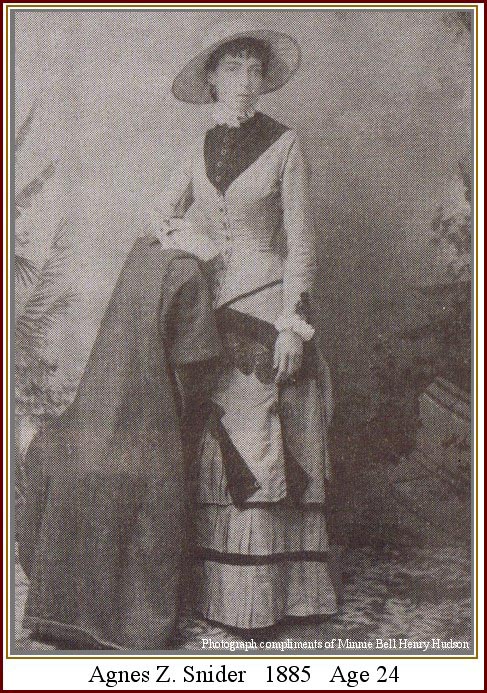

Native pioneer and author Minnie Bell Henry Hudson, daughter of James and Violet Henry, was two years old when she arrived at the Slash SI Ranch headquarters in 1933. She lived on that property and adjoining property until 1990, when she sold her historic ranch and moved to a nearby property on private land at Cactus Flat, her present home. Beginning in October 2010, Minnie Bell, for whom this site is named, and how she will be respectfully recognized throughout this report, tirelessly and resolutely began to guide me through the landscape of her lifetime, where she rode a horse, worked cattle, and followed striker hounds. She was authoritative in locating known historical sites recorded in written and oral history, such as Soldier's Hill, and notable homesteads and landmarks, and in tracing the extinct trails and roads, and in guiding me to places that could only be known by a native. Her immeasurable contribution elevated my confidence in our conclusions.(6)

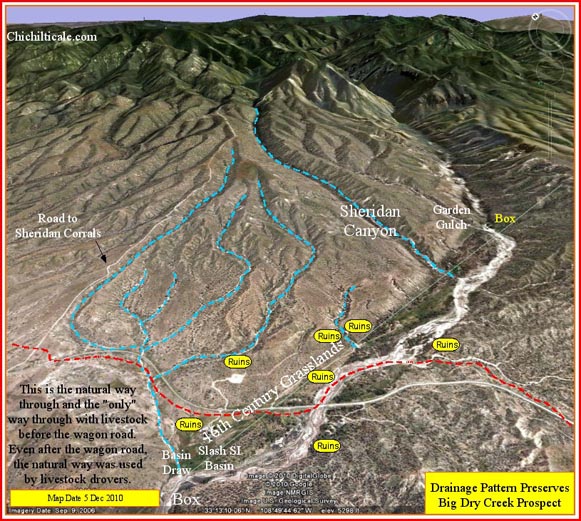

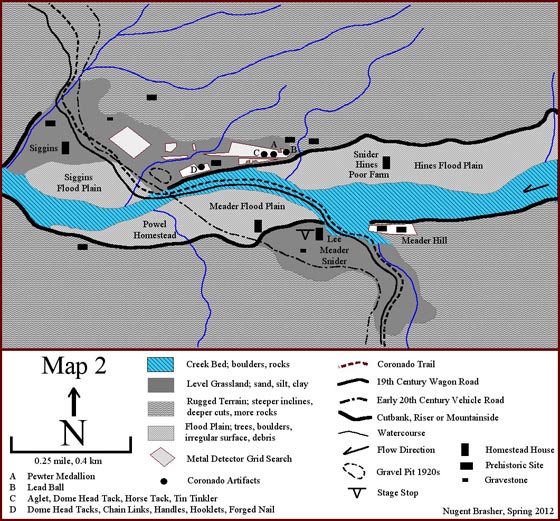

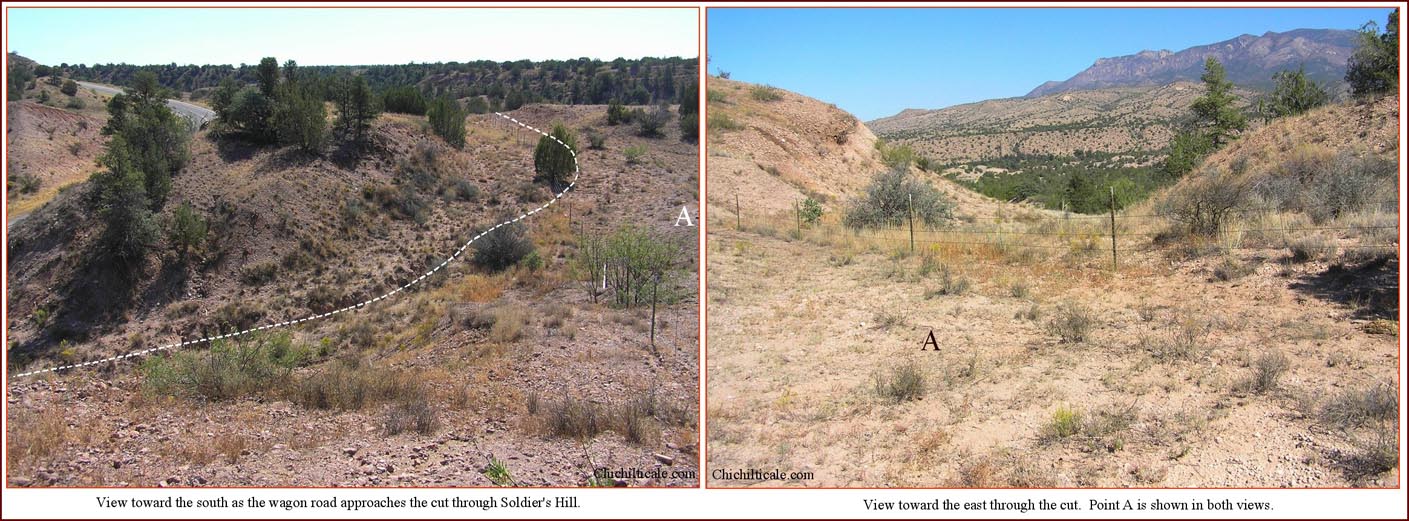

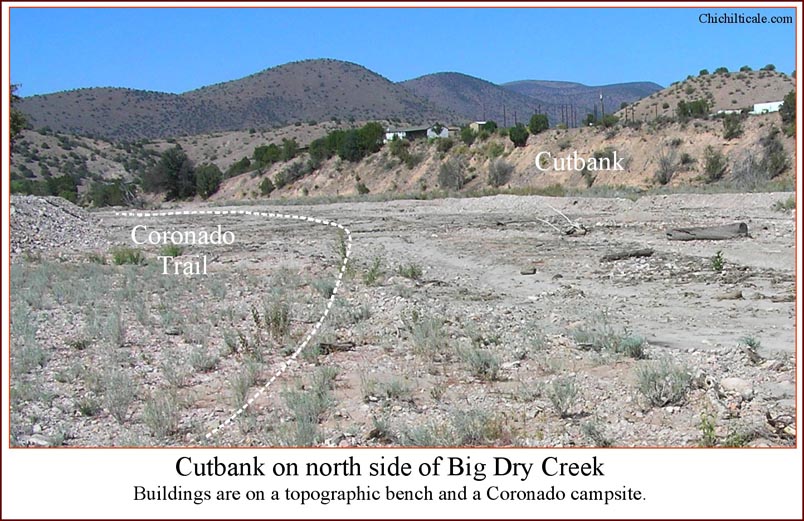

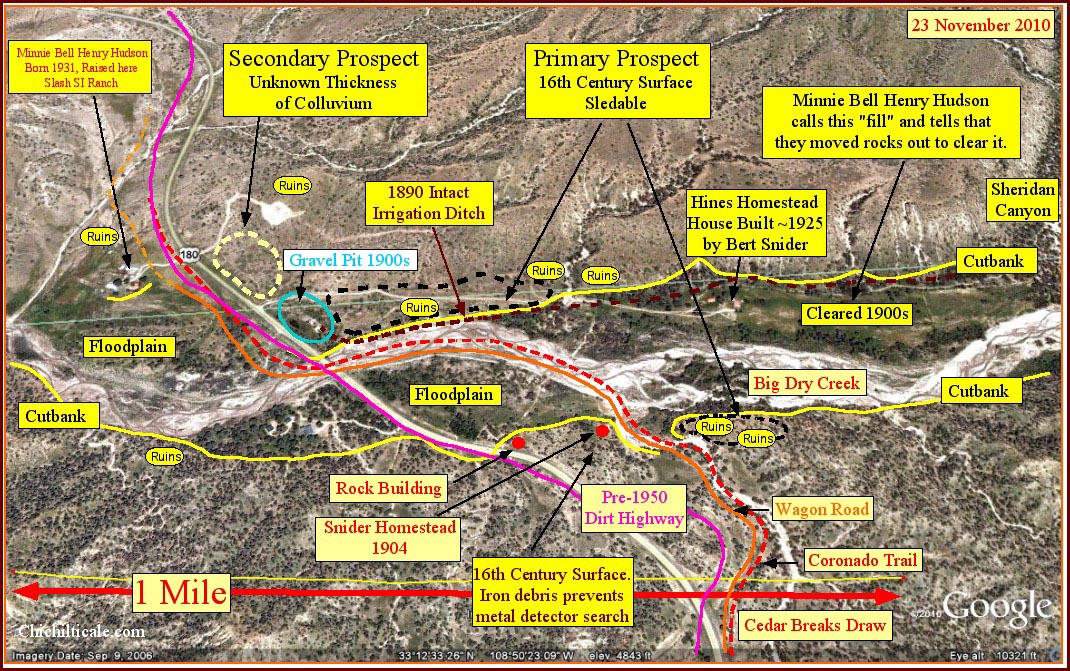

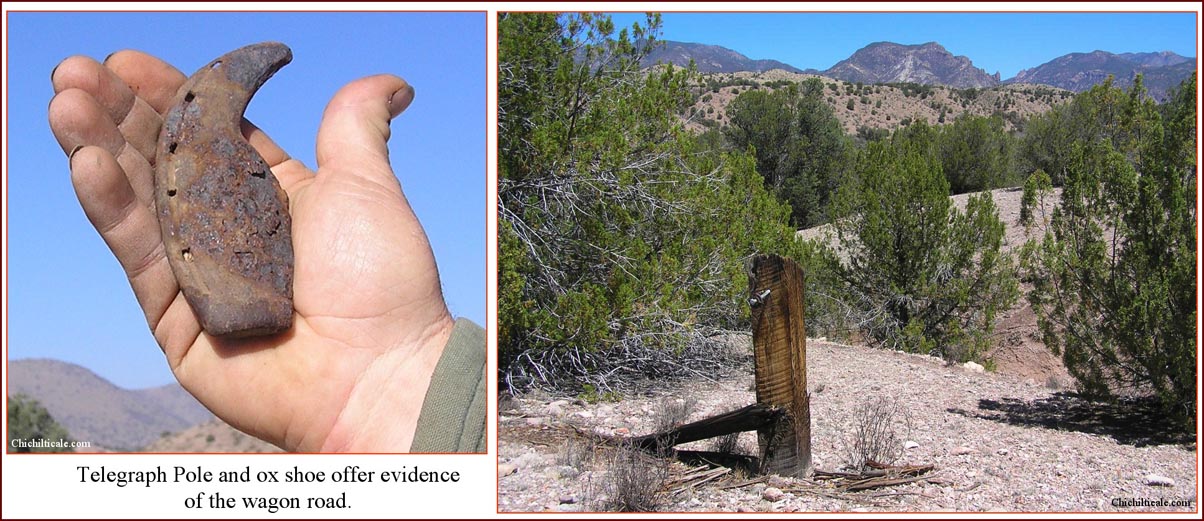

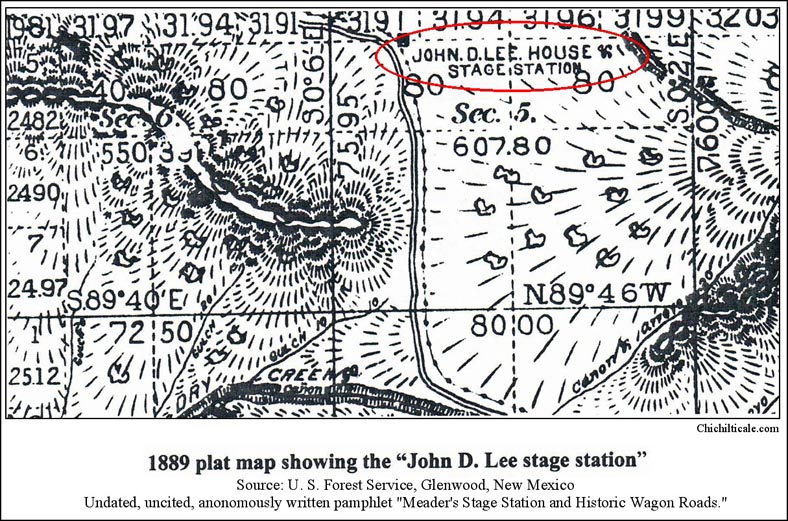

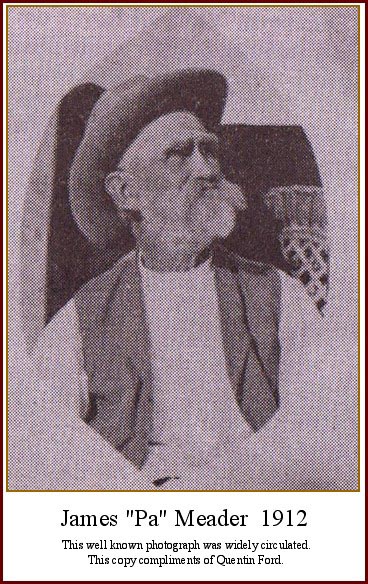

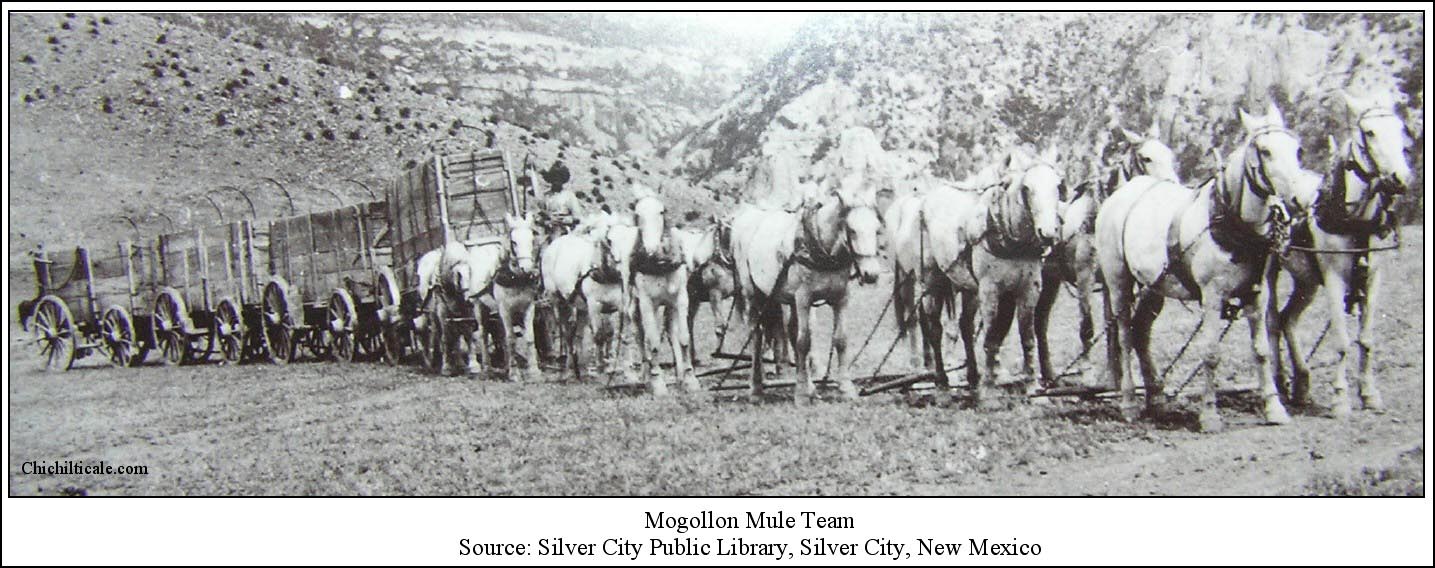

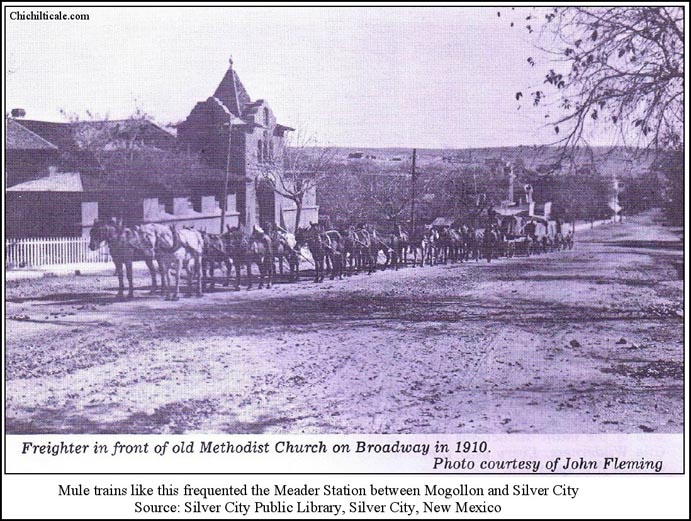

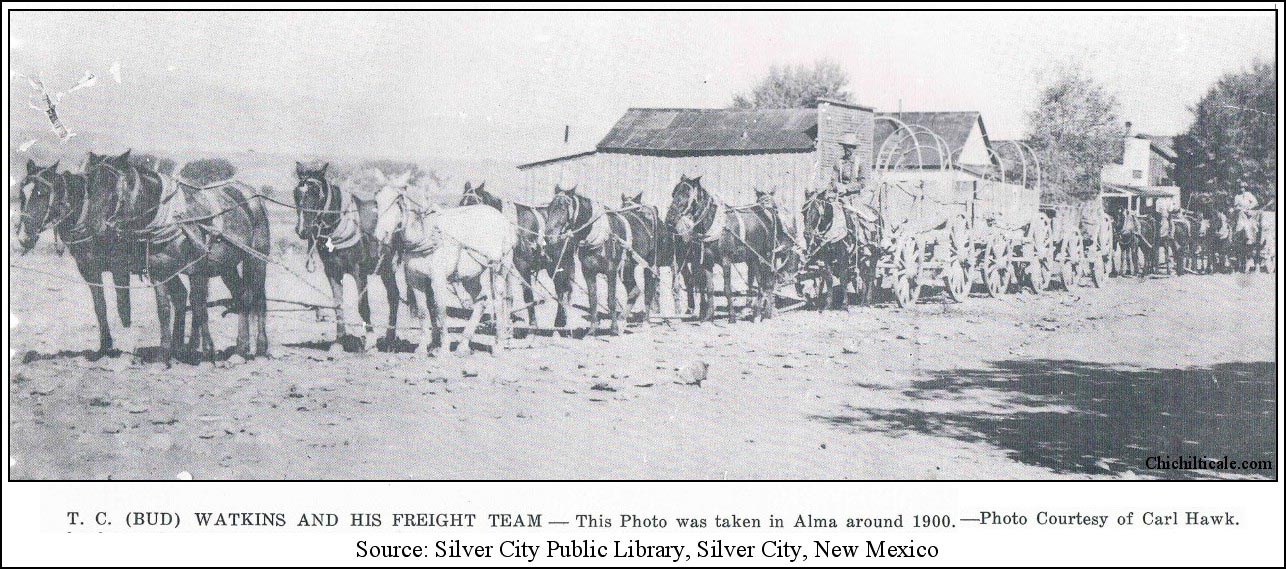

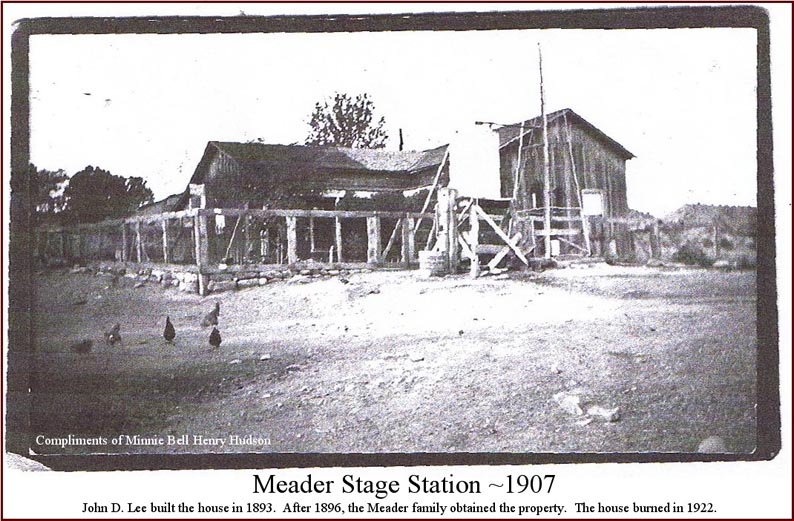

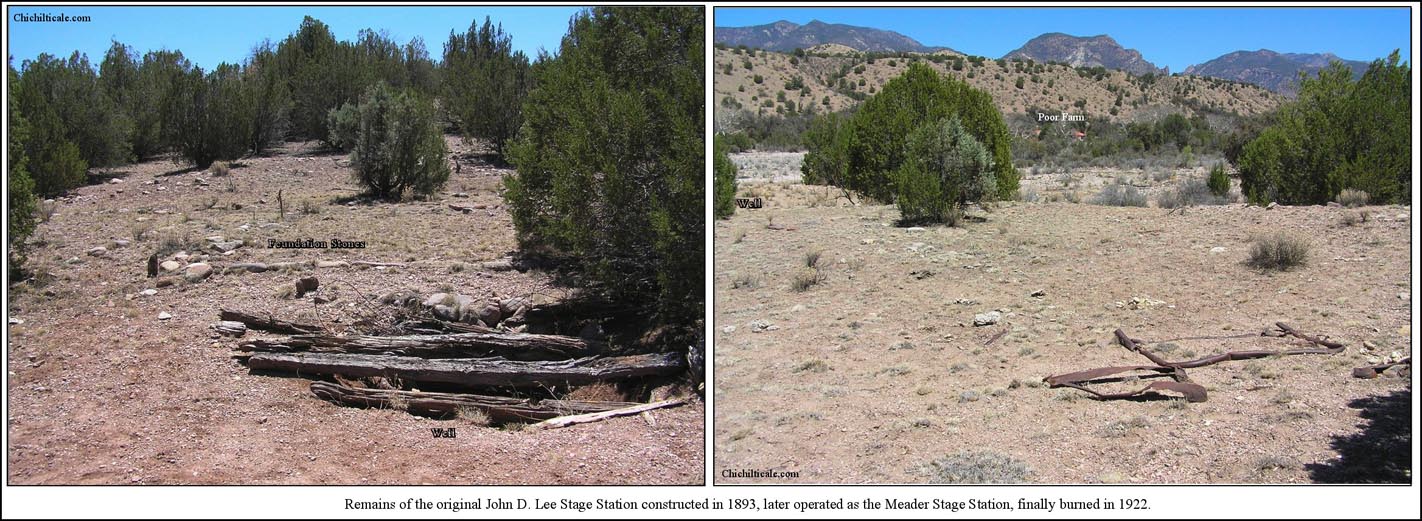

One of the team’s first tasks was to trace the most likely route of Coronado’s entry into the Cedar Breaks to reach Big Dry Creek. From Minnie Bell I learned that four roads through the Breaks had existed at various times. The wagon road was the earliest, except, of course, for the pre-historic foot trail. Along many stretches, the foot trail offered a suitable trace for wagons and livestock, so the trails lay together. The wagon road was also used by the first automobiles that appeared in 1907. Next in decreasing age was the unpaved motor vehicle road completed in the 1920s, its course closely aligned with the wagon road. Then came the first paved road for vehicles, built in the early 1950s, and, afterwards and finally, the modern paved highway, constructed in the 1990s. I hypothesized that Coronado in 1540 might have followed the route of the 350-year later wagon road through the Breaks, especially if that trace followed the path of least resistance for livestock. Beginning on the south where the route passed through a natural cut to “fall off” into the Breaks, the northbound wagon road descended into a basin of rugged terrain and eventually reached a small flat above the flood plain on the south side of Big Dry Creek and on the west side of Cedar Breaks Draw. Beginning in the 1880’s, first the Lee, and then the Meader wagon and stage stop occupied the flat. There the northbound wagon road entered Big Dry Creek and turned downstream to the west, passing beneath a steep cutbank on the north until it reached the terminus of that cliff, where the road ascended a gentle rise to the north bank of the waterway. From there the trace crossed level land to the historic Slash SI Ranch headquarters, founded in the early 1880’s, and on northward to the rim of the basin, where it ascended through a natural cut to "rim out" on the higher flats.(7)

The northbound wagon road followed an "only" trail – it entered the southern end of the basin through the only traversable natural cut and it traced the only semi-level route through the rugged terrain squeezed between the towering Mogollon Mountains on the east and the sheer walls of the Río San Francisco canyon on the west. The exit of the northbound wagon road did not, however, use the natural cut on the north side of the basin. Instead it used a manmade slope; antecedent or subsequent livestock herds, which always used the natural cut, did not use this artificial grade. With the exception of the exit, the northbound wagon road, like the Coronado Trail at its Río Gila (Río San Juan) and Río San Francisco (Río Balsas) crossings, offered the only practical way through for parties driving livestock.

