Francisco Vázquez de Coronado at Doubtful Canyon and on the Trail North

The 2011 Report Including Lead Isotopes, Artifact Interpretation, and Camp Description

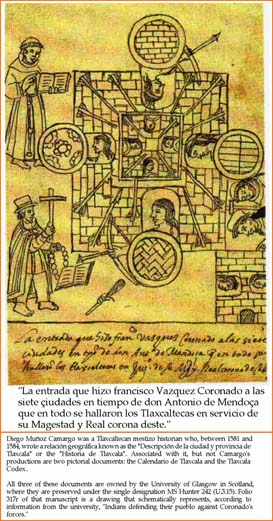

The Spaniards tell that Capt. García López de Cárdenas, maestre de campo of the advance party of the Coronado Expedition, with his small force of expeditionaries, reached the boulders in the Rio Zuni above Ceadro Spring at Dangerous Pass for the second time late on the Julian Tuesday of 6 July 1540. The force had first been sent there by Capt. Gen. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado to reconnoiter and report, and, based on what he heard, Coronado sent García López back to stand guard while the advance party remained camped at Río Bermejo. Under the cover of darkness enhanced by a nearly new moon, after a quarter of the second watch had passed, about a hundred warriors from Cíbola attacked the García López force. The warriors shot arrows into some of the horses and turned others loose. After the startled Spaniards had mounted their steeds, they drove the warriors away from Dangerous Pass. A messenger immediately galloped away to the Río Bermejo camp to apprise Coronado of what had happened. The brief skirmish resulted in García López later reporting that the Hawikku warriors "attacked like courageous men." In describing the reaction of the Spaniards, chronicler Pedro de Castañeda de Nájera, not an eye witness, was bluntly harsh, reporting that some surprised soldiers were so disoriented that they put their saddles on backwards.

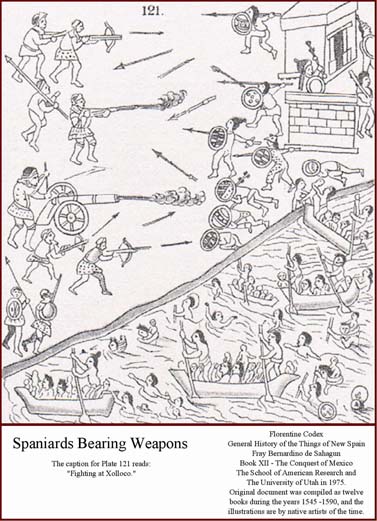

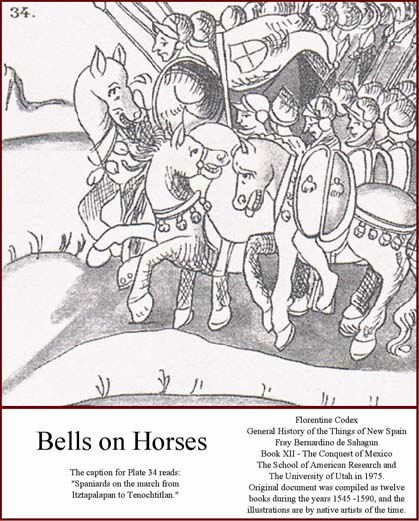

The following morning Coronado and most of his starving, fatigued troops moved out in the best order they could, heading toward Hawikku, periodically seeing smoke clouds alerting the warriors of the Spaniard's location. Once the invading "Men-in-metal" army reached the expansive flats southwest of Hawikku, Coronado dispatched Capts. García López and Melchior Pérez, friars Juan de Padilla, Luis de Úbeda, and Daniel, scribe Hernando Bermejo, and some horsemen as an advance group with orders to deliver the revered requerimeinto. Fray Marcos de Niza did not accompany the clerics because he was cloistered in protective custody to safeguard him from the likelihood of receiving an intentionally stray arquebus ball shot by one of the many expeditionaries angered by his false reports. After seeing that the advance group was welcomed by nothing but flying arrows, Coronado, bearing trade goods and accompanied by some horsemen, joined García López and the others at a location about a crossbow shot distance from Hawikku. The gilded metal man and the gray robes failed to engender homage from the warriors. During the second reading of the requerimeinto, the captains and the clerics were confronted by several hundred homeland defenders bearing shields and weapons who threw dirt and stones at the Men-in-metal, and who marked lines on the ground to declare a boundary not to cross, and who sent a hail of arrows into the invaders, wounding horses and piercing the robe of one of the friars.