The prehistoric foot trail and the wagon road are together at Big Dry Creek, where exists an attractive campsite. The abundance of chipped, black obsidian on the north bank topographic bench of the creek indicates a prehistoric Indian camp, and the several nearby pithouse and masonry ruins, some containing potsherds, suggest a permanent, or at least a seasonal, occupation site. Like the Indians before, stage station operators Lee and Meader, rancher Siggins, and Federal soldiers recognized the Big Dry Creek spot as a building location and campground. We have found evidence that Coronado almost certainly saw a good campsite there.(8)

Exploration Model at Big Dry Creek

Most archaeological solutions begin with a geoarchaeological problem. Of foremost consideration was to determine where a sixteenth-century surface remained undisturbed and available to metal detector exploration. Using field reconnaissance, satellite imagery of the landscape, and topographic mapping, I developed a geological model that emphasized the locations of sixteenth-century surfaces, as well as provided a prediction of where sixteenth-century surfaces are only slightly covered with more recent sediments.

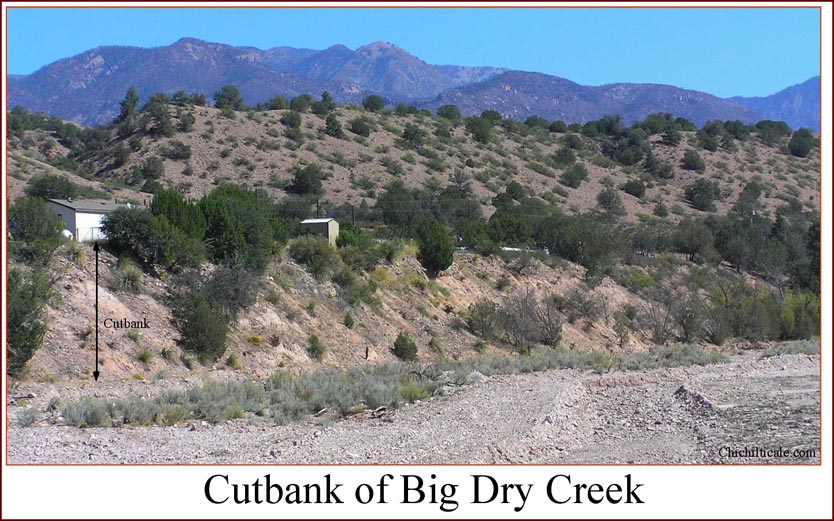

The geology of the Slash SI Ranch Prospect is dominated by Big Dry Creek. The cutbanks of the creek define the water corridor that contains stream channels and floodplains. Sixteenth-century campsites that would have been subsequently cut by stream channels or covered by flood plain sediments are unlikely to contain artifacts that can be detected and recovered – the artifacts have been either transported away or buried beyond metal detection depth. Respecting that efficient exploration should avoid prospects that have a high risk of failure, we recognized that initial prospecting should focus on areas outside the water corridor. Such surfaces include mountainsides and benches above the cutbanks. Mountainsides are not favorable campsites or artifact containers because of rugged, rocky terrain and irregular surfaces cut by drainage. Geomorphic benches are favorable campsites and artifact containers because they are level and have not been covered by thick colluvium from the mountainsides or cut by drainage. Benches offer the most favorable prospecting surface on the Slash SI Ranch prospect.

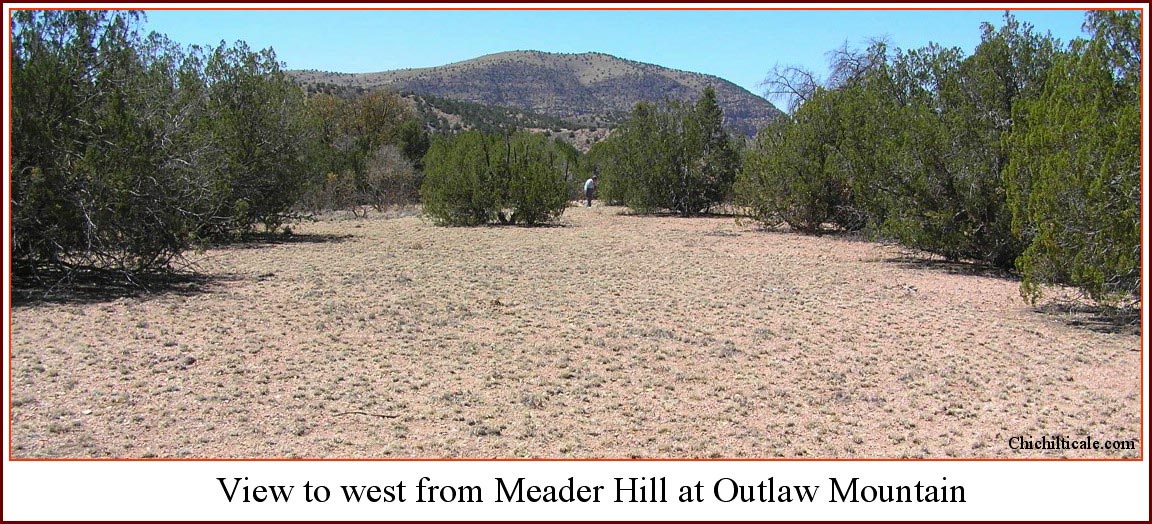

The most prospective sixteenth-century surface at the Slash SI Ranch prospect is on a geomorphic bench on the north side of Big Dry Creek. This bench is bounded on the south by the northern cutbank of the creek, on the east by the Hines floodplain, on the west by the Siggins floodplain, and on the north by the mountainside. This surface has not been flooded, and has been only slightly eroded by wind and rain since the sixteenth-century. Such conditions are conducive for cultural material to be at or near the surface. There are two additional sixteenth-century surfaces of interest in the prospect. The stage station was built on a geomorphic bench favorable to preserving Coronado-era artifacts. Unfortunately, effective metal detector exploration on that surface is severely impeded by copious amounts of metallic homesteader debris. East of the stage station is flat-topped Meader Hill, where ruins of a masonry building and numerous obsidian chips are present. Although the hilltop is not directly beside a water source, it is nevertheless a favorable campsite because of vantage, fuelwood, shade, and level, soil-covered ground. The landform is advantageous to retaining sixteenth-century material because of lack of deposition or fluvial erosion of that surface. We considered Meader Hill a worthy prospect.

Coupled with the geological model, I used the historical information presented in the following section to develop a human-presence model consisting of trails, campsites and prehistoric ruins. Then I turned toward consideration of the Coronado travelers themselves. As I reconstruct events, the following army of the Coronado Expedition reached Big Dry Creek via the subsequent 1800s wagon road alignment. The travelers turned downstream and reached the western end of the cutbank near the 1900s gravel pit. There they turned north, climbing out of the creek. The time to initiate camp selection for northbound expeditionaries was after the travelers ascended from the creekbed and looked around. They saw grasslands on level terrain all around them. Water flowed and pooled in the creek.

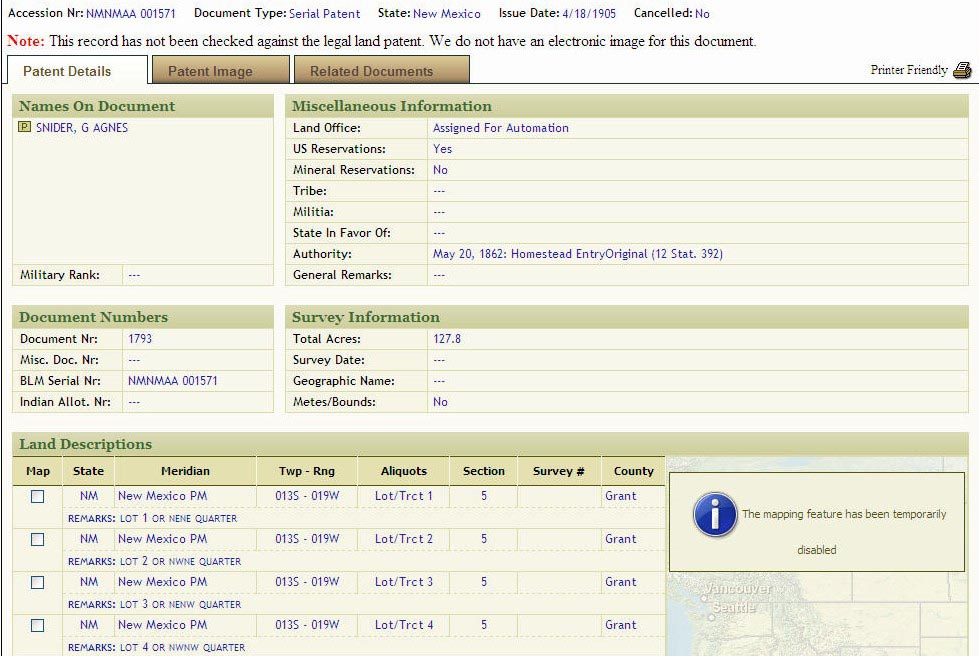

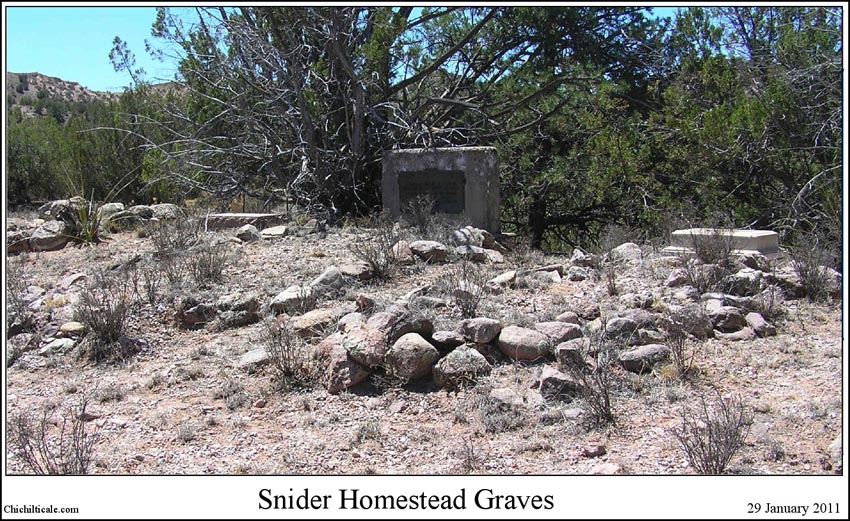

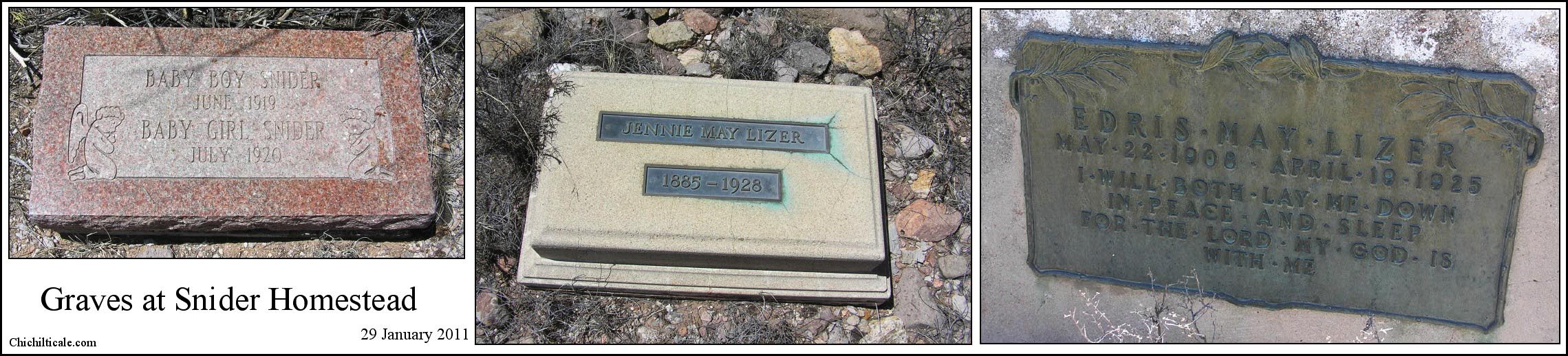

As more travelers arrived, word spread that the campsites south of Big Dry should be used because northern camps were occupied. This put Coronado expeditionaries on the future stage station and Snider homestead sites, and in the grasslands along and near Cedar Breaks Draw nearest Big Dry Creek. Some travelers selected the flat top of Meader Hill and others camped in the water corridor of Big Dry Creek. Farriers might have chosen the creekbed because of the water and firewood they required. Almost all travelers would have used the creek for livestock and human water consumption. The southbound retreating army would have selected similar campsites, using perhaps even more spots along Cedar Breaks Draw than had the following army.

Employing these geological and human-presence concepts, I generated an exploration model that directed the initial focus of our search – we first looked on surfaces that were little altered since 1540, such as land that had not been eroded or flooded, and at places on this surface that best fit my instinct and considered notion of where campsites for large groups might have been located.

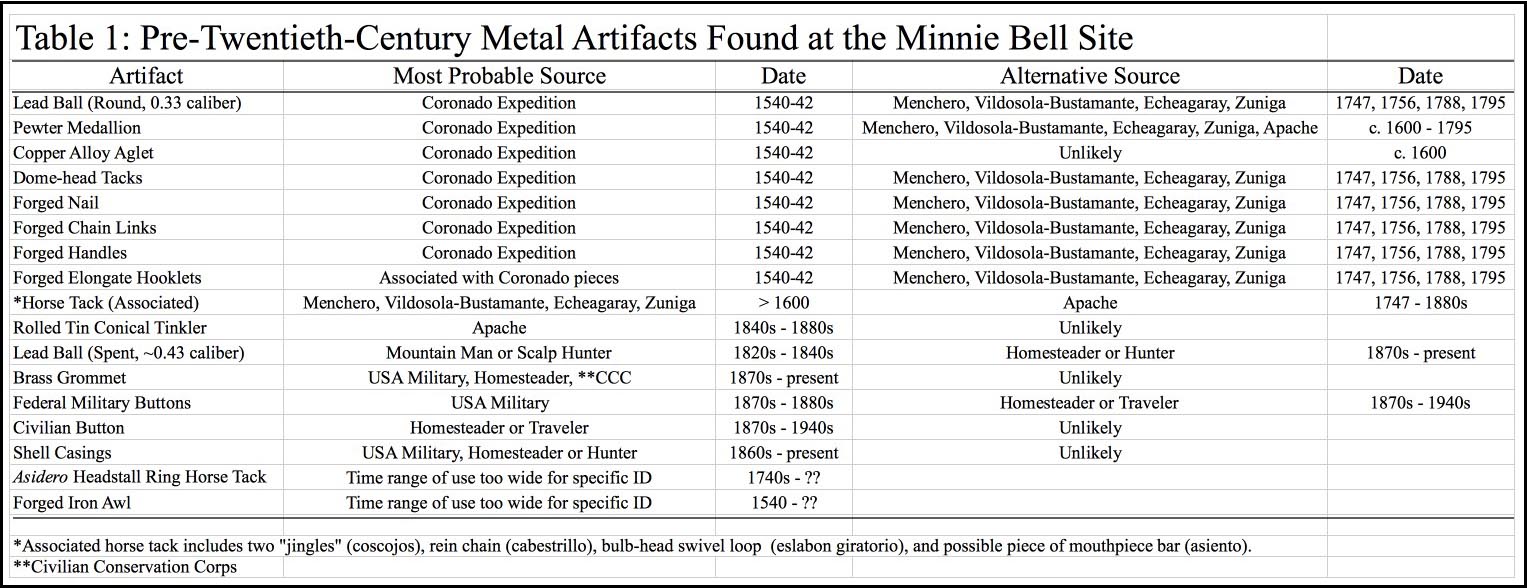

Artifact identification demands an historical framework. Using the results of historical research, I will provide a chronology of presence in the region. This will demonstrate that Native Americans, Europeans, Mountain Men, scalp hunters, Federal soldiers and American settlers were at Big Dry Creek. Consequently, all these potential artifact bearers must be considered when proposing a date for objects found there.

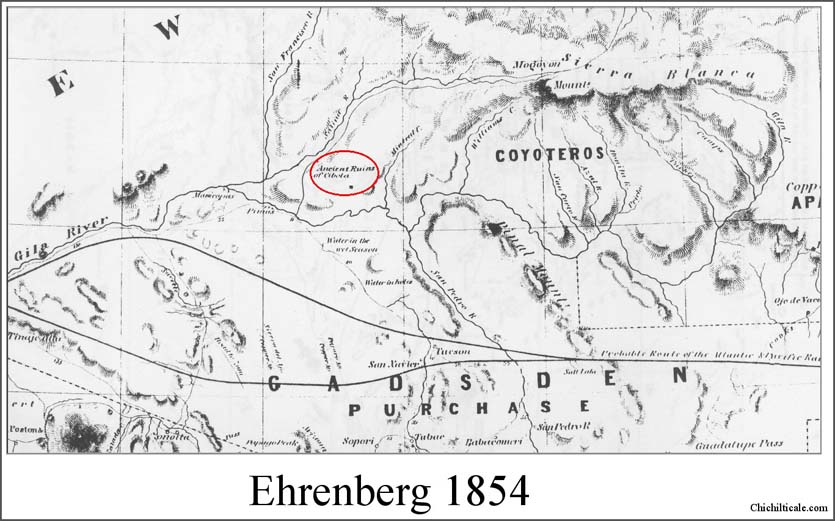

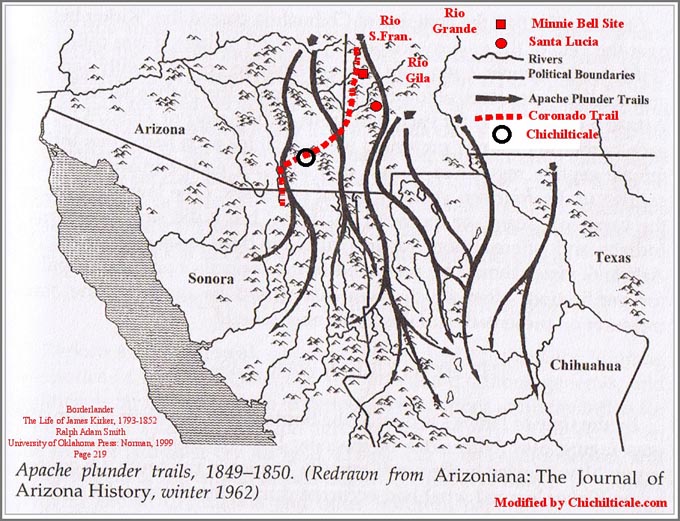

Trade trails pass through and connect settlements. I have previously presented a map of prehistoric communities that I suggest offers the trace of the trade trail followed by Coronado. Even though Coronado reported despoblado, he was almost certainly moving along a trail that had once connected occupied settlements and that was still used by Native American long distance travelers and nomadic bands. In 1539, however, a new herd of travelers appeared along the trail when Franciscan friar Marcos de Niza from Nice, France, at that time controlled by the Italian House of Savoy, and Esteban de Dorantes from Morocco ventured toward Cíbola, subsequently followed by the expeditionaries of Coronado, all these travelers being Europeans and Africans driving domestic animals. Because of the constraint created by the livestock, not all sections of the prehistoric foot trail were suitable, so selection of a specific path was based on accommodation of livestock. For example, while some Native American groups might select a foot trail along a river through a walled chasm, the expedition likely avoided box canyons that offered no escape and where livestock travel was difficult because of rocks and vegetation. The path of least resistance is not the same for foot travelers, horsemen and drovers.(9)

The Coronado Expedition made the first livestock drive from Mexico to Kansas, so the Coronado Trail was the first “cattle trail.” The Coronado drovers were the first contingent of Old World natives to travel this ancient trade road, thereby offering the most likely earliest opportunity for European or African products to appear along the trail. Afterwards, other Old World travelers followed. Paramount to dating metal objects found in the tierra doblada region is convincing determination of whether the artifact under examination resulted from the Coronado Expedition, or was dropped by subsequent Europeans, European-Americans or Native Americans. Written history assists in that determination.

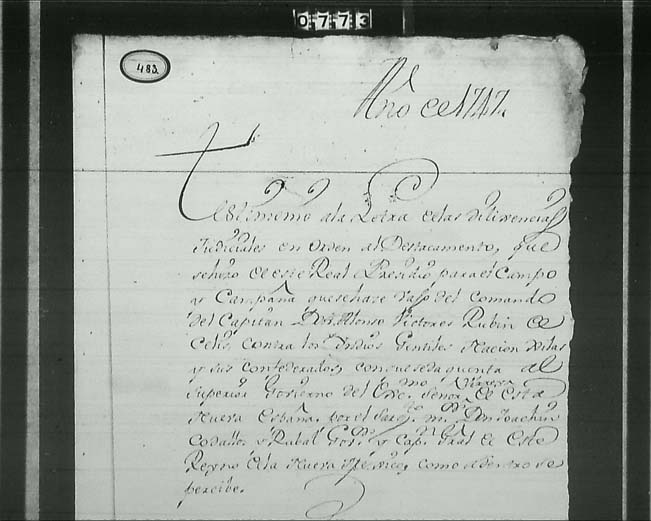

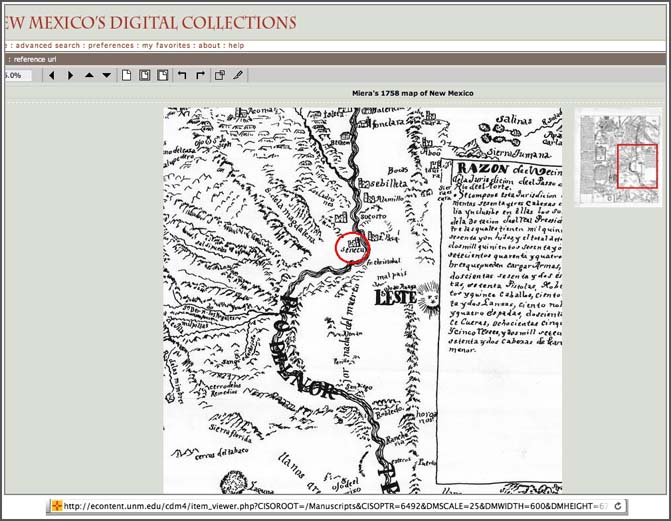

After Coronado departed in 1542, Spaniards next returned to Big Dry Creek in the autumn of 1747 with “The Great Campaign,” as that adventure was tagged. Captain Alonso Victores Rubí de Celís, the presidial commander at El Paso, was commander-in-chief of the seven hundred man force of Spaniards and Indian allies and their herd of over one thousand remount horses. Friar Juan Miguel Menchero served as Chaplain and military adviser – for this the adventure was called by the people “Father Menchero’s Campaign.” Famed cartographer Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco accompanied the expedition and charted the route. Historian John L. Kessell reports that Miera’s original map has not “come to light.” Little detail of the route was offered in an early 1760s report provided by Bishop Pedro Tamarón y Romeral. The Bishop mentioned only that “From the Jornada del Muerto [the expedition] turned west in search of the Gila River. They reached it and made some forays into those vast lands.. They returned toward the north and reached the direct way to and the latitude of New Mexico… .” (10)

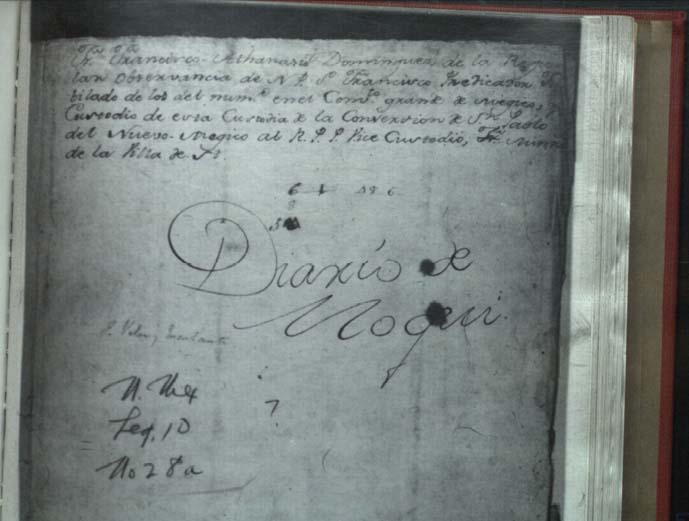

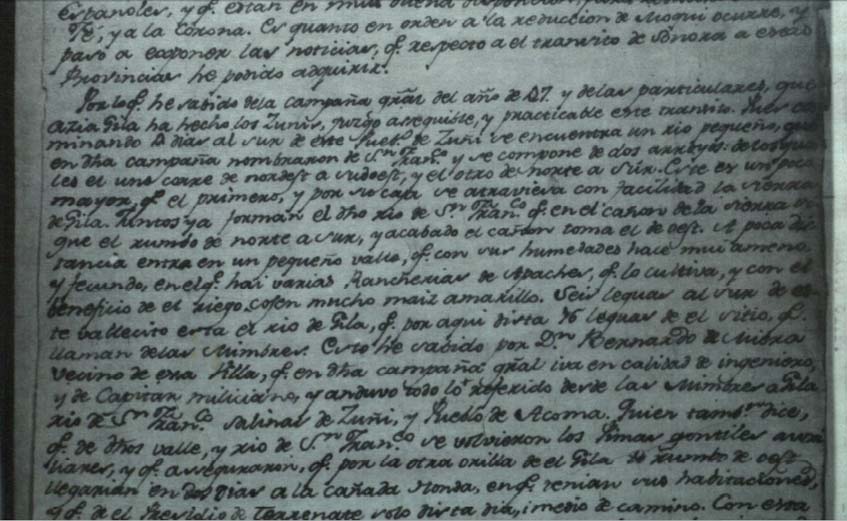

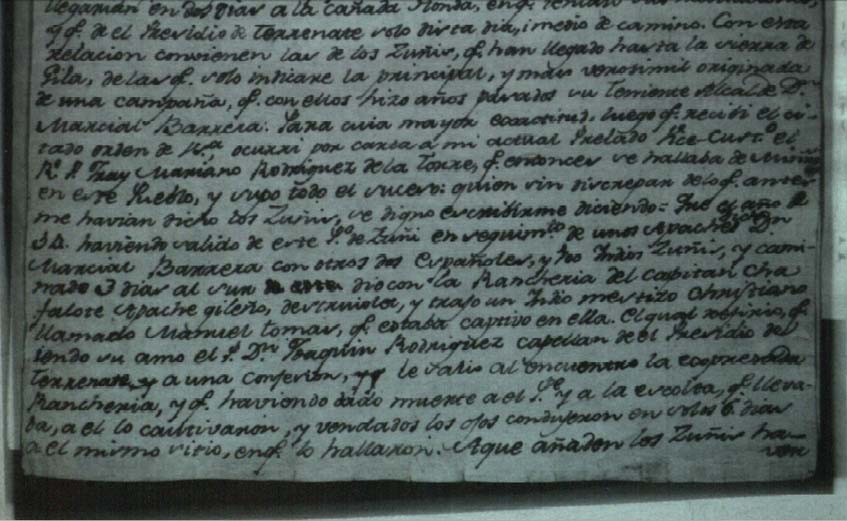

Some thirty years after the campaign, in 1775, Fray Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, in his letter of 28 October 1775 to Gov. Pedro Fermín de Mendinueta, reported what he had learned about the route from Zuni to Sonora. (See Appendix I.) Based on information acquired from Miera y Pacheco and from Zuni Indians, Escalante described the trail:

“… by traveling 4 days towards the south from this pueblo of Zuni, one encounters a small river, which during this (1747) campaign they named the San Francisco. It is formed by two streams, of which the one runs from northeast to southwest and the other from north to south. The latter is slightly larger than the former. By means of [this river's] trough (caja) one traverses the Gila Mountains with ease. Together [these two streams] form the aforesaid San Francisco River, which within the canyon through the mountain range continues a course from north to south. When [the canyon] ends, it takes a course to the west.” (11)

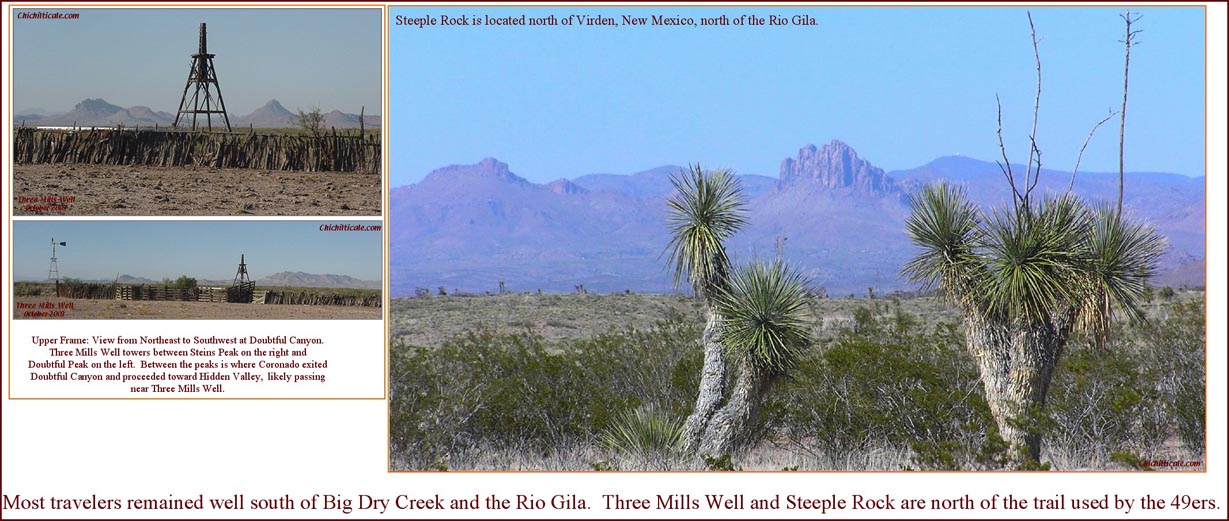

This description fits the drainage and terrain of the combined Río Tularosa and Río San Francisco. Four days by horse south of Zuni, via Hardcastle Gap, are the headwaters of the Río Tularosa, at that spot a small stream flowing northeast to southwest. Just south of Reserve, New Mexico the southwest flowing Río San Francisco joins that stream, claiming the name and continuing to the southwest. Just north of Alma, New Mexico, west flowing Deep Creek and south flowing Pueblo Creek join the Río San Francisco, creating a still larger drainage. The river turns sharply to the south there and flows north to south through narrow box canyons. At Big Dry Creek the Río San Francisco veers sharply to the west, continuing through a box canyon. Given this description, it is more likely than not that the Menchero Campaign was at Big Dry Creek about two hundred and ten years after Coronado had departed. These middle eighteenth-century Spaniards were the first Europeans of currently retrieved written record that could have deposited European products at Big Dry Creek after 1542.(12)

In late November of 1756, a military party numbering over 300 fighting Spaniards and Indian allies camped at Todos Santos, on the Río Gila near modern-day Cliff, New Mexico. The party was composed of the combined forces of Spaniards from Sonora under the command of Captain Gabriel Antonio de Vildósola, and Spaniards from Chihuahua commanded by Captain Bernardo Antonio de Bustamante y Tagle. Father Bartolomé Sáenz represented the Church, and it is his account that has survived for the record. Captains Vildósola and Bustamante sent an exploratory detachment from Todos Santos to the Río San Francisco. Kessell recounts the events surrounding the unit’s mission:

“At this point a detachment set out to the north for the Río de San Francisco to find out if by following its bed or banks one could get through either to the northeast, the direction from which it flows, or to the west, toward which it runs. It was found impassable in either direction because of the narrow gorge between sheer crags of great height along its banks. During this journey from one river (Río Gila) to the other (Río San Francisco), some twenty leagues…”(13)

This description of the landscape fits the box canyons at the intersection of Big Dry Creek and the Río San Francisco, where the south flowing river bends sharply to the west to avoid Outlaw Mountain. I consider it likely that the detachment visited the Slash SI Ranch site. The number of soldiers in the exploratory unit is unknown to me, as is their duration at the site; detachments commonly numbered forty to sixty men. My presumption is a one-night stay by about fifty troops. This military party represented the second Spanish presence at Big Dry Creek since Coronado, and these soldiers could have left artifacts there.

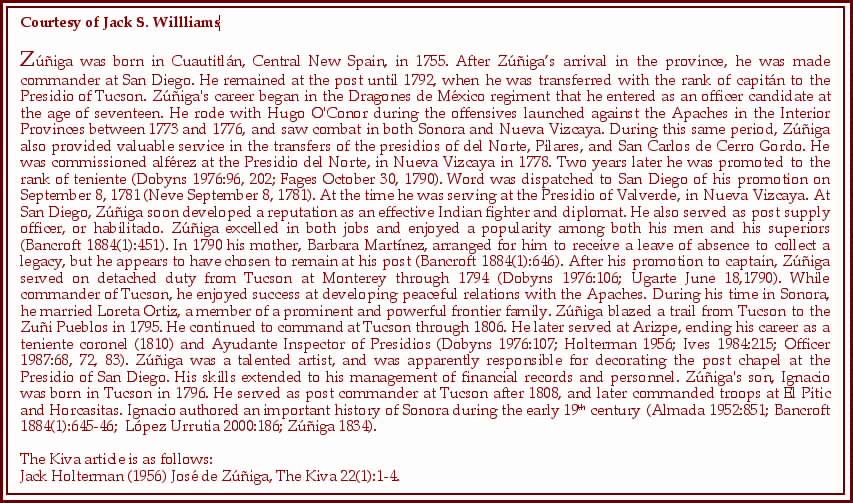

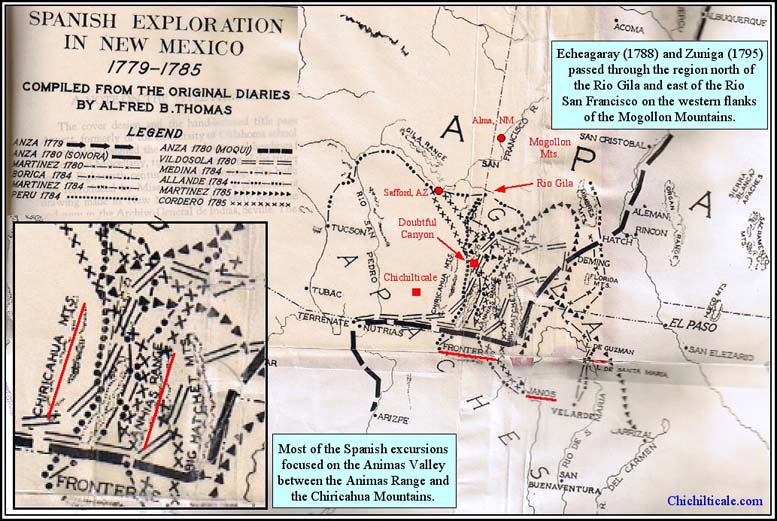

During the last quarter of the eighteenth-century, about two hundred-fifty years after Coronado, two major Spanish military expeditions reached Big Dry Creek. The first of these was commanded by Don Manuel de Echeagaray in 1788, who directed 280 leatherjackets and 120 presidio men, and the second was led by Captain José de Zúñiga in 1795, who directed 151 soldiers and Apaches. Although the cardinal purpose of these campaigns was to find a road from Tucson, Arizona to Zuni, New Mexico, the Spaniards, nevertheless, devoted considerable energy to warfare with the Apaches, attesting to the fact that these Native Americans were present in the tierra doblada. These late eighteenth-century Spaniards could have deposited European products at Big Dry Creek.(14)

The totality of these Spanish, Zuni and Pima routes strongly support my contention that Coronado proceeded along an old and favored trail, one that was followed before him, and continued in use long after he had gone.

The Apaches, of course, remained in tierra doblada after the Spaniards departed in 1795. Beginning in 1815, Apache chieftain Mangas Coloradas used Santa Lucia Springs (modern-day Mangas Springs) as his home, effectively buffering Big Dry Creek from intrusion from the south. Except for the beaver trapping period from about 1825 to 1838, the Apaches enjoyed tierra doblada by themselves. While Mountain Men appeared in the middle 1820s, and although warfare erupted in 1831 when the Apaches and the Mexicans forsake an uneasy peace, beaver trapping in the Río San Francisco region continued. However, in 1837 the mercenary John Johnson befriended and then massacred a group of Apaches in the Animas Mountains, setting off a series of events, including the seizure and warning of trappers, that led to the virtual abandonment of the Santa Rita mines in 1838. The loss of Santa Rita as a trapper supply and storage center, coupled with the economic collapse of trapping caused by depletion of the beaver and the style change from beaver to silk hats, prompted most of the Mountain Men who had not already fled because of the Apache warnings to withdraw that year.(15)

Federal soldiers hunting Apaches likely visited Big Dry Creek in 1856 and 1857. In February 1856, troops commanded by Captain Daniel T. Chandler departed from Fort Craig on the Río Grande south of Socorro for the Río Tularosa near Aragon and Reserve, where they turned south and skirted the western flank of the Mogollon Mountains to arrive at Buckhorn, New Mexico in middle March. There they joined troops arriving from Fort Thorn, also on the Río Grande, that had passed through the Santa Rita copper mines near modern Silver City, thence to Santa Lucía Springs at modern Mangas Springs, thence to modern Cliff, where they crossed the Río Gila and marched to Buckhorn. Because of their likely route, it is almost certain that Capt. Chandler's troops rested or camped at Big Dry Creek. The following year in May, Colonel William Wing Loring led five companies from Albuquerque to the Río Tularosa, thence to a depot at Greenwood Canyon near modern Riverside, New Mexico on the Río Gila. There they joined forces with soldiers from Fort Thorn and Fort Buchanan to launch a campaign against the Apaches that endured into July. This grandiose operation, named the Bonneville Campaign after its commanding officer Colonel Benjamin Louis Eulalie Bonneville, was the first and last of its kind in Apache warfare. Colonel Loring's troops also very likely rested or camped at Big Dry Creek on their southward approach to the Depot at Greenwood Canyon.(16)

Following the American Civil War, settlers and soldiers began to appear in the Río San Francisco valley. Soldiers from Fort Bayard in the south, established in 1866, and Fort Tularosa in the north, built in 1872, began reconnaissance patrols in the valley. Also passing through by the late 1860s were Mormons herding cattle south from Utah to the trailhead at Cliff, thence to Mexico. These drovers built some sojourner cabins at Upper Frisco Plaza near modern-day Reserve. Permanent settlers arrived soon thereafter. Fort Tularosa, located near contemporary Aragon, New Mexico, was abandoned in 1874. That year two ex-soldiers, Patrick H. Kelly and Patrick Higgins, established homesteads on a plaza north of present day Alma, where they raised sheep and sent the wool to Socorro, New Mexico for sale. Also arriving in the Río San Francisco valley that year was Señor Sarraciño. These three were the first permanent non-Native settlers in the Río San Francisco valley south of the Mormon cabins at Upper Frisco Plaza. That same year of 1874, Sergeant James Cooney was sent from Fort Bayard to conduct a mineral survey in the Mogollon Country. As a consequence of favorable signs of valuable metals, Cooney returned to the valley in 1876 and established a mining operation on present-day Mineral Creek, first called Cooney and later Canon City. Miners soon arrived and the camps boomed. In 1878 the permanent and enduring settlements of Alma, Glenwood and Pleasanton were founded.

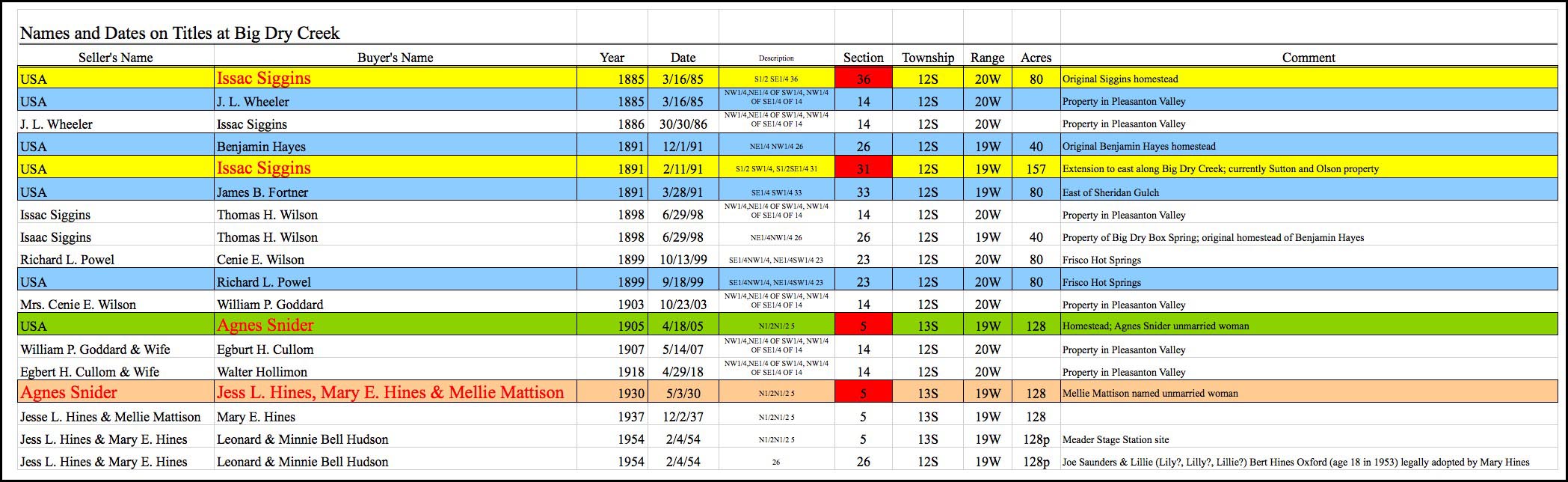

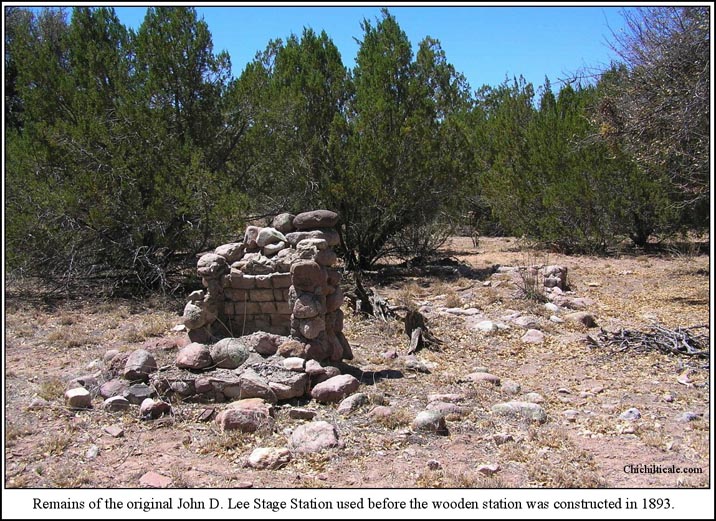

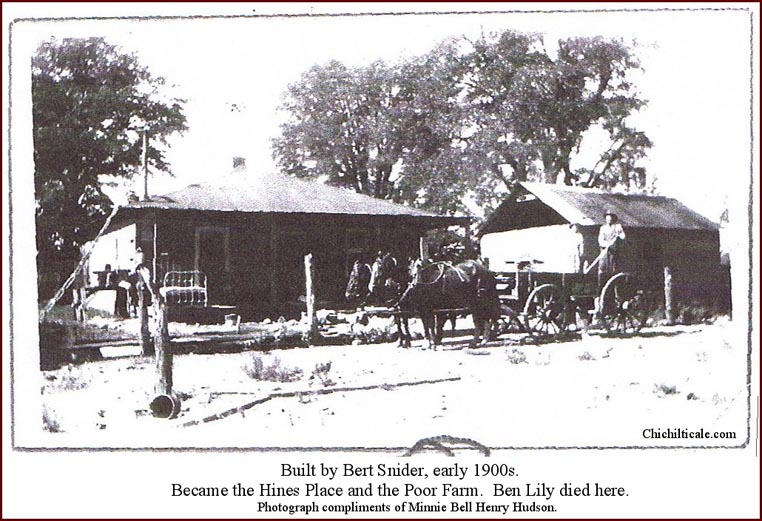

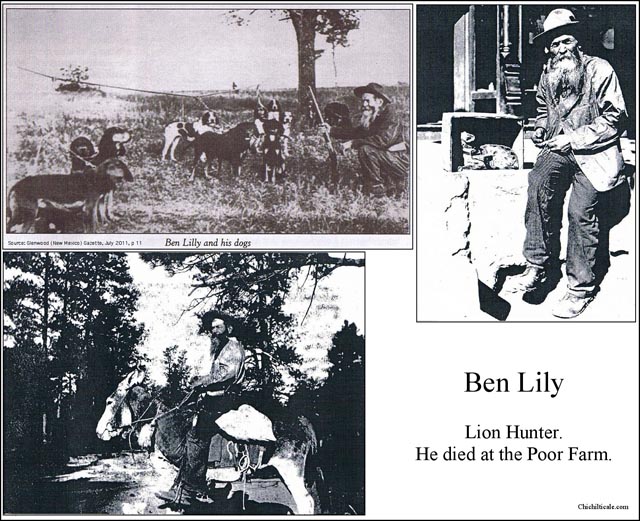

Important for interpreting the ages of artifacts found specifically at Big Dry Creek is to know when American settlers first arrived there. (See Appendix II.) It is likely that Big Dry Creek was a reststop for freight wagons along the road from Silver City to Cooney by 1876, prior to the first buildings on the spot. Traffic increased. Postal service was established in Clairemont, near Cooney, in 1881. The following year a post office was opened in Alma when that settlement was included in the northbound tri-weekly mail run from Silver City. Issac Siggins had founded his ranch on Big Dry Creek before July 1884. By 1885 a constant stage service was in place, the coaches requiring only eight hours riding time between Silver City and Alma. This increasing traffic warranted a station operation on Big Dry Creek. The John D. Lee House & Stage Station appeared before 1889. My exploration model presumes that iron artifacts associated with wagons and homesteaders had appeared at the site of the wagon stop on Big Dry Creek by 1876, and that their numbers increased dramatically thereafter. (17)

As a corollary to this record of historical occupation, cultural evidence of Europeans, Apaches, Mountain Men, scalp hunters, Federal soldiers and American settlers should not be unexpected at Big Dry Creek.(18)

Native Americans on horseback appeared in the very early stages of the colonial period. Historian Richard Flint points out that in late 1539, Don Martín Guavzin or Tlacatecatl, a principal from Tlatelolco and member of the Coronado Expedition, traveled by horse to rendezvous at Compostela. Six days westbound from Mexico City, Don Martín fell from his horse and broke his arm. As a result, he returned home to Tlatelolco, taking many of his subordinate warriors with him. This is one of many examples of the privilege of riding a horse being conferred on converted Native Americans. It was otherwise against the law for indios to ride horses. Of course, this regulation could be enforced only on conquered Native Americans, and, as a consequence, it was not uncommon for gente de guerra or indios bárbaros to obtain and ride horses prior to indios de paz.(19)

Addressing the likilihood of horses from the Coronado expedition providing mounts for Native Americans, Richard Flint wrote that he feels, “… quite confident of (and is in agreement with most other historians about), is that none of the wild horses in the Southwest derive from the Coronado expedition. The horsemen were all mounted on geldings, and there was only one known mare. Quite a number of horses died during the course of the expedition, but we don't know of any live ones that got away. Even it a few did, they were almost certainly all males. Historians are generally agreed that both wild and domestic herds that survive until today in the Southwest descend from stock that came north with Oñate and afterwards or were introduced much later by Anglo-Americans.”