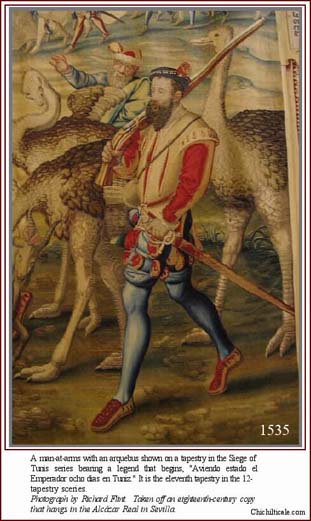

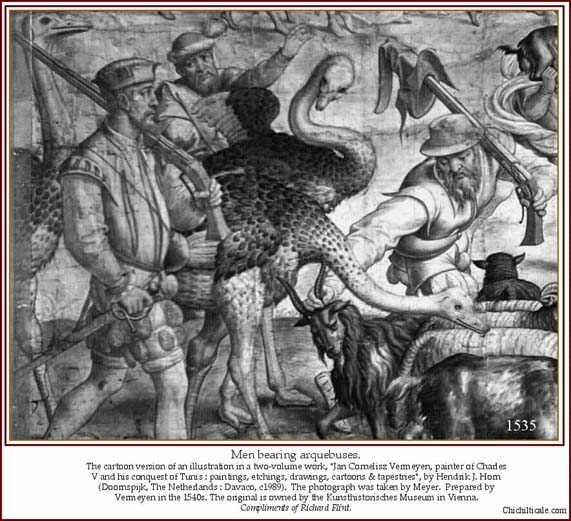

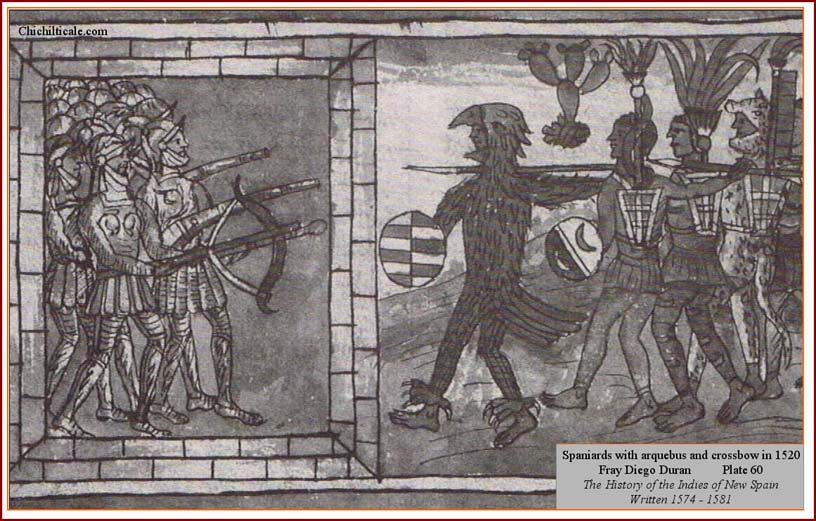

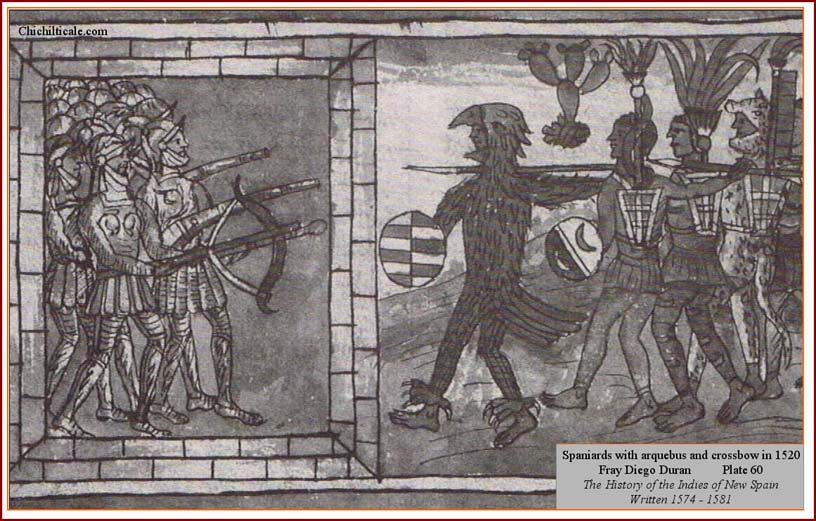

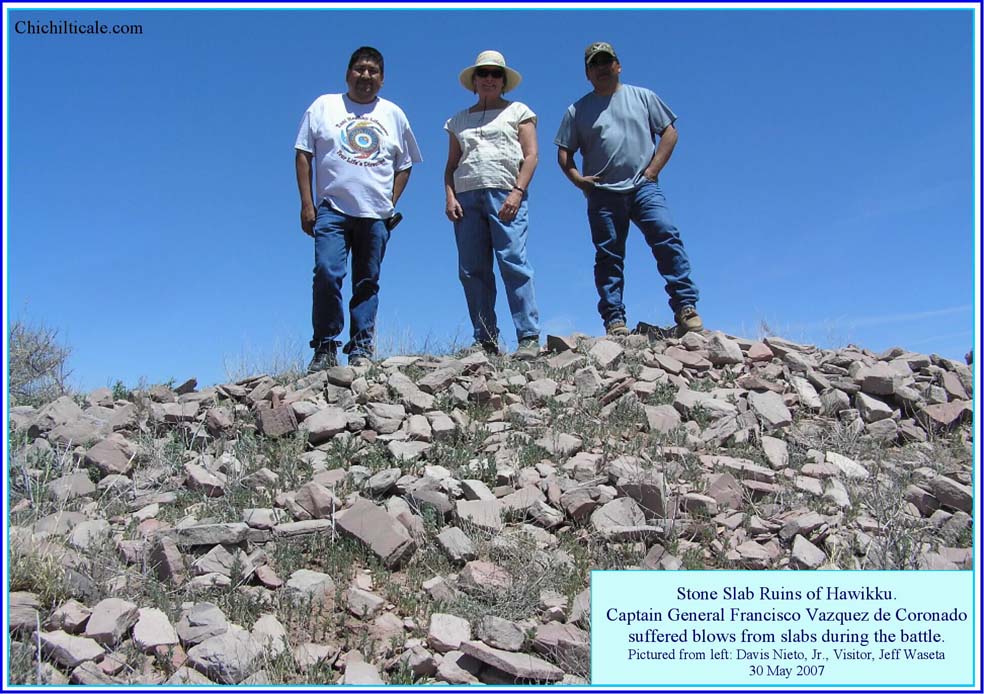

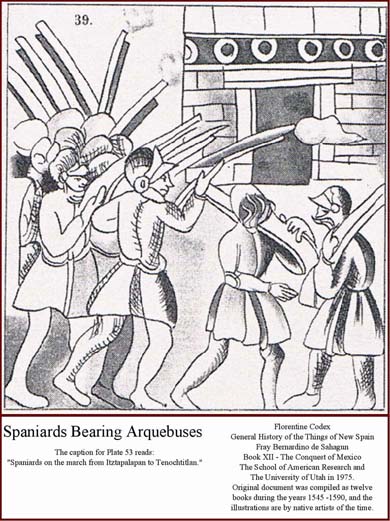

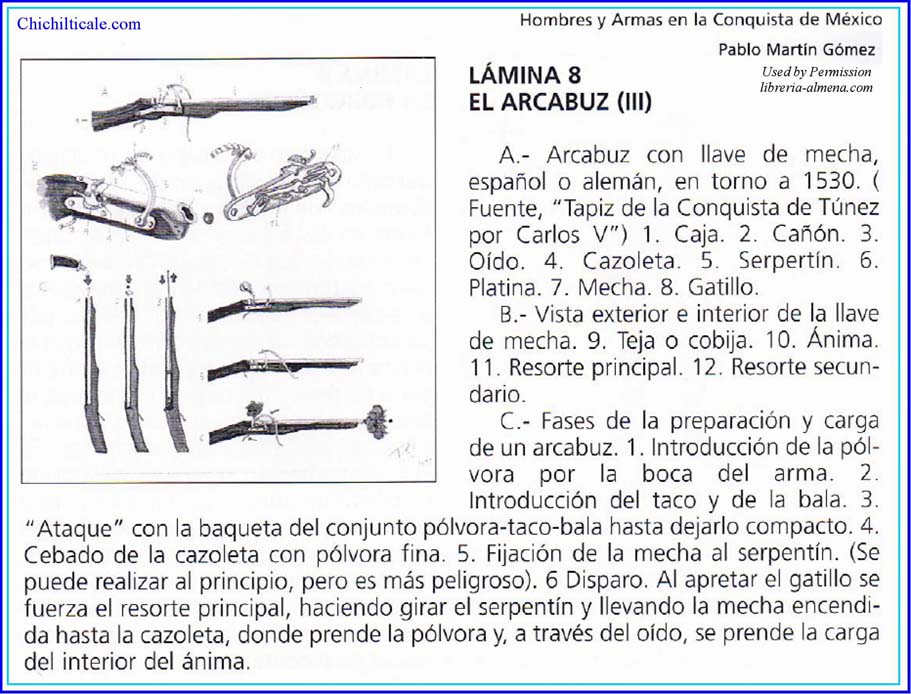

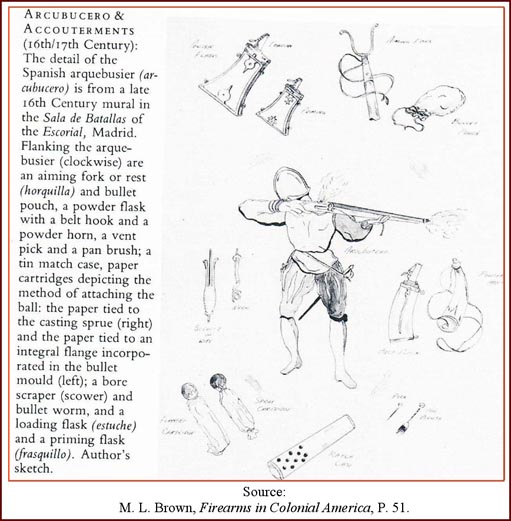

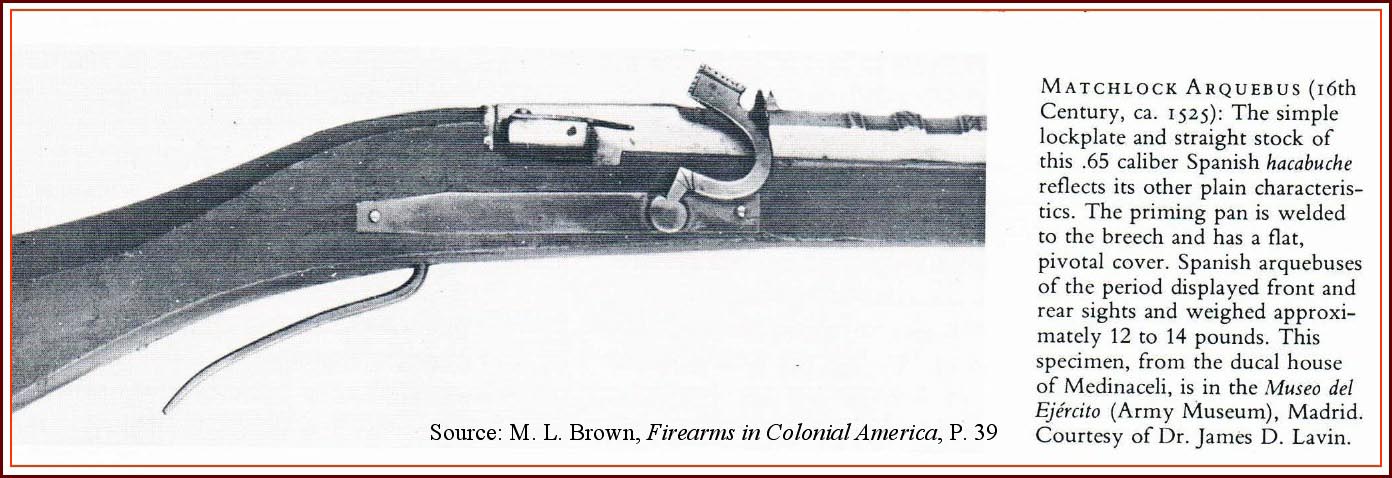