During the 1542 Mixtón War, the Spaniards taught their Native American allies to ride. The inevitable occurred immediately when mounted Native Americans on stolen horses began raiding the Spaniards themselves. The Native Americans initially stole horses and cultivated ramudas, but by 1579 there were large numbers of wild horses and mares in ever enlarging herds, so it was no longer essential to obtain stock by force. The Chichimec War period of 1550 – 1600 caused rapid northward expansion of the mounted Native American. The 1590 expeditionary site of Gaspar Castaño de Sosa discovered near modern-day Carlsbad, New Mexico was a very large corral supposedly used for ganado (cattle, sometimes including sheep), although it could also have corralled horses, or even have been a game trap. During the return of that failed expedition to New Spain in 1591, Native Americans near modern-day Las Cruces, New Mexico attempted to steal horses. These incidents offer evidence that by 1590 Native Americans in New Mexico certainly desired to have horses and may have already possessed them.

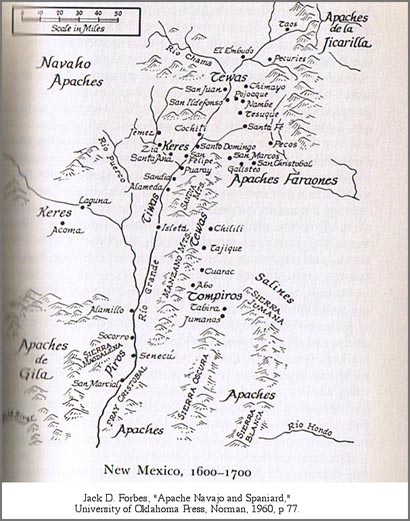

Shortly thereafter these Native Americans achieved their ambition of becoming mounted raiders. If they had not already obtained horses from the south, the arrival of colonist Don Juan de Oñate in New Mexico brought horses to them. Oñate's pioneers of 1598 soon put Native Americans to work as shepherds, and some of these livestock stewards fled and took animals with them, thereby providing horses to Native Americans soon after the coming of the Spaniards. Within eight years of Oñate's arrival in New Mexico, raids by mounted Native Americans were first recorded. Historian Donald E. Worcester provides documents and interpretation showing that "Apaches began acquiring horses as soon as there were any to be had" and that "Oñate's first settlement was soon the target" of Apache raids. Livestock theft in Río Arriba was a serious problem by 1608. That year Father Lázaro Ximénez complained to the viceroy that Apaches were stealing the Spaniards' horses. Historian Jack D. Forbes writes that between the years 1610-1621, "…all of the Athabascans ("Apaches") in the New Mexico area must have acquired horses.”(20)

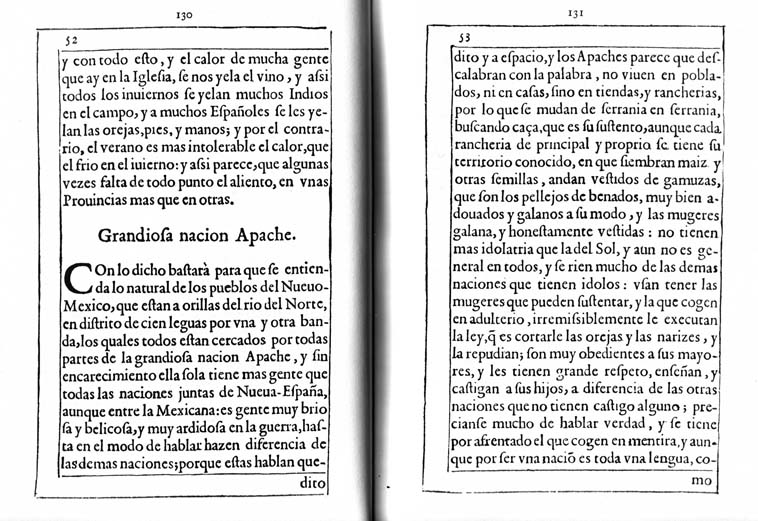

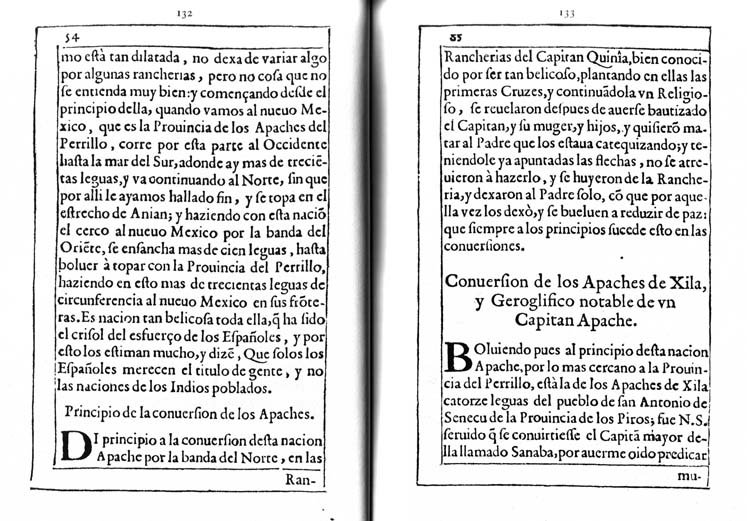

After the arrival of Oñate, conflict between Spaniards and Apaches intensified, as did Apache raiding. By the 1620s, and probably earlier still, the Spaniards were aware of Apaches in the Gila region. Father Alonso de Benavides described the Indians of the regions of New Mexico, and he distinguished between the Xila (Gila) Apaches and the Perrillo (Mescalero) Apaches by claiming that the Gila Apaches lived west of the Río Grande. Benavides described the territory of the western group of the “Grand Nation of the Apaches” as:

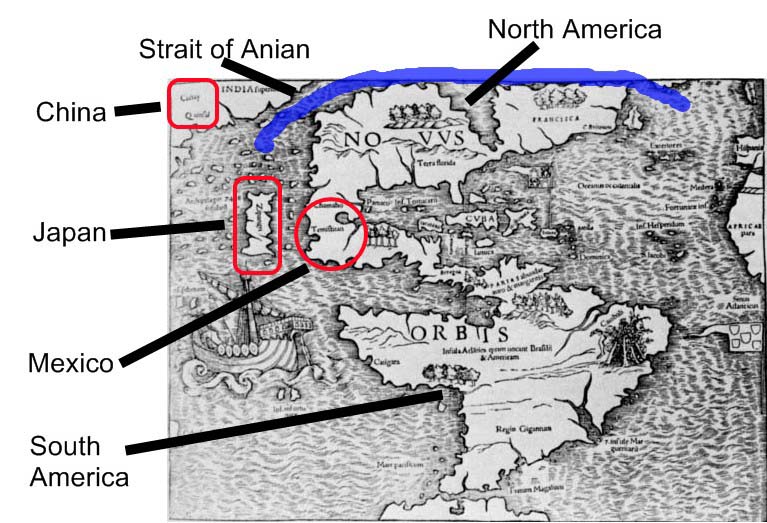

“When we go to New Mexico, starting from the beginning of it [the Apache nation], which is the province of the Perrillo Apaches, it [the nation] runs through that area toward the west as far as the Mar del Sur (Pacific Ocean), in which there is more than three hundred leagues. And it [the nation] continues toward the north without our having found its end there. And it [the nation] runs into the Strait of Anian (Bering Strait).”

Specific to the Gila Apaches, Benavides writes that the Apaches nearest the Perrillo were “the Apaches de Xila, fourteen leagues from the pueblo of San Antonio de Senecú de la Provencia de los Piros.” Senecú is considered to be near San Antonio, New Mexico, south of Socorro. If so, this description, depending upon the distance used to define a league, and upon which direction is chosen, locates Xila Apaches in the 1620s some forty to seventy miles west of Senecú. This expanse includes the mountains of southwestern Socorro county, easternmost Catron county, and the Plains of San Augustine, all part of Apachería.(21)

My exploration model includes the presumption that upon the arrival of mounted Europeans to the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts and to Río Arriba, Apaches targeted this new group for rustling and enjoyed instant success. Immediately mounted raiding commenced using stolen technology – the horse. Raiding increased through time. It follows that plunder would appear immediately in Apachería. As the Spaniards moved northward from central Mexico, the quantity and types of European products increased in the Apache region. This influx of exotic material to Apachería complicates assignment of European artifacts solely to European bearers – Apaches could have brought an object to where it was recently found.(22)

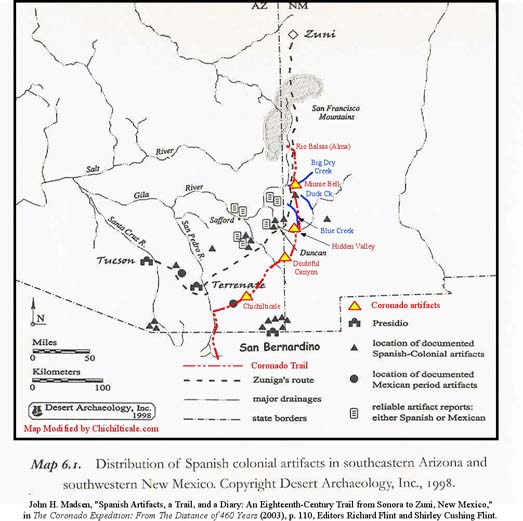

Evidence of Apache raiding of Europeans can be demonstrated by assigning an artifact to one of two populations. One artifact population is associated with locations of reported or interpreted Spanish presence. The contrasting population is composed of pieces that are associated with little or no reported Spanish presence. Archaeological researcher John H. Madsen presented a map in 2003 showing the locations of reported Spanish artifacts. I generated a map of reported Spanish presence. One of the measures I used to define Spanish presence was the cartography of historian Alfred B. Thomas, who published a map of Spanish military excursions in southwestern New Mexico and southeastern Arizona from 1779 to 1785. The map shows the concentration of these patrols to be in the Bootheel region of New Mexico and the San Bernardino – San Simon valleys of Arizona. I observed that of twenty-one Spanish artifacts shown by Madsen, all but two came from areas of reported Spanish presence. Attesting to this strong Spanish presence mapped by Thomas are Spanish artifacts contained in private collections that were recovered from the Peloncillo Mountains. Some of these pieces were shown to the organizers of the "Coronado Road Shows" in 2004 .(23)

There are additional artifacts to consider. I have examined private collections and can report that Spanish colonial artifacts from the Blue Creek region north of the Río Gila in southwestern New Mexico include spurs, stirrups, bits, buckles and copper utensils. Most of these pieces, but not all, were found in extremely remote locations off main trails, suggesting an Apache bearer rather than a Spaniard. The Blue Creek region almost certainly lies outside Spanish presence between 1542 and, perhaps 1747 or 1784, maybe even 1788 – Thomas' map shows only one 1779 to 1785 patrol, a 1784 excursion, reaching as far north as the Río Gila in New Mexico. I have pointed out that the Spaniards in Sonora did not return to the region north of the Río Gila after Coronado until brief excursions in 1747, 1756, 1788 and 1795. Thomas does not include these four expeditions on his map. Madsen's map shows two Spanish artifacts outside the region of intense Spanish presence. I interpret his map to show that one of these is located approximately fifteen miles east of Cliff, New Mexico. The other is shown about ten miles southeast of the conflux of Big Dry Creek with the Río San Francisco; since I interpret that the 1747, 1756, 1788 and 1795 expeditions visited Big Dry Creek, this particular artifact might be from one of those excursions. Or it might have been brought there by an Apache.(24)

One specific Blue Creek region buckle merits special mention. This piece was found on the north side of the Río Gila a short distance from Hidden Valley, the site I have proposed as Coronado’s advance party camp of 24 June 1540, as well as a camp for the following and retreating armies. About the artifact, John Powell, a St. Augustine, Florida curator, conservator, and authority on Spanish buckles, wrote:

“This is very definitely a 16th century buckle. Its sheer weight and robust construction would tend to suggest that it is more likely an upper class harness or saddlery buckle than something worn on a sword belt or other accoutrement. The other thing that raises an eyebrow is the fact that the tine/tongue was attached to the outer edge of the buckle frame rather than to the center bar. Later Spanish accoutrement buckles were also made this way, and I’m not exactly sure how they worked. But the period during which this was made and used very nicely corresponds to that during which the Coronado/Soto expeditions took place. I have seen quite a few pieces of brass or bronze found out West with the same very dark patina this buckle exhibits. It’s very nice and very unusual.”

This buckle strengthens our exploration model by providing confidently identified sixteenth-century material evidence near Hidden Valley, a location predicted by the model to be a Coronado campsite. With this find, there is now material evidence of the Coronado Expedition at Kuykendall Ruins, Doubtful Canyon, Hidden Valley, and Big Dry Creek. My exploration model predicted all these to be Coronado camps along an ancient trail.(25)

The exploration model presumes that Spanish artifacts found in Apachería could have arrived there from New Spain to the south or from New Mexico to the east, and that their arrival from a southern source following the Coronado Expedition could have been as early as the final decades of the 1500s. Consequently, the team always considers the Apache complication when assigning pieces to a specific bearer, especially artifacts proposed to be late sixteenth-century and early seventeenth-century.

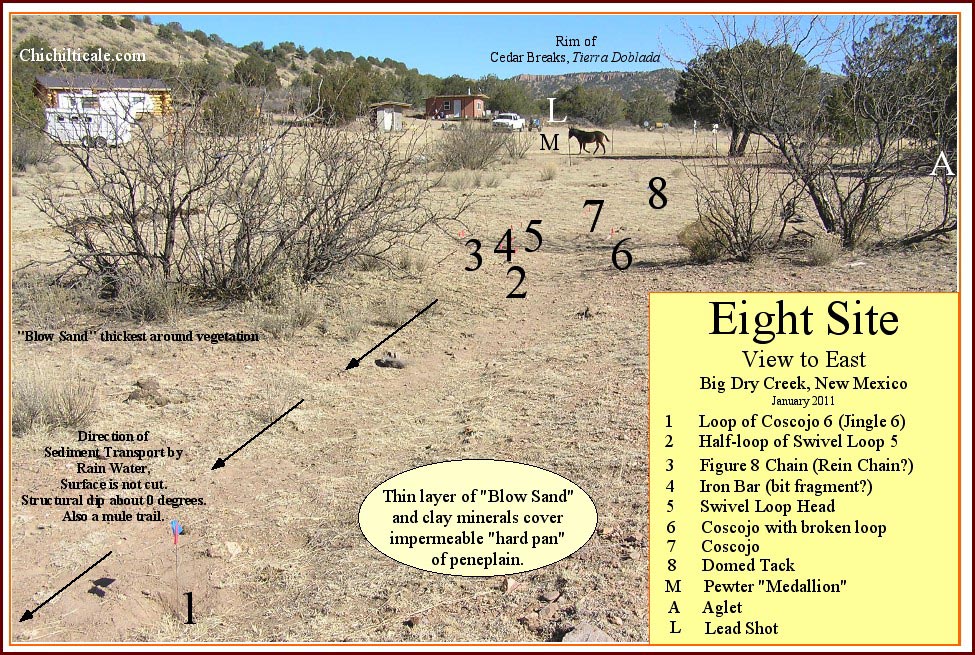

Initial metal detecting on the Minnie Bell site focused on two properties – the Kenny and Debra Luera Sutton and Marianne Sutton tract, and the Dave and Donna Olson tract – both located on the northern side of Big Dry Creek on a topographic bench overlooking the watercourse. Our exploration began 23 October 2010 on Sutton property located above the north cutbank of Big Dry Creek. Employing a Blennert sled and handheld metal detectors, the team of Minnie Bell, Loro Lorentzen and I systematically explored the Slash SI Prospect. By the spring of 2011 we had searched the available accessible portions of the Sutton and Olson tracts. We found evidence of prehistoric Native Americans, of the sixteenth-century Coronado Expedition, and of at least one of the eighteenth-century Spanish expeditions of Menchero, Vildósola–Bustamante, Echeagaray and Zúñiga. Also we found possible evidence of Mountain Men, fur trappers and scalp hunters of the 1820s to 1840s, evidence of nineteenth-century Apaches, of Federal military personnel of the last half of the nineteenth-century, and of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century homesteaders.

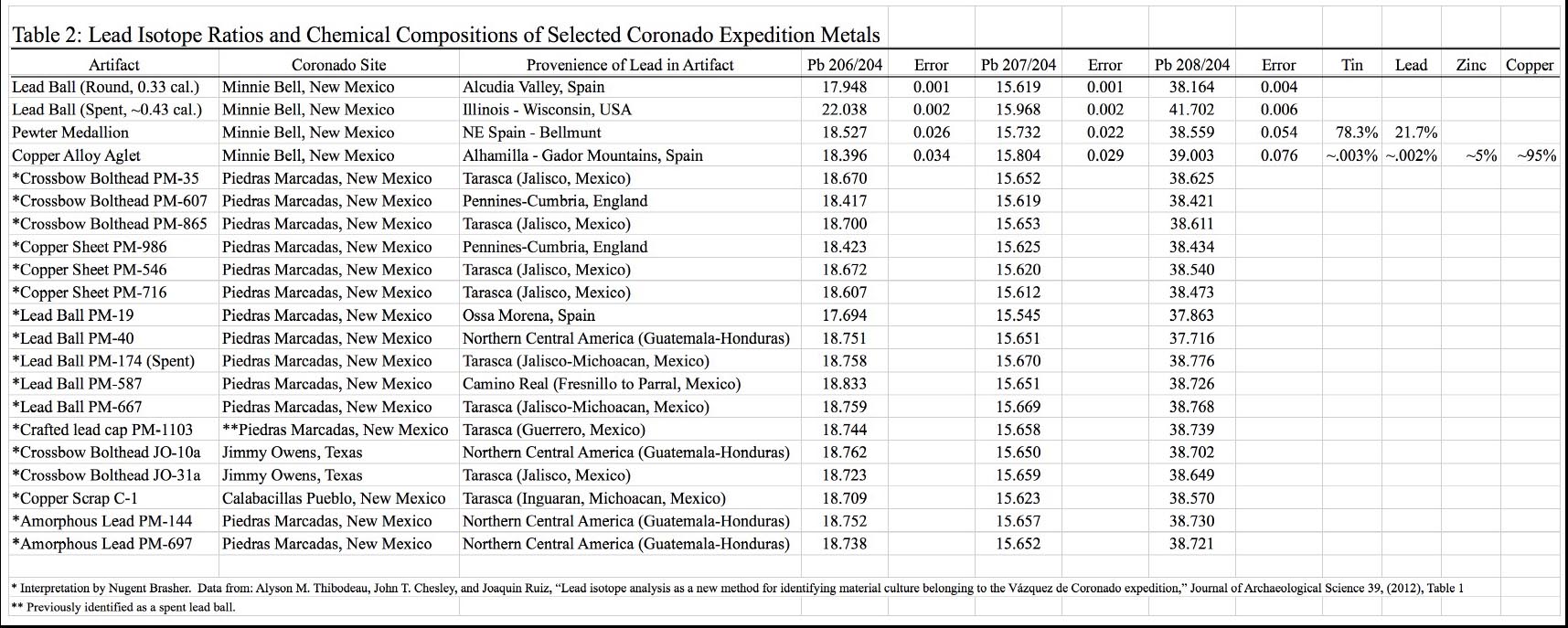

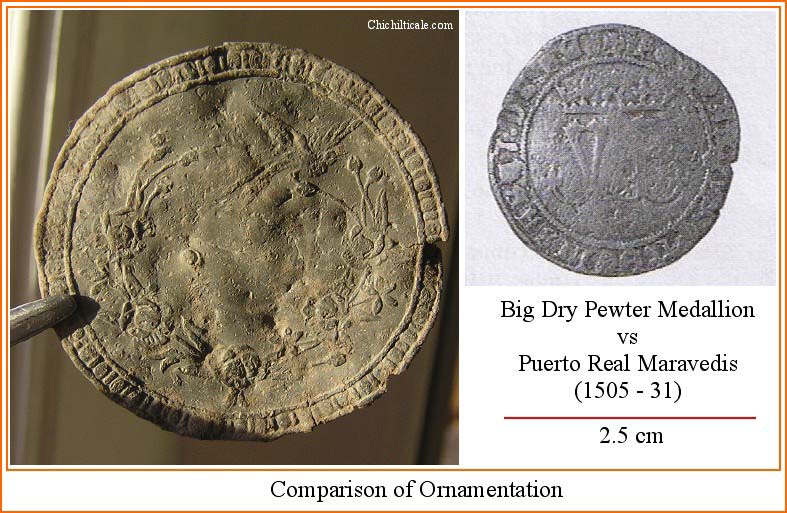

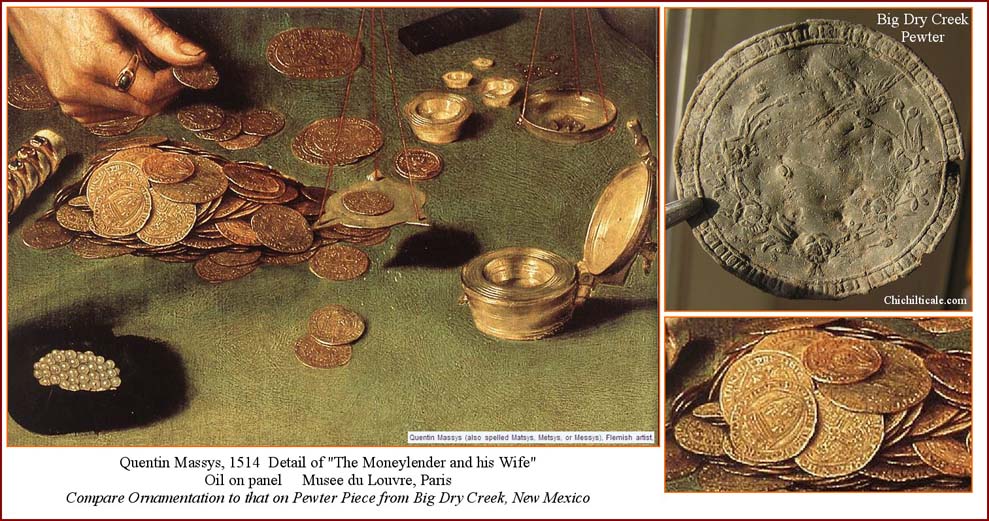

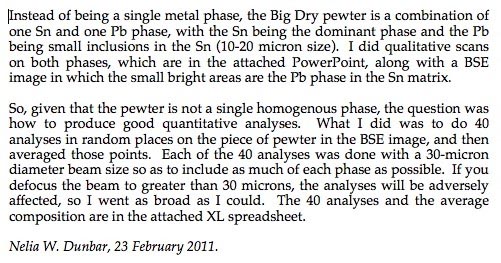

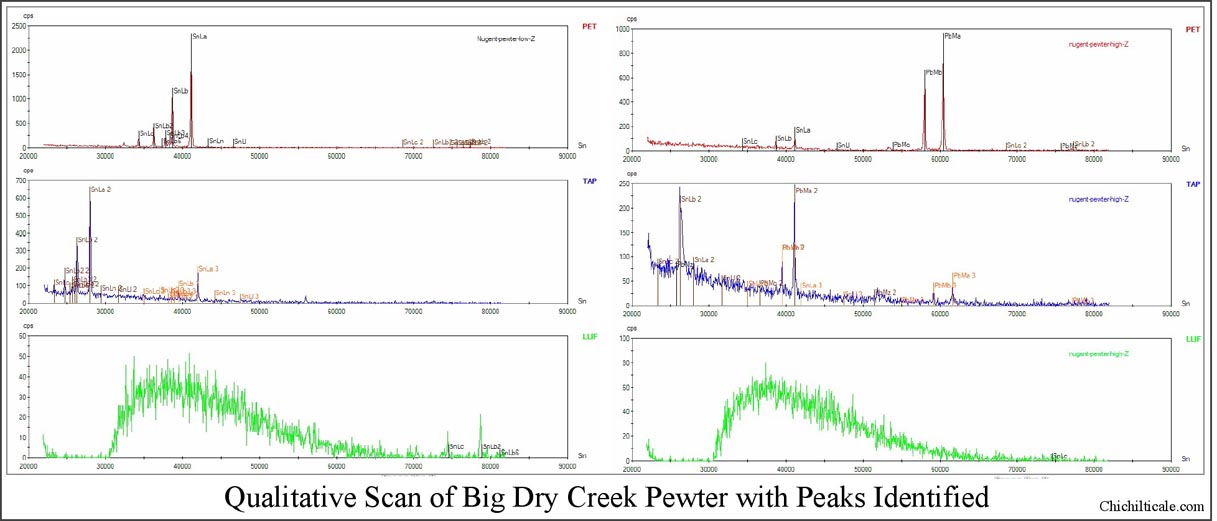

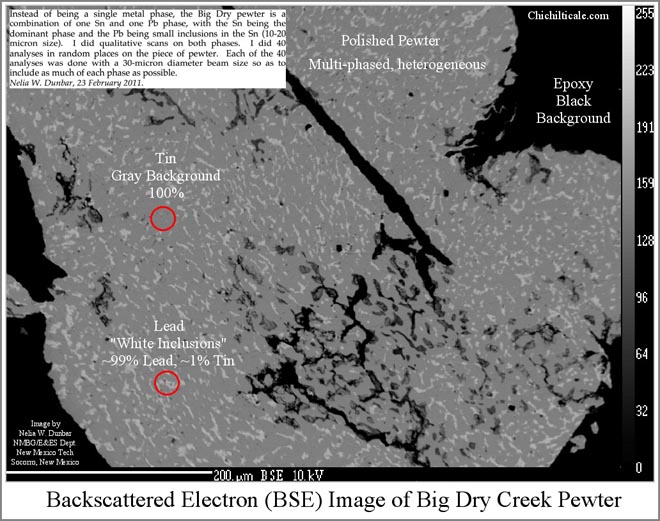

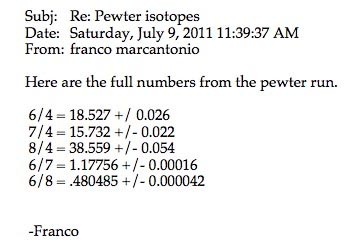

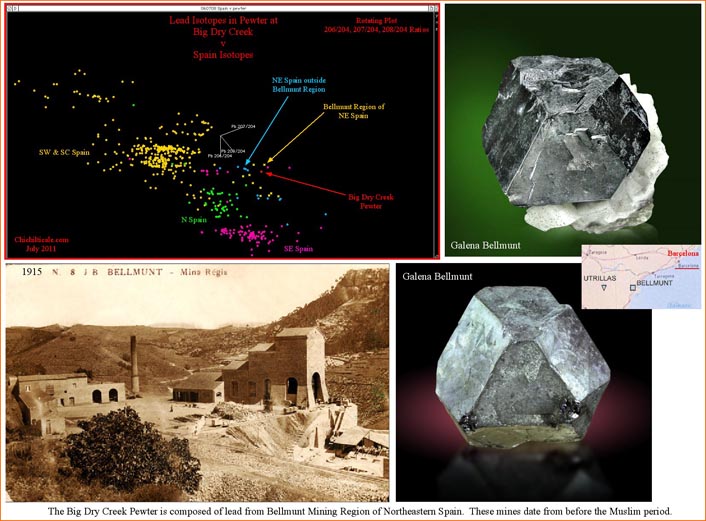

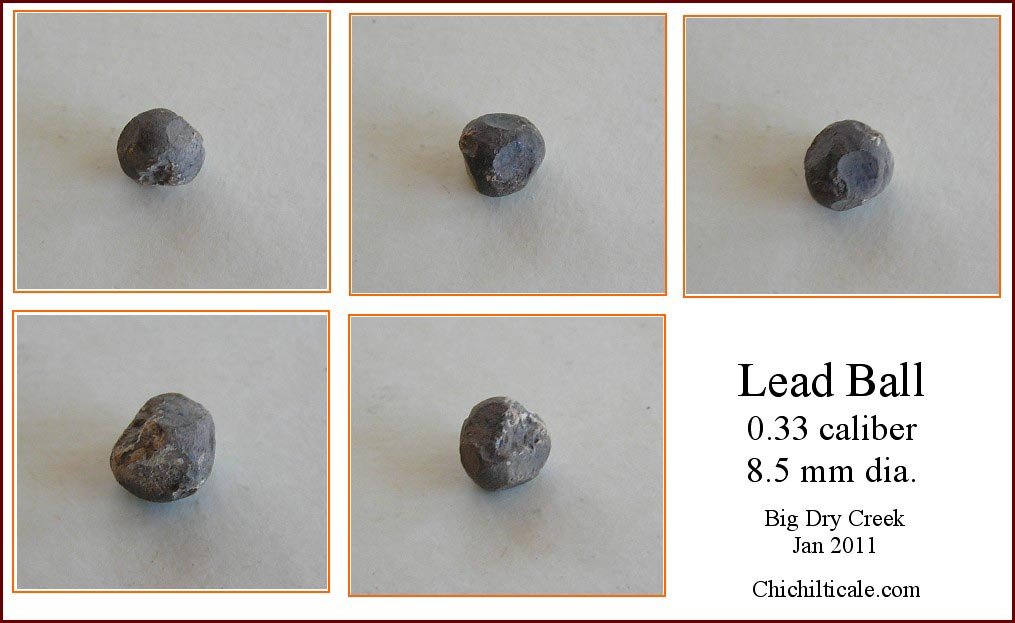

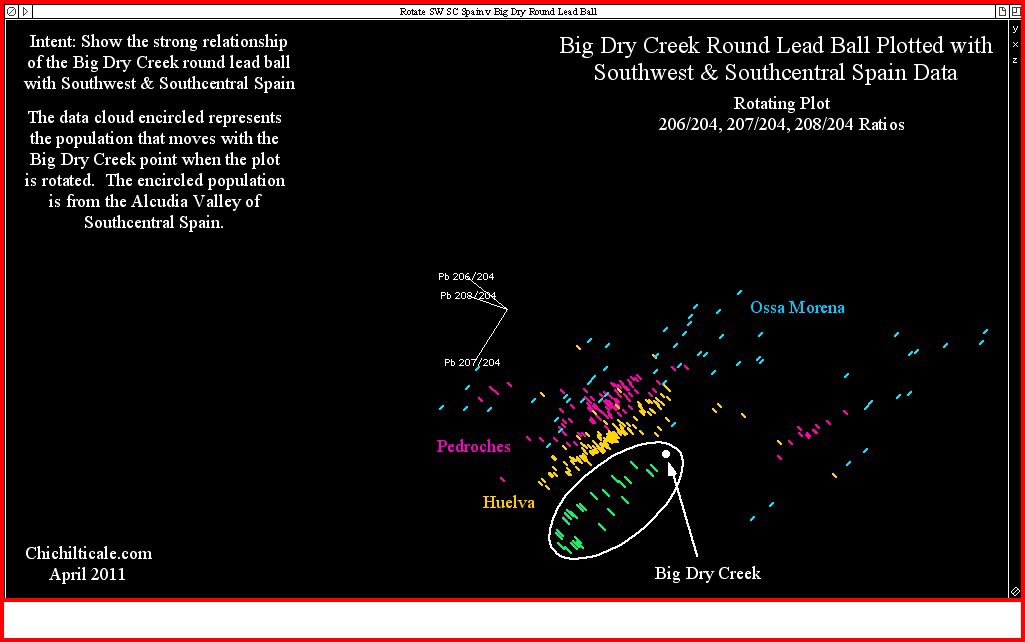

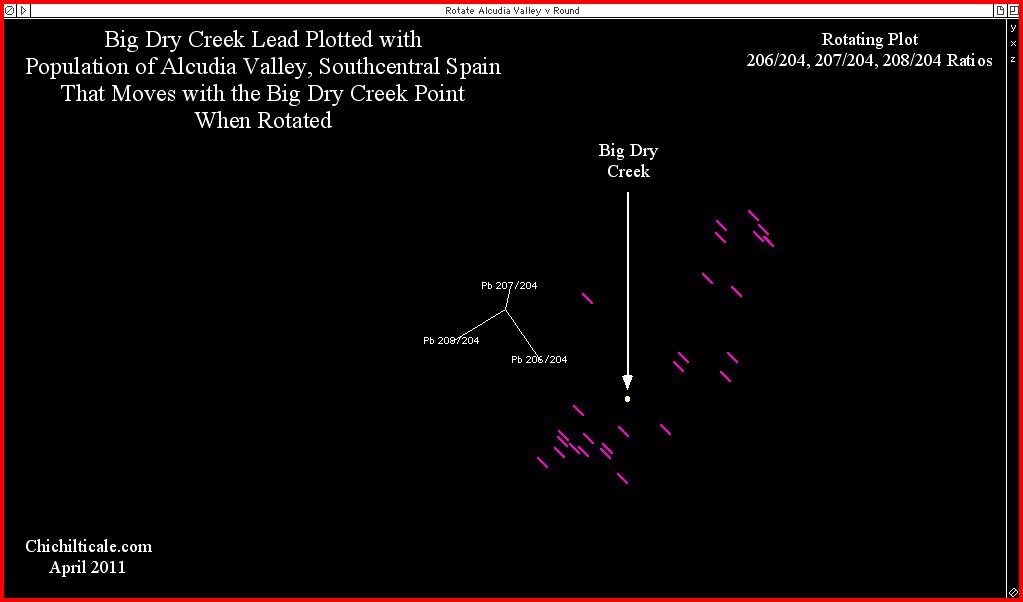

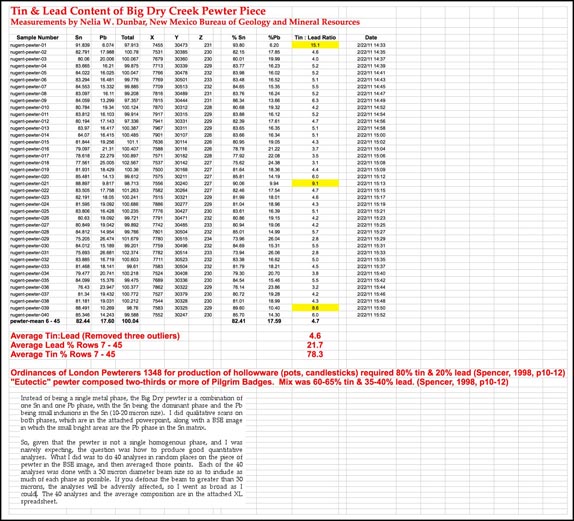

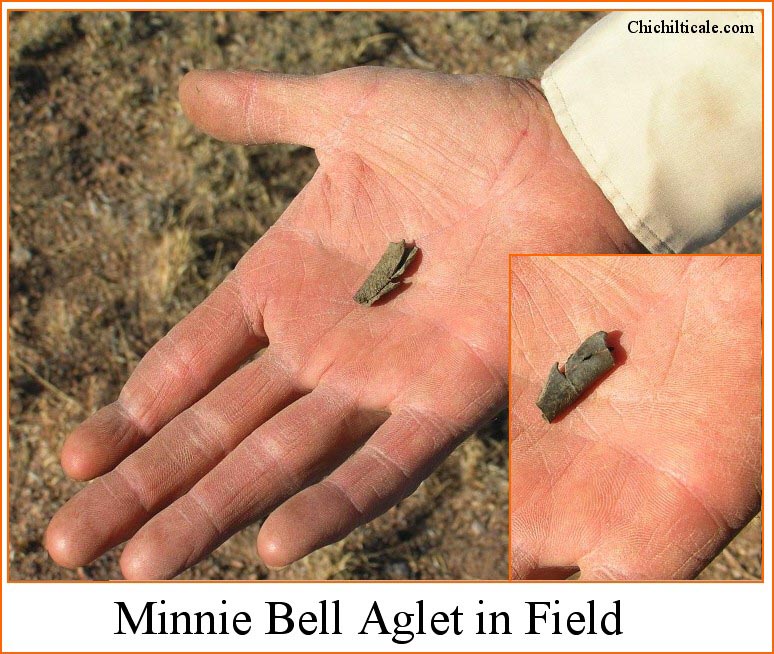

On the eastern end of the topographic bench above the northern cutbank on the Olson property the team found a pewter medallion, two lead balls, one round and one flattened, and a copper-alloy aglet. We employed electron microprobe analysis to determine that the chemical composition of the pewter medallion was 78.3% tin and 21.7% lead with no other measurable elements present. We used Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry (TIMS) to measure the lead isotope ratios of the lead present. Our subsequent analysis determined the source of the pewter lead was the Bellmunt region of northeastern Spain, mined since before the Muslim period. We likewise used TIMS to measure the isotope ratios of the round lead ball found 225 feet east of the pewter medallion. Based on our analysis, we confidently concluded that the source of the lead in the round ball was the Alcudia Valley of south-central Spain. Previously I have written that lead from Spain found within the Coronado travel corridor extending from Palominas, Arizona on the south to near Hawikku, New Mexico on the north is almost certainly a product of the Coronado Expedition. We consider the pewter medallion and the round lead ball to be powerful evidence supporting the presence of Capt. Gen. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado at Big Dry Creek, New Mexico.(26)

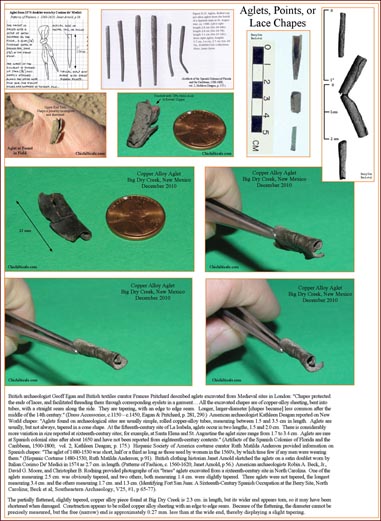

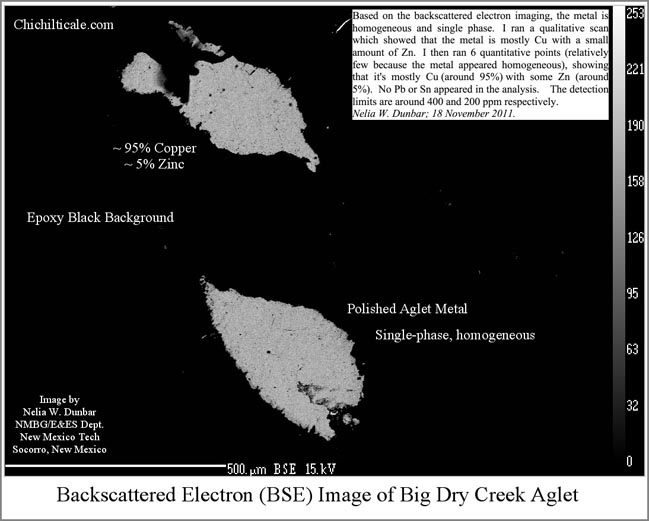

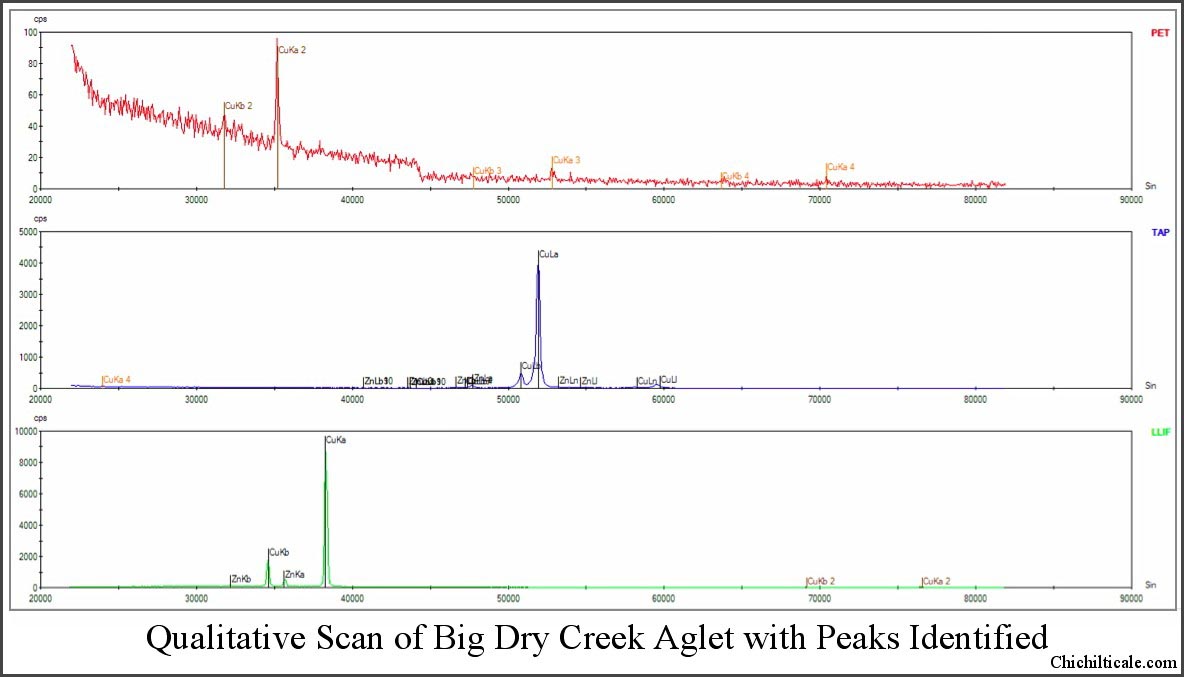

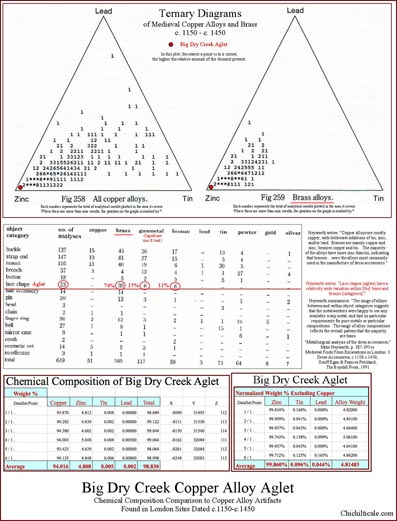

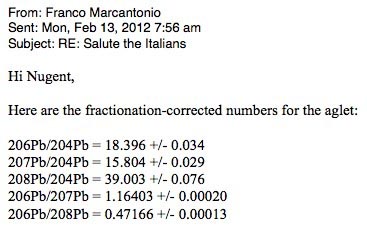

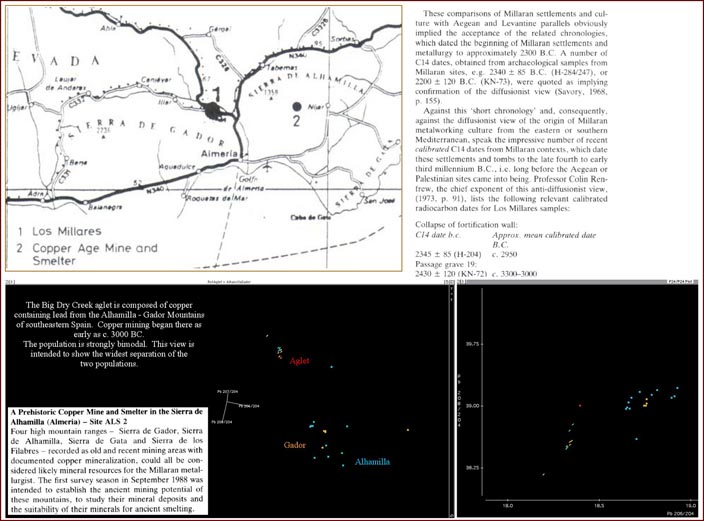

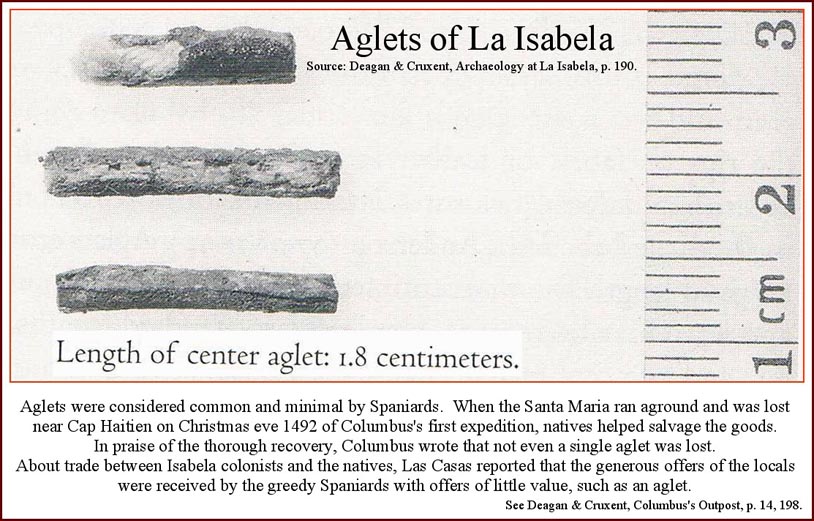

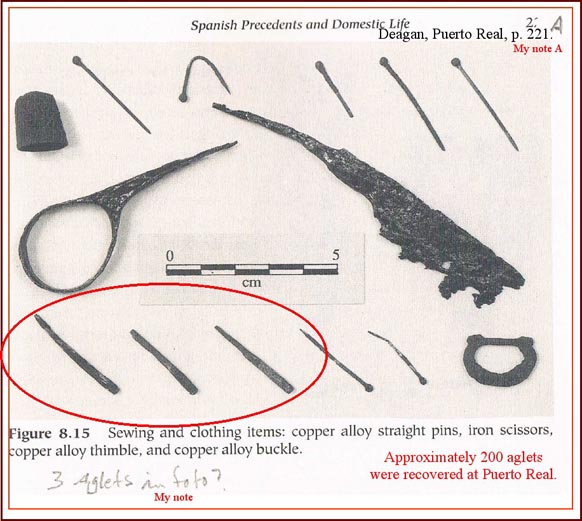

The copper alloy aglet found 135 feet southwest of the pewter medallion was discovered under a juniper tree that forced swing-stick metal detecting by Loro Lorentzen. As with the pewter medallion, we employed electron microprobe analysis to quantify the chemical composition of the alloy. The results showed ~ 95% copper and ~ 5% zinc, thereby defining the metal as “brass.” Metallurgical analysis of English lace chapes from c.1150-c.1450 demonstrated that of 53 measured, 39 were brass, 6 were bronze, and 8 were gunmetal. The Minnie Bell site aglet contained enough trace element lead for measurements of the lead isotope ratios by TIMS. We concluded the lead to be from the Alhamilla - Gador Mountains of southeastern Spain, mined for copper as early as c. 3000 BC, perhaps the oldest copper mining region of the Iberian Peninsula.(27)