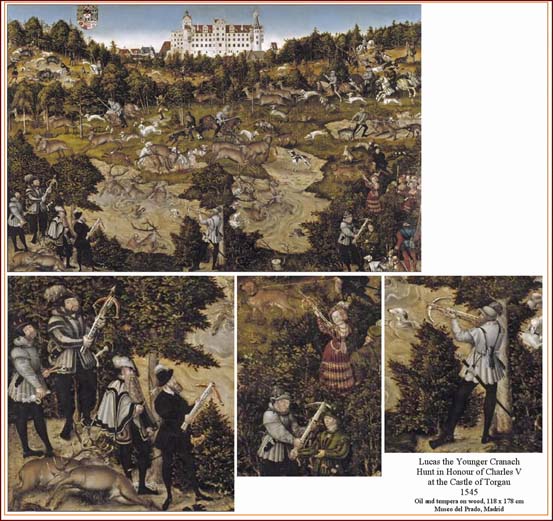

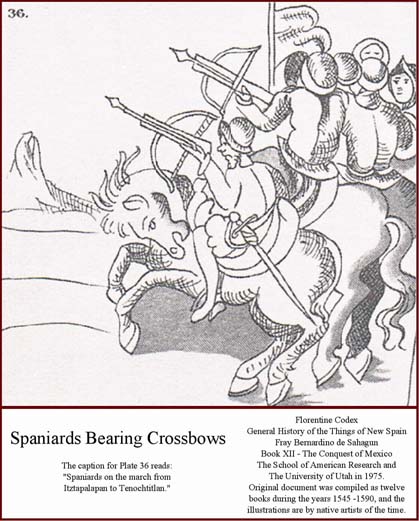

The Men-in-metal responded with a treble-phased attack. Mounted lancers first charged the defenders, who retreated into the walled pueblo of Hawikku, empty of women and children, all of whom had been evacuated to safety days before. Then the invaders approached the stone slab walls and again shouted the obligatory requerimeinto, all the while ducking arrows shot by the defenders atop Hawikku roofs. When the Men-in-metal rushed afoot to scale the walls, they were met by a barrage of rocks and arrows. The invader's crossbows proved ineffective because their bastard strings broke when distracted ballesteros hurried to cock their bows during the fracas, and their arquebuses proved too cumbersome to use in such close quarters. Repulsed by the homeland defenders, the Men-in-metal backed away from the walls and bombarded the pueblo with crossbow and arquebus projectiles. During the salvo of metal arrows and lead shot, the defenders cleverly slipped away from Hawikku in a planned retreat from the invaders.