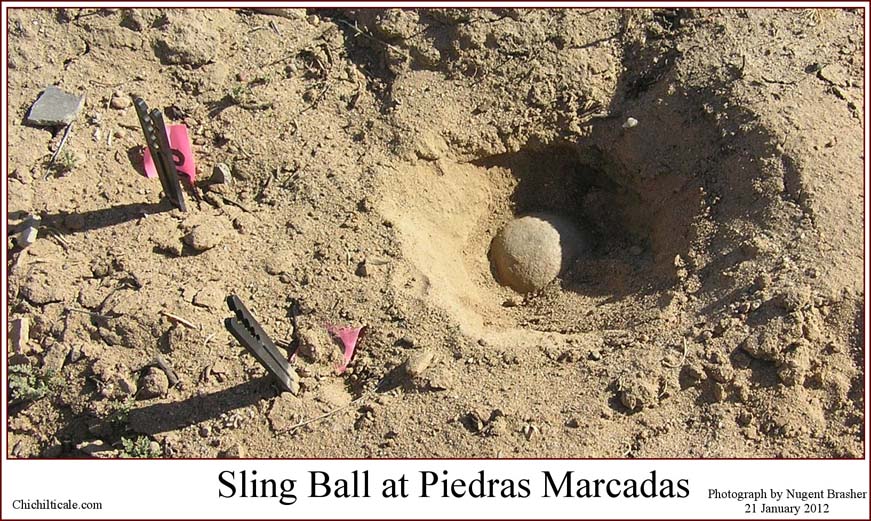

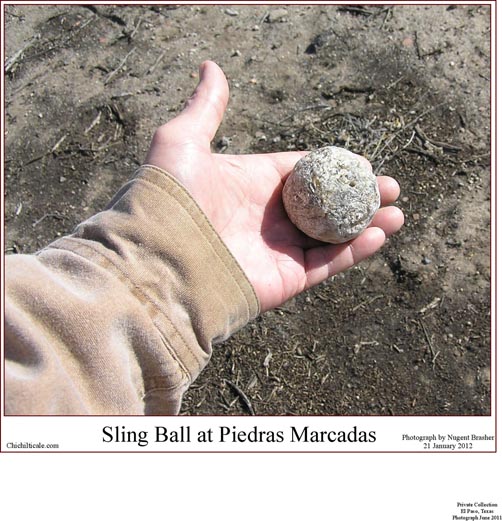

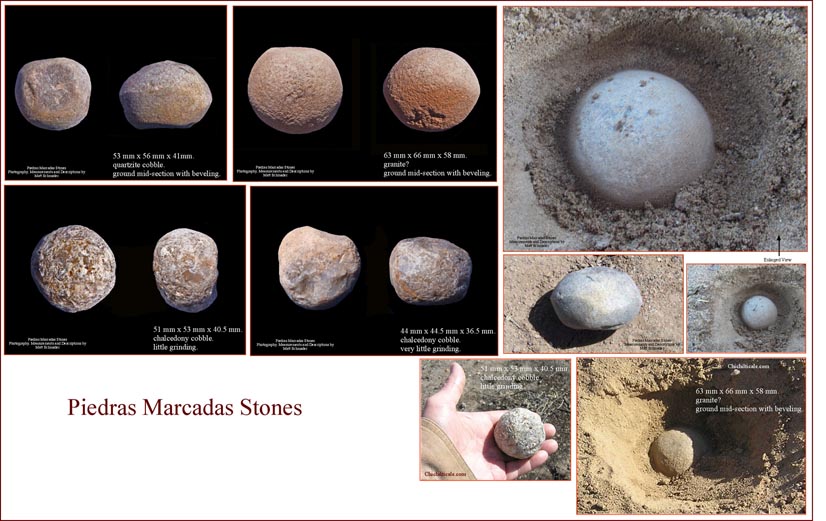

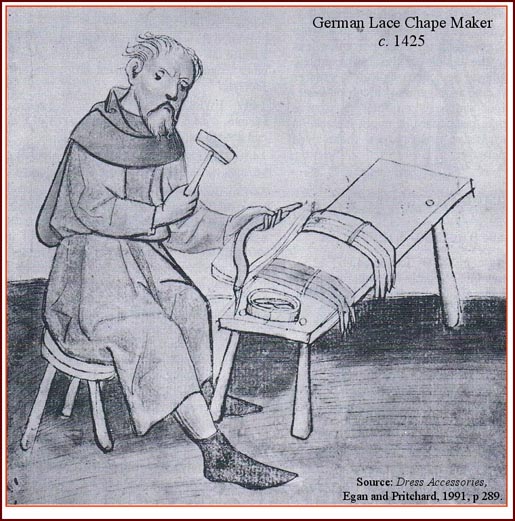

Aglets are also known as points, or lace chapes. Richard Flint described aglets: "At [Coronado] time, many components of dress were laced together, as, for instance, sleeves and a jerkin or hose and a doublet. The many laces employed were each tipped with metal cones (aglets).” Aglets have been reported at two Southwestern Coronado sites and at two isolated sites near Aztec, New Mexico. Since the 1990s, one copper and two silver aglets were recovered at the Jimmy Owens Site, and fifteen copper aglets were found at Piedras Marcadas. Aglets are temporally restricted. Archaeologist Kathleen Deagan reported, “Aglets are rare at Spanish colonial sites after about 1650 and have not been reported from eighteenth-century contexts." Hispanic Society of America costume curator Ruth Matilda Anderson believed that by the 1560s “few if any [Spanish] men were wearing" aglets. Richard Flint wrote, “Cunnington and Cunnington indicated that in Britain aglets were 'very fashionable from 1510-1640s.” If our identification is correct, and because aglets are not reported at Spanish sites after the end of the 1600s, and because there is no indication of Spanish presence in tierra doblada from 1542 until 1747, and because the lead in the aglet is of Spanish origin, then the aglet, more likely than not, reached Big Dry Creek with the Coronado travelers. We consider the aglet to be equal in importance to the round ball and the pewter medallion, all three composed of Spanish lead, as an indicator of the presence of the Coronado Expedition at the Minnie Bell site.(28)

In addition to lead isotope ratios from metallic artifacts found at the Minnie Bell site, Table 2 includes lead isotope ratios of lead objects and of trace element lead in copper objects from Piedras Marcadas and Calabacillas Pueblo, New Mexico, and the Jimmy Owens site in Texas. Previously, I have presented isotope data from Kuykendall Ruins, Doubtful Canyon, Hawikku, Piedras Marcadas, and Jimmy Owens. Our analysis of this dataset finds that source locations contributing lead shot are Spain, Central America, and Tarasca (western central Mexico). Locations contributing copper alloy, lead and pewter artifacts include Spain, Central America, Tarasca, and England. The proveniences of the various lead from these sites display a wide geographical expanse of source locations of metals utilized by the Coronado Expedition. This diversification suggests that expeditionaries carried metal from Europe, and that they also utilized the copper and lead found in Tarascan and Central American mines.(29)

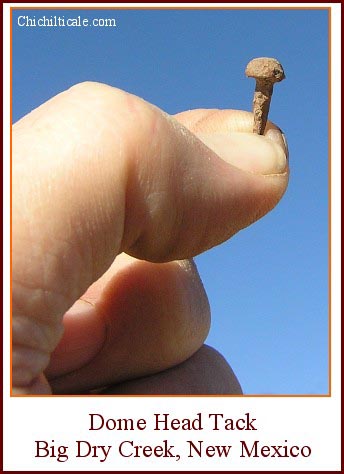

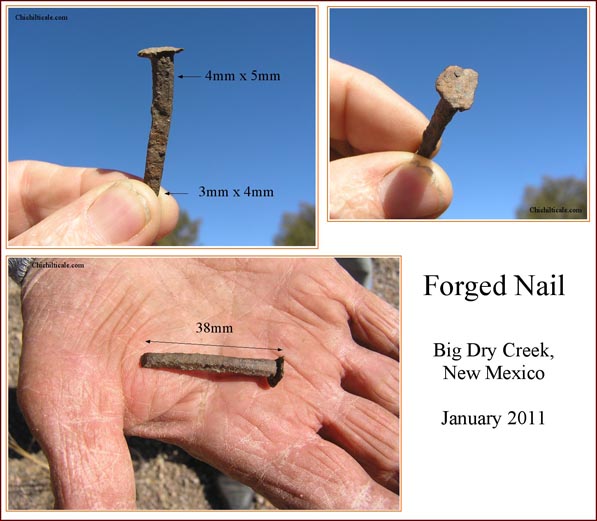

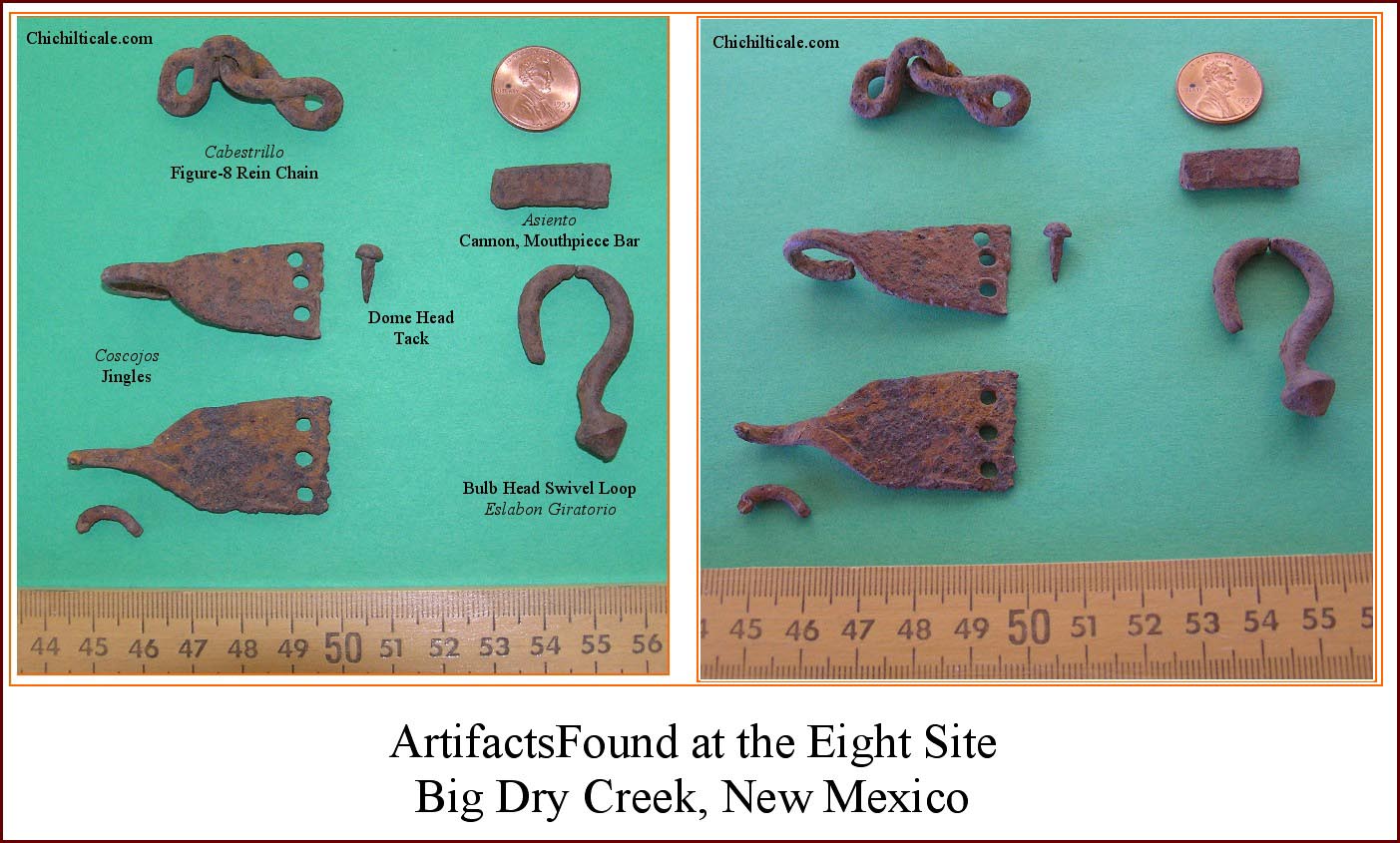

On the northeast cutbank thirty feet from the aglet, at the head of a subtle, almost imperceptible, rainwater drainage most obvious as a reptile trail, we found a forged, wrought dome-head tack. These tacks were available in the sixteenth-century, so the piece could be a product of the Coronado Expedition. Although such tacks persisted into the nineteenth-century, a date of arrival for this particular tack at Big Dry Creek subsequent to the sixteenth-century is not likely. The 1700s Spanish soldiers were probably less inclined to carry tacks than had been the domestic Coronado expeditionaries who preceded them by some 200 years. Mountain Men or scalp hunters from the first half of the 1800s were also unlikely to carry these tacks. Apaches were not likely to collect tacks on their raids. By the middle 1800s, wrought nails had become uncommon in America. At the time the first homesteaders and Federal soldiers arrived at Big Dry Creek, nails cut by machine from sheet metal dominated the American market and did so until the late 1880s when round wire nails began to account for almost all nail production. We concluded that the dome-head tack is more likely than not a residual of the Coronado Expedition.(30)

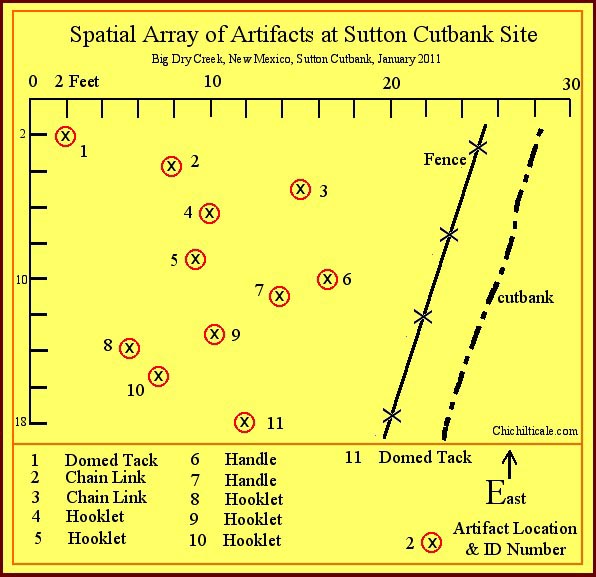

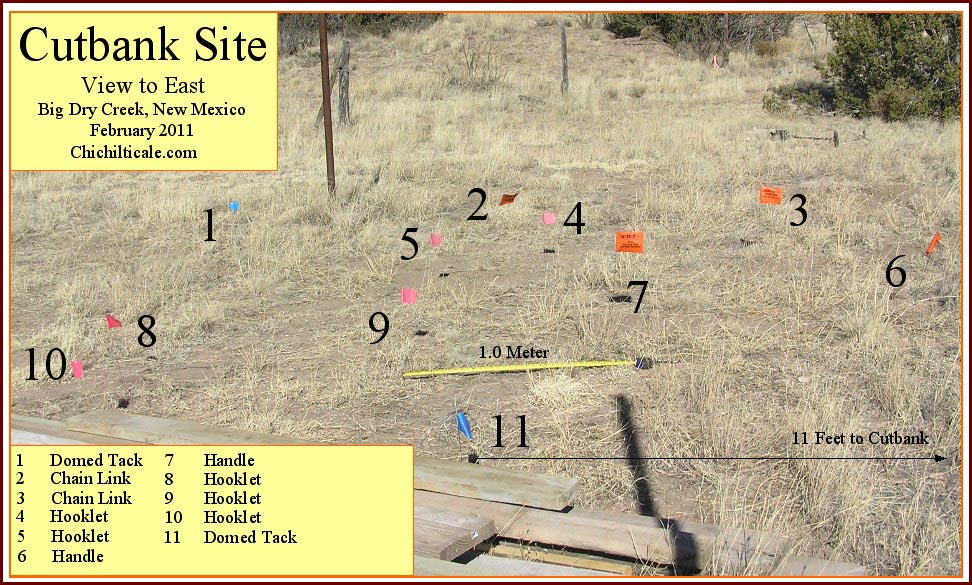

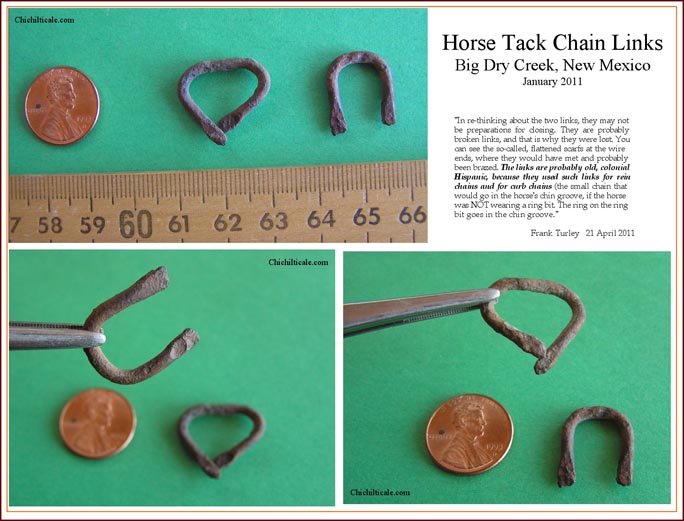

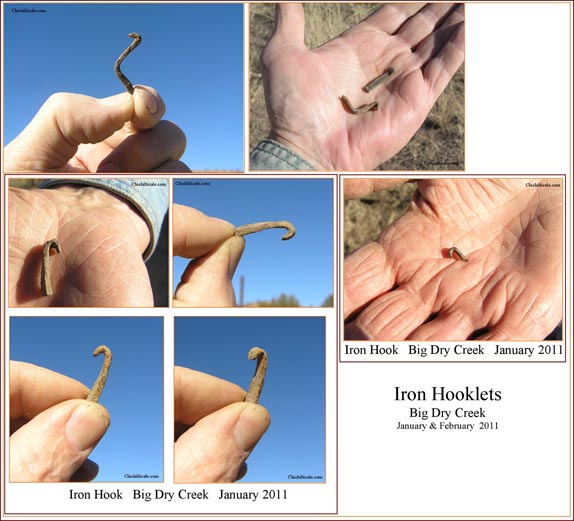

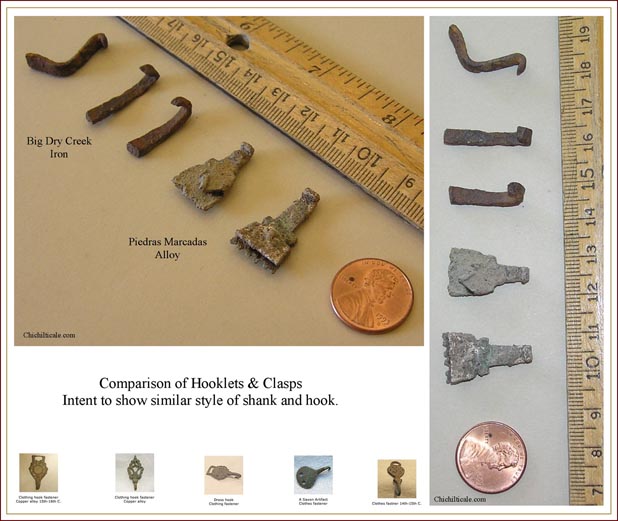

On the topographic bench on the Sutton property about 800 feet west of the aglet and dome-head tack we found an area measuring 18' x 16' immediately beside the cutbank that contained a cluster of iron artifacts. Two of these pieces were forged iron, dome-head tacks identical to the one found near the aglet. Also within the cluster were two small forged iron handles, two forged iron chain links, and five forged iron elongate “hooklets” of similar form, function and craftsmanship. Two hundred eighty feet west we found another elongate hooklet like those within the cluster. Seventy feet northeast of the cluster we discovered a forged iron nail.

Professional blacksmith, Spanish colonial horse tack authority and author Frank Turley of Santa Fe examined the iron pieces and reported that “all the items appear to be forged” from bloomery iron, which fell into disuse by the time of the American Civil War. About the chain links, handles, forged nail, and hooklets Turley wrote:

"[At first glance] these [chain links] appear to be preparation for a link. When small links are made, they are flattened on the ends (scarfed) and closed together. They can be brazed with brass or copper. In re-thinking about the two links, they may not be preparations for closing. They are probably broken links. You can see the so-called, flattened scarfs of the wire ends, where they would have met and probably been brazed. The links are probably old, colonial Hispanic, because they used such links for rein chains and for curb chains (the small chain that would go in the horse's chin groove, if the horse was not wearing a ring bit.) These could be handles, but for something small. You can see two tiny stress splits on one of the small handles. It may have broken there at ambient temperature. [The forged nail] could have been used for a number of things... It is easier to forge a square nail than a round one, and it is stronger. [The hooklets] look like horseshoe nail shanks with the clinches, the bent end portions, still showing. I cannot account for the fact that the nail heads are missing, if that is the case. The reasons for these pieces are unknown to me.”(31)

We consider the dome-head tacks alone to be strong evidence of Coronado. Because of the presence of these tacks within the cluster, it is not prudent to eliminate the chain links, handles and elongate hooklets as being Coronado artifacts also. Just as significant, the large forged wrought nail recovered near the cluster was the only one of its type found on the Minnie Bell site, and an almost identical nail was recovered at Piedras Marcadas. The totality of these circumstances supports a Coronado source for the pieces.

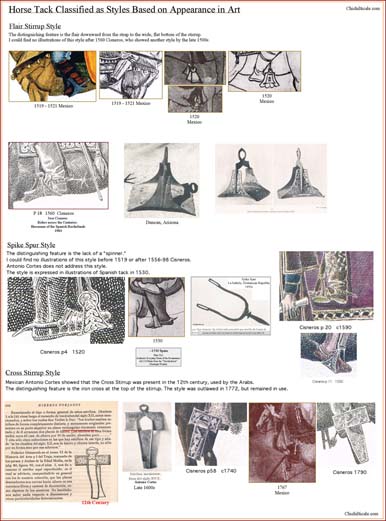

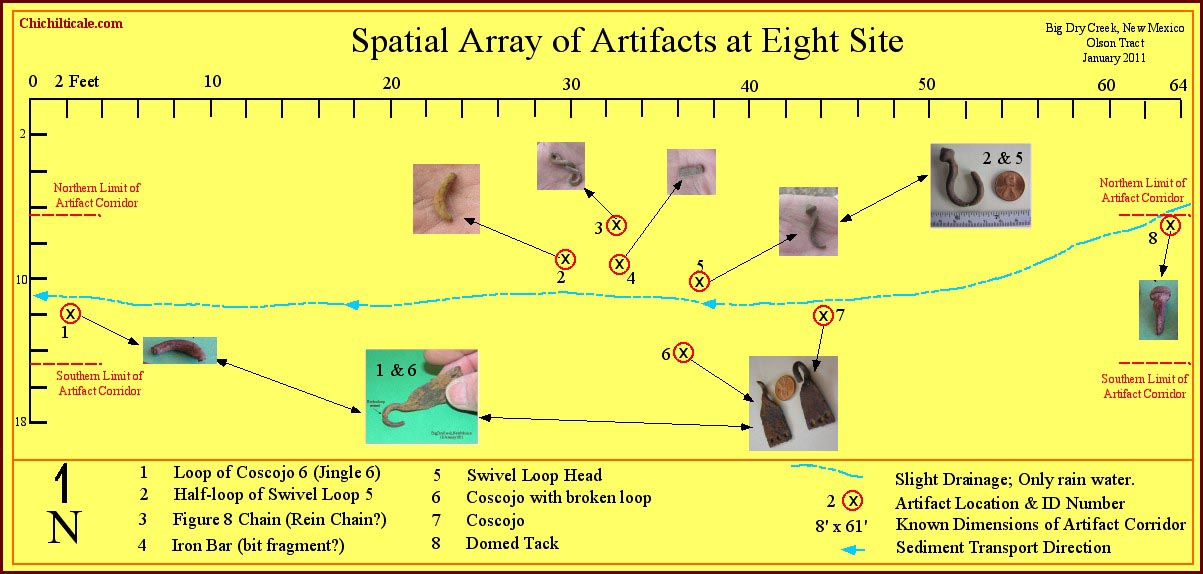

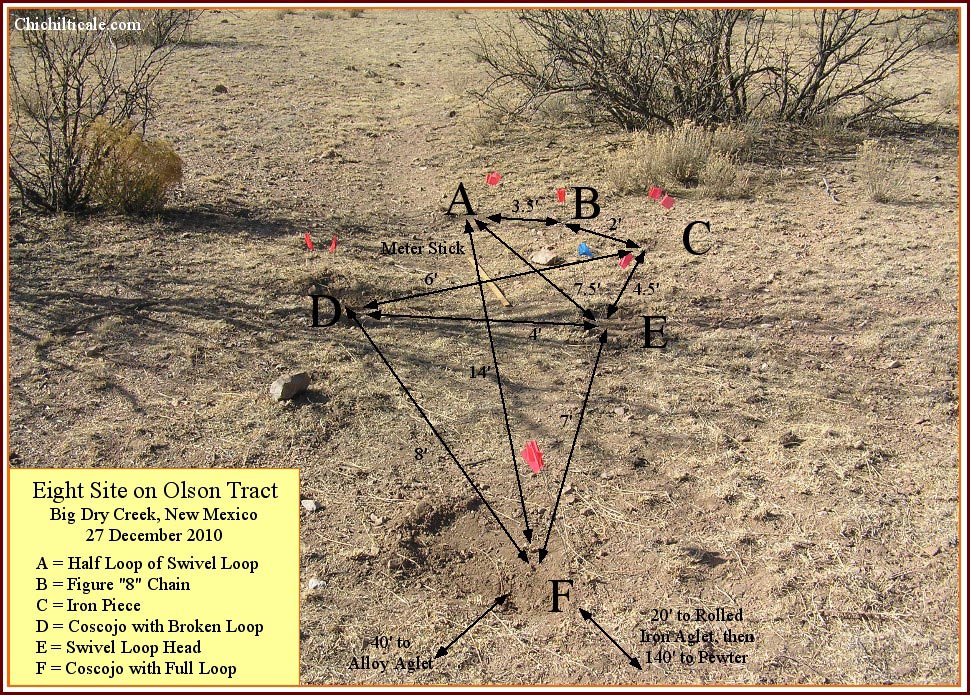

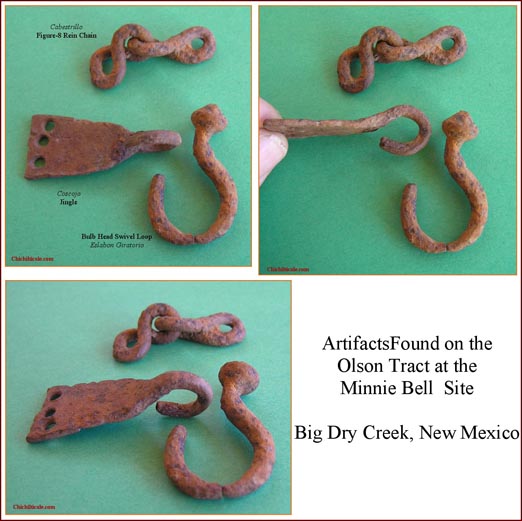

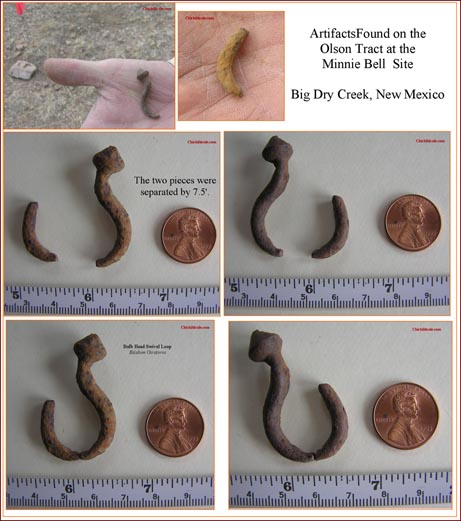

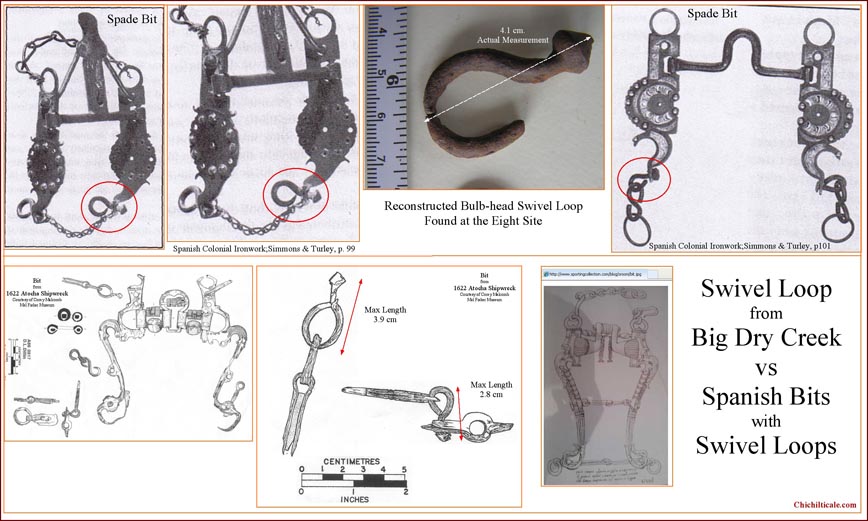

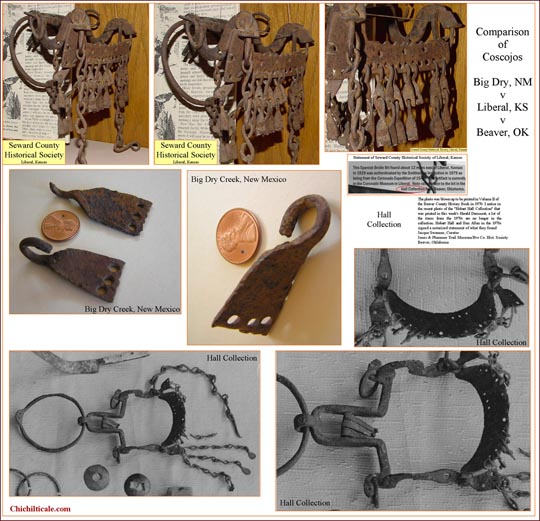

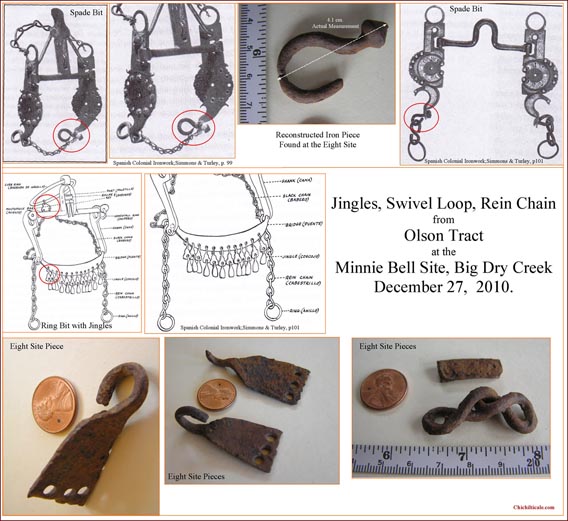

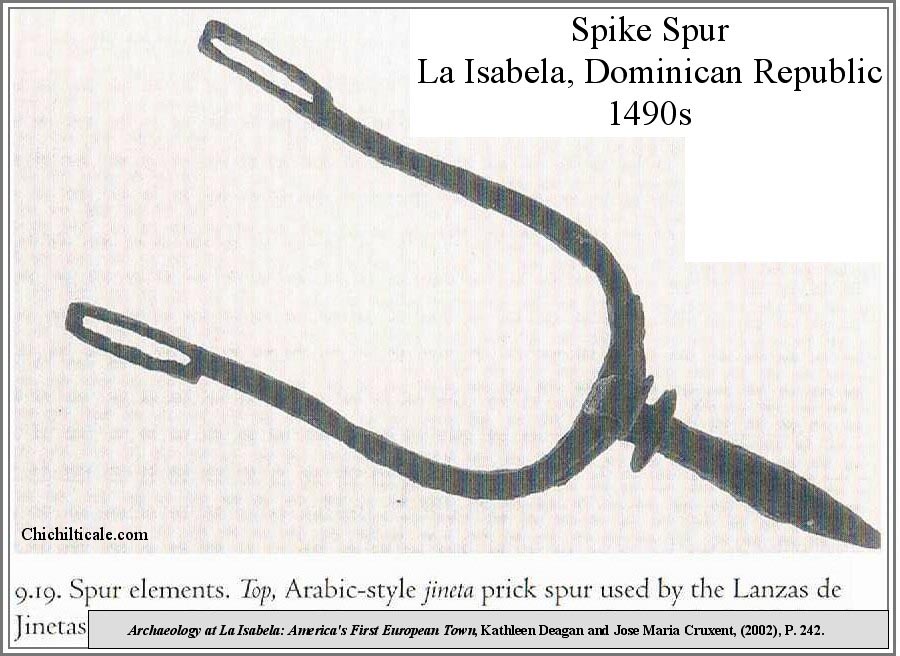

Within a 14’ by 7’ cluster on the topographic bench 160 feet west of the pewter medallion, forty feet northwest of the copper alloy aglet and nineteen feet west of the dome-head tack, the team found five pieces of confidently identified iron horse tack and a single tentatively identified piece of tack. Twenty-seven feet down slope we found another piece of horse tack. All seven pieces lay in the same subtle drainage as had the dome-head tack found on the Olson tract. Included in the horse tack were two coscojos (jingles). One was intact, and the other was almost complete, as just the tip of the loop was broken off, which was recovered 27’ away. Also included in the artifact cluster was a bulb-head swivel loop from an eslabon giratorio. The loop was broken where most wear had occurred, and the head piece was found separated from the distal end of the loop by about seven feet. Two connected links of a figure-eight cabestrillo (rein chain) were found. A solid bar one inch long and 0.15" thick was found two feet from the chain; this piece has been tentatively identified as part of an asiento (mouthpiece bar).(32)

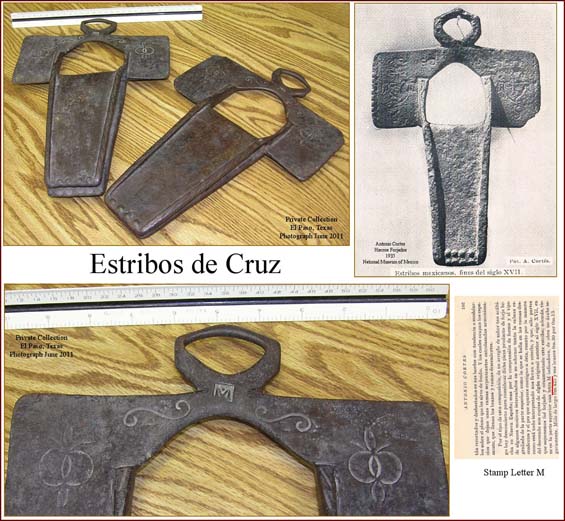

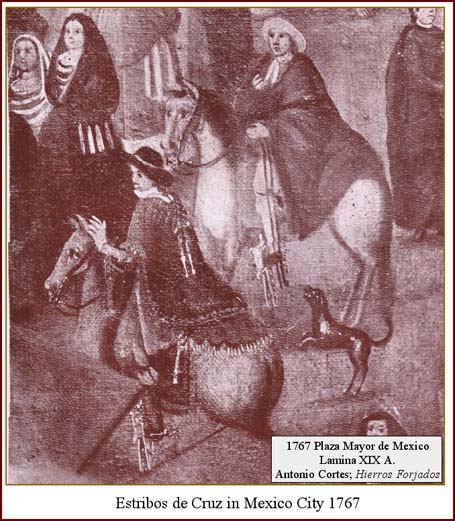

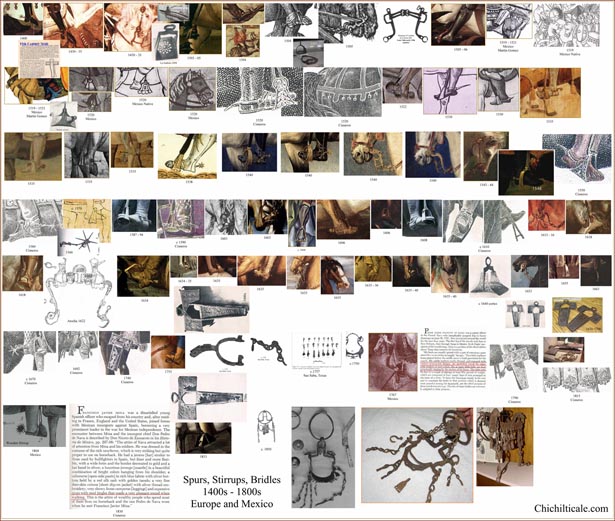

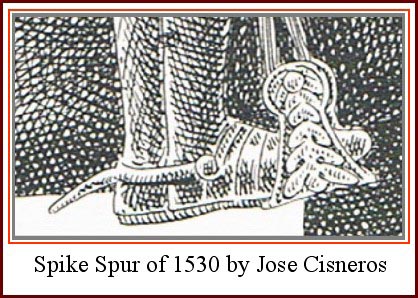

Our effort to assign a date to the horse tack included using data from the public domain to construct a database of artists, dates of their work, and copies of their paintings, sketches, etchings or sculptures of horse tack. Our database focused on the time span from AD 1400 to the twentieth-century. We added to this database by consulting with and visiting museums and private collectors. We obtained photographs from some museums, and we recorded our own images in other museums. We made direct, side-by-side comparisons of Big Dry Creek horse tack with pieces in these collections. We observed that the type of jingle, bulb-head swivel loop, rein chain, and mouthpiece bar recovered at the Minnie Bell site is on many pieces of horse tack found throughout the Southwest, California and Great Plains. The geographical expanse and the quantity of this type of horse tack suggest an association with a group more numerous and of longer duration than represented by the Coronado Expedition.

The team concluded that the pieces of iron tack were bearer-associated, and that the jingles offered the best temporal measurement of the complete tack assemblage. Coscojos are present in the collection at Presidio La Bahia, Goliad, Texas, but I remain uncertain that they date before 1749. Four score of jingles were recovered from the 1757-1770s San Sabá mission site at Menard, Texas, suggesting that they were in common usage by that time. Wandering French naval officer Pierre Marie Francois de Pages described jingles of 1767 as “trinkets of steel which, like as many little bells, are kept perpetually ringing by the motion of [the] horse.” Artist José Cisneros sketches jingles on a south Texas ranchero c. 1815. The New Mexico Spanish Colonial Arts Collection includes a nineteenth-century New Mexican ring bit with jingles. Our interpretation of the temporal range of jingles begins with their becoming stylish by c. 1750, and remaining so for about a century. This suggests that the tack could have arrived at the Minnie Bell site with Spaniards Menchero, Vildósola-Bustamante, Echeagaray or Zúñiga in 1747, 1756, 1788 or 1795. However, being as the Apaches were plundering well before 1747 and did so into the 1880s, the tack could also have arrived with those raiders.(33)

Adding to what must be considered when dating the horse tack is a conical rolled tin tinkler found twenty feet northeast of the assemblage. The tinkler is almost certainly of Apache manufacture and origin. Tin cans were first manufactured about 1810; this is likewise the date of the first patent of these items in England. The first American patent was granted in 1818. These first tin cans were hazardous if used for cooking in the can itself. By the middle of the nineteenth-century, however, the technology improved so that tin cans became omnipresent. Anthropologist John Cameron Greenleaf, now deceased, examined tin cans from the Johnny Ward Ranch, located next to Sonoita Creek west of Patagonia, in Santa Cruz county, Arizona. Ethnohistorian Bernard L. Fontana, lead author of the monograph containing Greenleaf’s work, suggested, “While it's theoretically possible Apache tin tinklers could date from the early 19th century, my guess is that they are more likely to date post 1850, by which time tin cans were becoming ubiquitous in the American West.” Whether or not the iron horse tack and the rolled tin tinkler are bearer-associated remains unknown. If they are bearer-related, then the iron tack is almost certainly of Apache origin because the tinkler dates no earlier than 1820, by which time the Spaniards had departed, and no later than 1886, by which time the Apaches had left the region.(34)

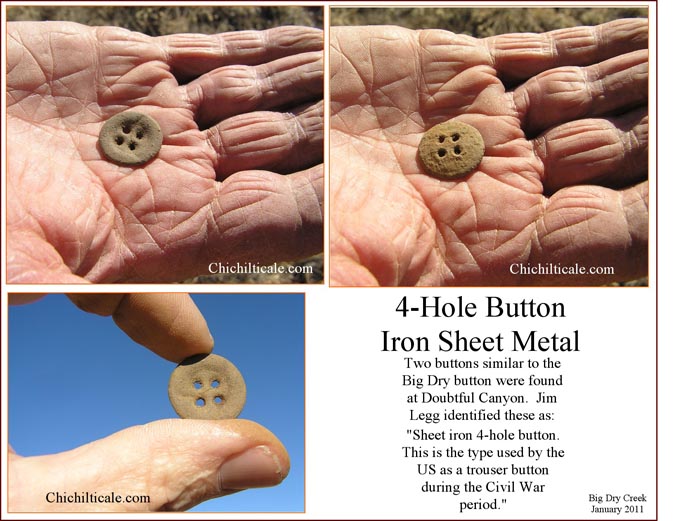

The team found three buttons on the western end of the topographic bench on the Sutton tract. One of these was a USM 1854 enlisted man’s button, the classic Federal button of the Civil War and into the 1870’s. Another was a sheet iron four-hole button used as a Federal military trouser button. These two buttons were most likely left at the site by the intermittent Federal military presence there from the 1870s into the late 1880s, but could also have come from a homesteader or traveler who wore military buttons. Another piece was an adorned, non-magnetic alloy, four-hole, self shank button that we have concluded was a civilian button from the homesteader era.(35)

Also found on the Sutton western topographic bench was a heavy brass grommet unlike contemporary grommets. We interpret that this piece was part of a tent or tarp. It could have arrived at the site with the Federal military, or the homesteaders, or with members of the Civilian Conservation Corps of the 1930s – 1940s who performed soil conservation work in the immediate area and lived in tents.

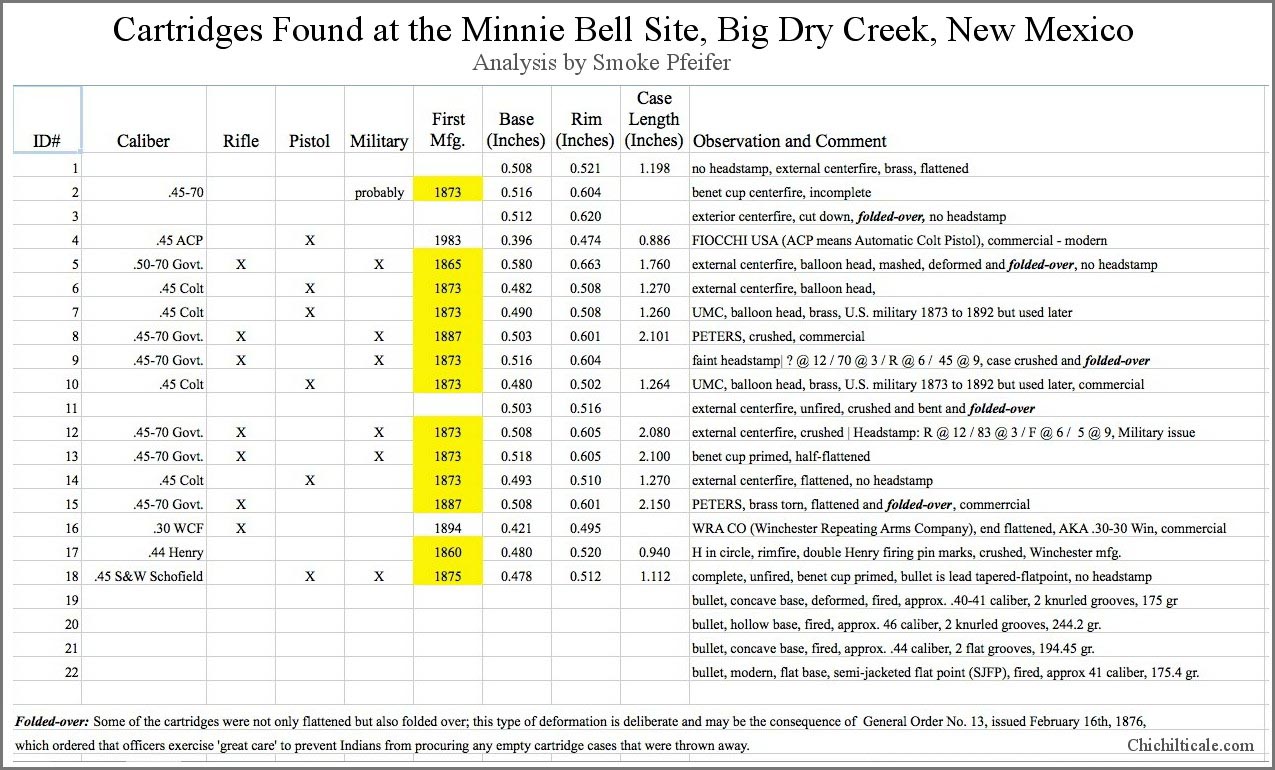

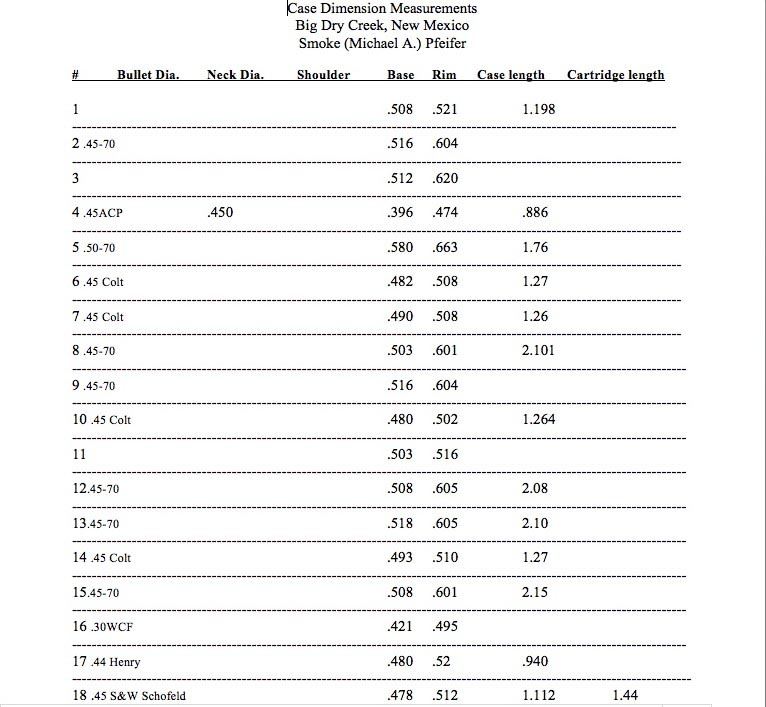

Numerous cartridge casings were found, including shotgun shells, 0.22 shells, and modern hunting shells. Of most interest to us were cartridges that could date from the nineteenth-century. We sent seventeen shell casings and one corroded unspent shell to ammunition expert Michael A. Pfeiffer of Russellville, Arkansas. Of the fifteen cartridges identified, the years of first manufacture of eleven casings dated 1860 to 1875 inclusive, and three dated 1887 to 1894 inclusive. We interpret these fifteen casings as being associated with the nineteenth-century Federal military presence and the earliest rancher Siggins and his cowboys.(36)

At the Minnie Bell site, Big Dry Creek serves as a township line, a county line and a property line. Tom and "Red" Humphreyville own private land on the south side of Big Dry, and they kindly granted us permission to explore there. Our preparatory field reconnaissance there had indicated Meader Hill to be a viable prospect. During May 2011 the team conducted a grid search of the Humphreyville property on this hilltop using a Blennert Sled and "swinging sticks." We found the surface essentially sterile of metal detector targets.(37)

Our reconnaissance had also shown us that the Humphreyville property contains a bench above the floodplain that represents the most favorable campsites for the 1540 Coronado Expedition. Unfortunately, this bench does not lend itself well to metal detecting exploration because the surface is rife with metal from the homesteader era of Lee, Meader, Snider and Hines. These adverse metal conditions forced us to avoid the bench and to focus our search on the slopes of the southern riser (low cutbank) and the wash from the bench through the riser, where in May 2011 we found one artifact of interest – an asidero (headstall ring on horse tack). Since we could find no evidence of the style prior to the middle 1700s, we consider the most likely bearer to have been a Spaniard of 1747, 1756, 1788, or 1795.(38)

West of the Sutton property on the north side of Big Dry Creek was land owned in 2010 by Hayden Forward. During the pilot metal detector survey on that land in June of that year, we found an iron awl buried directly beside a Mimbres black-on-white potsherd. We cannot assign an age to the awl.

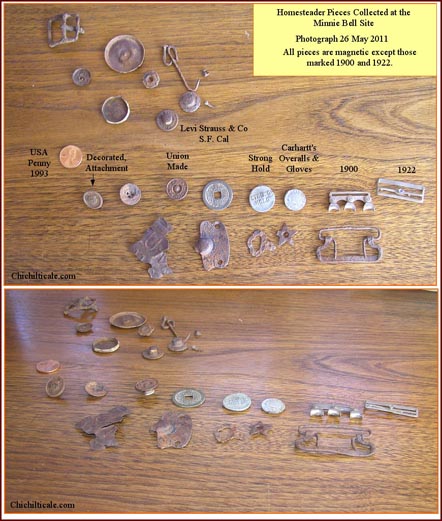

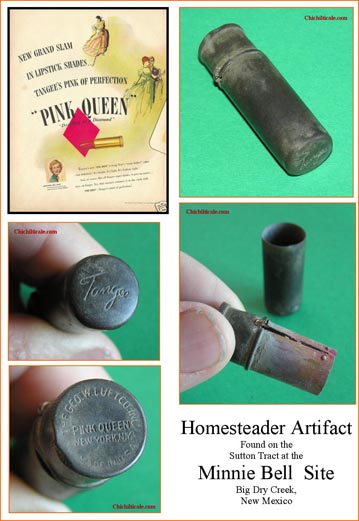

We observed copious quantities of homesteader material during our search of the Minnie Bell site, and these pieces were especially interesting to the namesake of the location. Minnie Bell studied, identified, and categorized the artifacts and provided a handwritten report to the author. Included in the collection were a flour sifter, potato masher, tin bowls, spoons, perforated spice jar top, jar lid locks, chicken grabber, stove parts, buckets, handles, key, door locks, hinges, ceramic door knob, broken glassware of dishes, lids, jars and bottles, pieces of iron pot-bellied kettles, lettered tin cans, bottle tops, buttons, pins, rivets, clock parts, lamp wick, metal rifle butt, buckles, chains, swivels, wagon parts, rubber tire scraper, screws, nuts, bolts, nails and tacks, chicken wire, hooks, springs, bedsteads, shaping hammer, axe, saw blades, horse tack, used flared horseshoes, boot heels, lipstick, nail file, and a harmonica.

These objects contributed to identification of post-Civil War artifacts by demonstrating what these early settlers possessed, thereby aiding us in judging what was NOT homesteader material. For example, flat-head homesteader tacks were distinct from dome-head tacks by their size, shape, and craftsmanship; cut nails and wire nails used by the homesteaders were common while forged nails were almost singular; homesteader chain was distinct from forged horse tack rein chain; homesteader wire handles were larger and unlike the forged, flared handles found in the cluster with the chain links and dome-head tacks. These comparisons elevate my confidence in our identification of Big Dry Creek artifacts.(39)

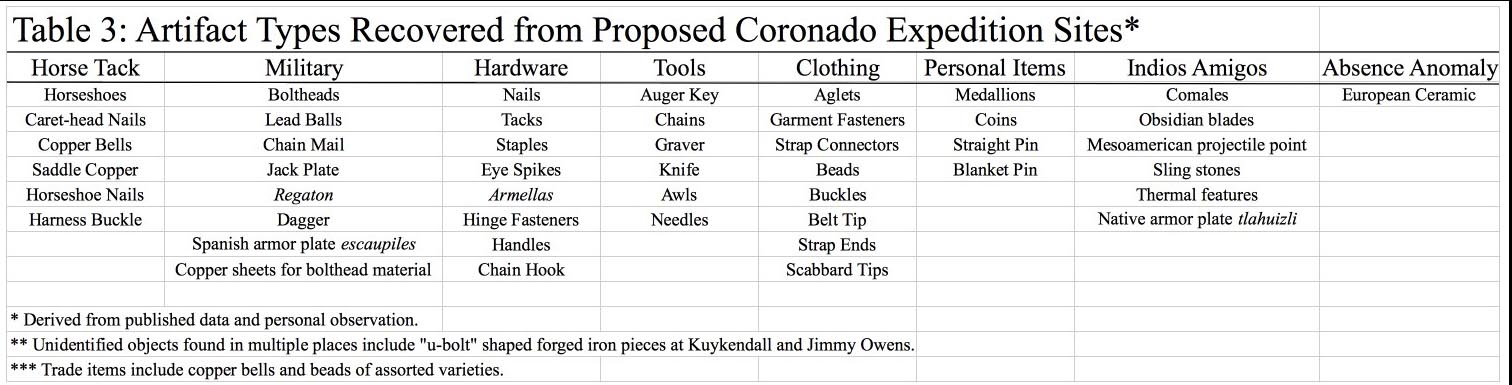

The Minnie Bell site artifacts that we assigned to the Coronado Expedition match well categorically with proposed Coronado pieces in the collections from Kuykendall Ruins, Doubtful Canyon, Hawikku, Kyakima, Santiago Pueblo, Piedras Marcadas, LA 54147 and Jimmy Owens.

Minnie Bell Henry Hudson facilitated the exploration at Big Dry Creek. She also introduced me to collectors and ranchers that contributed to this report and to the Coronado exploration program in its totality. Minnie Bell leaves a firm footprint on our understanding of the Coronado Trail.

Richard Flint, Shirley Cushing Flint, Carroll L. Riley, and Brent Locke Riley have contributed to and supported this exploration from its beginning in 2004. Cal said more than once, “We need to get him into the San Francisco Valley.” Our discovery at the Minnie Bell site suggests that we have.

Loro Lorentzen has contributed careful thought, analysis, and sweat labor to our exploration and is part of all the discoveries. Although not present at the Minnie Bell site, Dan Kaspar, John Blennert, and Gordon Fraser helped prepare us for our exploration at Big Dry Creek.

Editor Durwood Ball and the staff of the New Mexico Historical Review have been instrumental in publishing the reports of our exploration. I am especially grateful to Donna Schank Peterson, whose wordsmithing and organizational skills have made my reports the strongest they could be.

Without the cooperation of the landowners at Big Dry Creek, our exploration could not have happened. My warmest gratitude to them for “letting me on” their property. Jerry Jump and Kenny Sutton were especially accommodating.

Artifact identification continued as a group effort. Frank Turley contributed to and influenced mightily our conclusions about the iron and the iron artifacts found at Big Dry Creek. Matthew Schmader generously made available for examination and comparison the collection of artifacts recovered at Piedras Marcadas. Franco Marcantonio, geochemist at the Radiogenic Isotope Geochemistry Laboratory in the Department of Geology and Geophysics at Texas A&M University, and Nelia Dunbar, geochemist and manager of Electron Microprobe Lab, New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, Earth and Environmental Science Department, New Mexico Tech, provided technical expertise to the program. Smoke Pfeiffer contributed respected analysis and identification of cartridges found at the Minnie Bell site. I am grateful to John H. Madsen for sharing his Spanish colonial database, and for his longstanding contribution to Southwestern history. Nancy Marble of the Floyd County Historical Museum has supported and contributed to our exploration program from the beginning. On a broader scale, I recognize that the collectors, ranchers, professors and curators who have provided me access to their artifacts have played a paramount role in this exploration. They facilitated comparison of our pieces to those in their collections, thereby providing “look-alikes” that suggested comparable temporal artifacts, lending confidence to our conclusions about the presence or absence of the Coronado expedition. To all of them I send my warmest gratitude.

The Glenwood Community Library, especially Judy Truett, obtained through the inter-library loan system many of the books and documents referenced and consulted for this report. Adding to this support were Ken Dayer at the Silver City Library, Tom Hester at Historical Research in the Silver City Museum. Ann Massmann and Nancy Brown-Martinez at the Center for Southwest Research kindly provided the Spanish documents pertaining to the Menchero and Celís adventures. John Kessell kindly shared information on where to find specific source documents.

For their counsel on various issues, I thank Bernard L. “Bunny” Fontana, Sarah Herr, Nancy Kenmotsu, Alan Ferg, Samuel Truett, and Karl Laumbach.

At the time this report was typeset in March 2013 we had no Coronado exploration in progress. Considering that this might be my final report, and that I might not get another chance in print, I want to remind Karen Whiteside Brasher how much she contributed to this adventure and to tell her again how much I love her.

(1) For various and conflicting accounts of the ambush at Soldier’s Hill and the death of surgeon Thomas John Claggett Maddox, see: William French, Some Recollections of a Western Ranchman, New Mexico 1883-1899; Argosy-Antiquarian,Ltd. (New York, 1965) 2 vol., p 111-15,v.1; William H. Mullane, Apache Raids: News about Indian activity in the Southwest as reported in The Silver City Enterprise November 1882 through August 1886; copyright 1968; The Southwest Sentinel, 22 December 1885 in “Soldier’s Hill,” information compiled by Terry Humble, p. 1, Silver City Public Library, Southwest History Drawer, Soldier’s Hill; James P. Finley, “Fort Huachuca and the Geronimo Campaign 1886,” in Huachuca Illustrated: A Magazine of the Fort Huachuca Museum; Volume 7, 1999, p. 55-56; James H. Cook, Fifty years on the Old Frontier, As Cowboy, Hunter, Guide, Scout, and Ranchman; Yale University Press (New Haven, 1923) 182; Jerry Eagan, “Studying the Ground: Searching for Soldier’s Hill, site of a renowned Apache ambush in 1885” in Desert Exposure, February 2007; H. W. Daly. “The Geronimo Campaign,” Journal of U. S. Cavalry Association, vol. 19 (1908), 247-262. Some reports describe Maddox as “dismounting” after being shot, and speaking to Babcock or Lieutenant Cabell before suffering the fatal bullet. Military historian Jerry Eagan, however, reported that Maddox took a bullet in the chest and “came off his horse,” and that hospital steward Babcock and Private Beatty then attempted to get Maddox to cover, but the surgeon was shot in the back of his head. As for the reporters of the time, Fountain was not at the death site, and McKinney, who was present, did not report on the death, so no witness who was actually at Maddox’s demise reported on that event. French’s account is as he later penned it per his recollection of the ambush as told him by Fountain that night. Fountain’s version of the death of Maddox likely comes from Babcock and Beatty. Fountain reported that all shots fired by the Apaches were within forty yards of the troops, suggesting that Maddox was shot at close range. Fountain described the tierra doblada landscape as “timber and rough land,” and French pointed out that “owing to the nature of the country and the steepness of the hills, it was necessary to travel several miles [to cover] less than half a mile.” French considered tierra doblada “impracticable for horses.” The Apaches withdrew by foot to the west toward the Río San Francisco.)

(2) I previously reported this exploration: “The current exploration model… route was predicted in January 2005 and remains in effect after two apparent affirmations [at Kuykendall Ruins and Doubtful Canyon] of the exploration model. Our current exploration proceeds along this trace.” As will be discussed in this report, a total of four affirmations of the exploration model, an increase of two, are now proposed. Nugent Brasher, “Francisco Vázquez de Coronado at Doubtful Canyon and on the Trail North: The 2011 Report Including Lead Isotopes, Artifact Interpretation, and Camp Description,” New Mexico Historical Review 86 (summer 2011): 347.)

(3) Juan Jaramillo, “Juan Jaramillo’s Narrative,” in Documents of the Coronado Expedition, 1539-1542: "They Were Not Familiar with His Majesty, nor Did They Wish to be His Subjects," ed., and trans., Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 2005): 520; Nugent Brasher, “The Coronado Exploration Program: A Narrative of the Search for the Captain General,” in The Latest Word from 1540: People, Places, and Portrayals of the Coronado Expedition, ed. Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011), 243.)

(4) I have previously reported this route. See: Nugent Brasher, “The Coronado Exploration Program: A Narrative of the Search for the Captain General,” in The Latest Word from 1540: People, Places, and Portrayals of the Coronado Expedition, ed. Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011), 243-246; Nugent Brasher, “Francisco Vázquez de Coronado at Doubtful Canyon and on the Trail North: The 2011 Report Including Lead Isotopes, Artifact Interpretation, and Camp Description,” New Mexico Historical Review 86 (summer 2011): 342 Map 2, 347, 369 n.30. The deeply incised landscape of tierra doblada results from the erosion of coarse, friable Quaternary volcanic sediments existing as pediment gravels, colluvium, valley alluvium, and terrace gravels. The easily eroded terrain exists as a wedge between the steep western walls of the Río San Francisco on the west and, on the east, the Bursam Caldera of the northwestern side of the Gila Wilderness in the Mogollon Mountains. Cedar Breaks topography extends from Little Dry Creek on the south to the Río San Francisco on the north. Cedar trees, considered to be intrusive and uncommon in 1540, dominate the vegetation within the Breaks. For a discussion of this geology, see: James C. Ratté and David L. Gaskill, Reconnaissance Geologic Map of the Gila Wilderness Study Area, Southwestern New Mexico, Map I-886; U. S. Geological Survey, Reston, Va., 1975.)

(5) Nugent Brasher, “The Chichilticale Camp of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado: The Search for the Red House,” New Mexico Historical Review 82 (fall 2007): 433–68; "The Red House Camp and the Captain General: The 2009 Report on the Coronado Expedition Campsite of Chichilticale," New Mexico Historical Review 84 (winter 2009): 1-64; "Spanish Lead Shot of the Coronado Expedition: A Progress Report on Isotope Analysis of Lead from Five Sites," New Mexico Historical Review 85 (winter 2010): 79-81; “Francisco Vázquez de Coronado at Doubtful Canyon and on the Trail North: The 2011 Report Including Lead Isotopes, Artifact Interpretation, and Camp Description,” New Mexico Historical Review 86 (summer 2011):325-75; “The Coronado Exploration Program: A Narrative of the Search for the Captain General,” in The Latest Word from 1540: People, Places, and Portrayals of the Coronado Expedition, ed. Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011), 229-61. I reported this discovery at Big Dry Creek in Brasher, “Francisco Vázquez de Coronado at Doubtful Canyon,” 2011, 369 n. 30. Regrettably, the legend of Map 3 of my 2011 report contains an error: the trail symbol for the Coronado Trail is incorrect; readers should know that the Coronado Trail passed through Tarasca.)

(6) Minnie Bell Hudson, Home on the Range: Her Story & Recipe Roundup (Payson, AZ: Git A Rope! Publishing, Inc, 2006. For a comment by Minnie Bell concerning where the Coronado Expedition could have climbed onto the Mogollon Rim, see: Nugent Brasher, “The Coronado Exploration Program: A Narrative of the Search for the Captain General,” in The Latest Word from 1540: People, Places, and Portrayals of the Coronado Expedition, ed. Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011), 235.)

(7) Minnie Bell, Karen Brasher and I set out to trace the old wagon road. We started at Soldier’s Hill. Minnie Bell knew the road was there because her neighbor Jess Hines, who had helped build the unpaved vehicle road during the 1920s, knew the site. He had found cartridges from the Soldier's Hill ambush, and he had taken Minnie Bell, who was then only a little girl, to the spot to show and tell the local history. The wagon road descended from Soldier’s Hill through a natural cut to drop into a basin of eroded topography. The old road followed the path of least resistance for wheels, and the route was sometimes outlined with rocks on each side, appearing like particular portions of the Butterfield Trail in Doubtful Canyon. Off the trace was “up-and-down” tierra doblada, terrain to be avoided by herds of Coronado livestock. The contemporary game trail followed the wagon road. Subtle signs, such as gentle cuts, shallow ruts, unexpected level spots, and broken lines of rocks revealed the old road. Along the road itself was "trail trash" – parts of wagons, carriage bolts, horseshoes, decayed tin, broken crockery. These surprises seemed to be "out in the middle of nowhere" unless one recognized an old road. The wagon road we traced fits the description of the road location offered by late nineteenth-century rancher and historian William French, who had traveled the wagon road often. See: William French, Some Recollections of a Western Ranchman, New Mexico 1883-1899; Argosy-Antiquarian,Ltd. (New York, 1965) 2 vol., 112-19,v.1. The wagon road is shown on: United States Geological Survey, Mogollon, New Mexico Quadrangle, 1912. The actual Soldier’s Hill ambush site was been erased by the major landscape alteration of the modern highway.)

(8) Our dataset of prehistoric sites, extracted from the Archaeological Records Management Section (ARMS) Database in 2004, shows five individual masonry sites in the Slash SI prospect. Our own exploration has discovered eight prehistoric sites. For a description of our ARMS dataset, see: Nugent Brasher, “The Coronado Exploration Program: A Narrative of the Search for the Captain General,” in The Latest Word from 1540: People, Places, and Portrayals of the Coronado Expedition, ed. Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011), 239 Map 9.2, 258 Note 33. For locations of the eight prehistoric sites we have discovered on the Slash SI Prospect see Map 2. )

(9) Nugent Brasher, “The Coronado Exploration Program: A Narrative of the Search for the Captain General,” in The Latest Word from 1540: People, Places, and Portrayals of the Coronado Expedition, ed. Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011), 239 map 9.2; Despoblado is best described as unsettled land in preference to uninhabited land. A despoblado does not require the vacancy of humans, rather the vacancy of long-term settlements. Historian and Coronado authority Richard Flint wrote, “Consistently, early modern Spanish usage of "despoblado" is for reference to areas lacking sedentary populations (although there may have been nomadic or semi-nomadic populations in those very same territories). Despoblado is unsettled land without evidence of permanent human presence." Email to author 5 Jan 2012 from Richard Flint.)

(10) Don Juan Bautista de Anza, Governor of New Mexico, referred to this adventure as the “Great Campaign” in a 1 November 1779 letter to Commander-General El Cavallero de Croix, as did Croix’s assessor Pedro Galindo Navarro in a letter dated 28 July 1780 to Croix. Both letters mistakenly claimed the adventure occurred in 1749 rather than 1747. (Alfred Barnaby Thomas, Forgotten Frontiers: A Study of the Spanish Indian Policy of Don Juan Bautista de Anza, Governor of New Mexico 1777-1787 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1932): 173, 181.) For the original statement concerning the Celís adventure, see: Report of Alonso Victores Rubí de Celís of an Expedition Against the Gila Apaches, December 6-26, 1747, document 483, Center for Southwest Research, Albuquerque. Bishop Dr. Pedro Tamarón y Romeral reported on the campaign; for that account see Eleanor D. Adams, “Bishop Tamaron’s Visitation of New Mexico, 1760,” Historical Society of New Mexico, Vol. XV, February 1954, p. 89. For an overview of the campaign, see: John L. Kessell, “Campaigning on the Upper Gila,” New Mexico Historical Review XLVI, No. 2 (April 1971): 135-39; Marc Simmons, “Attempts to Open a New Mexico-Sonora Road,” Arizona and The West, V. 17, No. 1 (Spring 1975) p 9-10, map. The Saliz Mountains lie on the western side of the Río San Francisco between Spurgeon Mesa and Reserve. Federal highway 180 ascends the western side of these mountains and crosses the highest road elevation at Saliz Pass. The Great Campaign passed through this immediate area. The local pronunciation of Saliz is essentially the same as the Spanish pronunciation of Celís, suggesting the origin of the place name.)

(11) Translation by Richard Flint. Original source Biblioteca Nacional, Mexico, Archivo Franciscano, leg. 10, nos. 28a and 61, copy from Center for Southwest Research, Albuquerque. Readers can find a previous translation of the Escalante letter in Alfred Barnaby Thomas, Forgotten Frontiers: A Study of the Spanish Indian Policy of Don Juan Bautista de Anza, Governor of New Mexico 1777-1787 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1932): 155-56. Additional comments pertaining to the 1747 expedition, mistakenly identified as 1749, are on pages 173 and 181 of that volume. Also in his 1775 letter, Escalante mentioned a 1754 military excursion south of Zuni, but I interpret that this party did not reach Big Dry Creek. Support for the claim that the Río San Francisco was named during the Great Campaign of 1747 comes from examination of maps provided by archaeologist Peter L. Eidenbach. His map presentation shows that prior to Miera’s 1758 map, the Río San Francisco remained unnamed; in 1758, after the Campaign, Miera shows the named river. Peter L. Eidenbach, An Atlas of Historic New Mexico Maps, 1550-1941 (University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, 2012) 40.)

(12) I consider the Río Tularosa to be Coronado’s Río Frío. Coronado’s famous crossing of the Río Balsas occurred at the Río San Francisco at Alma, where that river is not contained within box canyons. For a discussion of that crossing, see: Nugent Brasher, “The Coronado Exploration Program: A Narrative of the Search for the Captain General,” in The Latest Word from 1540: People, Places, and Portrayals of the Coronado Expedition, ed. Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011), 245-47. I am grateful to Anza trail historian Joe Myers, who directed my attention in February 2012 to Escalante’s letter after recognizing the Río Tularosa in the description. John Kessell, as well as historian Marc Simmons, each presented maps showing their interpretation of the campaign’s route, which included passing by Big Dry Creek. (John L. Kessell, “Campaigning on the Upper Gila,” New Mexico Historical Review XLVI, No. 2 (April 1971): map 141; Marc Simmons, “Attempts to Open a New Mexico-Sonora Road,” Arizona and The West, V. 17, No. 1 (Spring 1975) p 9-10, map.)

(13) John L. Kessell, “Campaigning on the Upper Gila,” New Mexico Historical Review XLVI, No. 2 (April 1971): 146-47)

(14) Nugent Brasher, "The Red House Camp and the Captain General: The 2009 Report on the Coronado Expedition Campsite of Chichilticale," New Mexico Historical Review 84 (winter 2009): 44-5; “Francisco Vázquez de Coronado at Doubtful Canyon and on the Trail North: The 2011 Report Including Lead Isotopes, Artifact Interpretation, and Camp Description,” New Mexico Historical Review 86 (summer 2011):355-56; José de Zúñiga, “Una expedición militar de Tucson (Arizona) a Zuñi (Nuevo México),” in La España ilustrada en el Lejano Oeste: viajes y exploraciónes por las provincias y territorios hispánicos de Norteamérica en el siglo XVIII, ed. Amando Represa, Estudios de historia (Valladolid, Spain: Junta de Castilla y León, Consejería de Cultura y Bienstar Social, 1990), 89–100. Represa incorrectly reports the year of the expedition as 1791; the actual year was 1795. The count of 280 leatherjackets and 120 presidio men is from George P. Hammond, "The Zúñiga Journal, Tucson to Santa Fé: The Opening of a Spanish trade Route, 1788-1795," New Mexico Historical Review 6, 1 (1931): 40-65. Richard Flint pointed out that since presidial soldiers of that era all tended to wear cueras de anta, the distinction between leatherjacket and soldier is unexpected. With respect to the number in the Zúñiga party, Represo reports 151 soldiers and Apaches, while Hammond writes 140 soldiers and eight Apache scouts.)