The Captain General presented himself in flamboyant battle attire that 7 July 1540 day. His groom, Juan de Contreras, who lived inside Coronado's New Spain house and who ate with him, and who slept at the door to Coronado's tent, dressed the Captain General in brilliant, golden armor and with a fancy plume on his helmet. In this eye-catching habiliment, Coronado naturally became a marked man as he led the charge into Hawikku. After twice being knocked down by stone slabs slung by the defenders, Coronado was finally rendered inoperative when a sharp rock smacked him off a ladder as he tried to reach the flat roofs. The strike decorated his feathered helmet with a jagged dent and left him unconscious. The Capt. Gen. was hauled away and placed in a tent for about three hours, during which time befell the excitement of the light artillery fusillade and victorious seizure of Hawikku. Coronado suffered stone wounds on his head, shoulders, and legs, two facial gashes, and an arrow puncture in his right foot. His greatest trauma, however, was subsequent and emotional, when he realized that lying supine and unconscious in an improvised field hospital, he had missed the drama of the triumph at Cíbola. (1)

In addition to providing colorful history, the battle at Hawikku produced lead shot discharged from arquebuses. These nondescript artifacts contain isotope codes that can be measured and interpreted to predict the source of the lead used to mold the shot. I will show that the atomic signature of those little lead balls left at Hawikku and other locations mark the trail traveled by Coronado and his invaders.

Since September 2004, I have devoted my time almost exclusively to exploration for evidence of the 1540 – 1542 route of the expedition of Capt. Gen. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado between the international border with Mexico and Zuni Pueblo in New Mexico. During this time I formed an exploration team that remains active and experienced at the time of this writing. Three reports describing my team's methods and findings have been previously published by the New Mexico Historical Review. (2) This fourth report provides an account of the exploration program that is current to June 2010 Being that this paper will focus on new information, interested readers are encouraged to refer to the earlier publications as antecedent material.

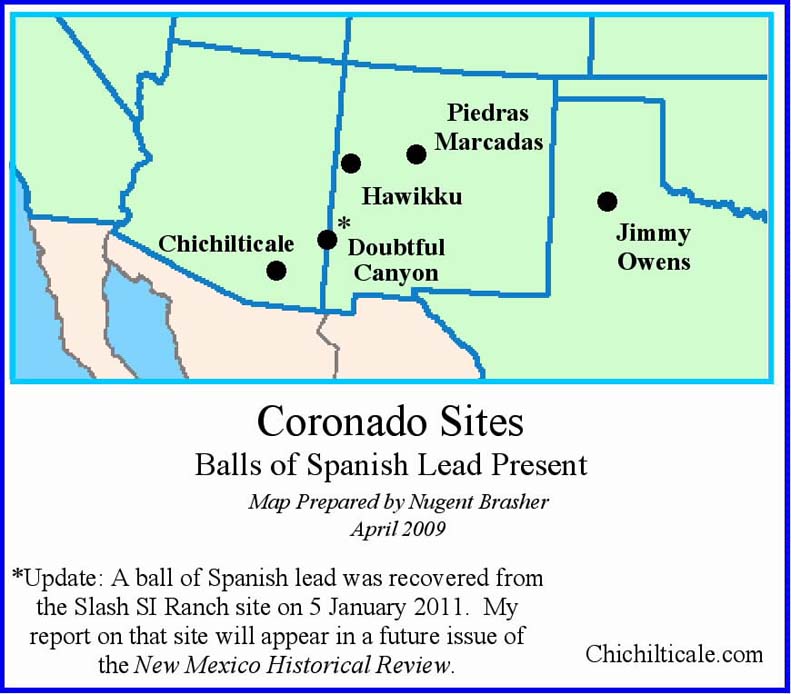

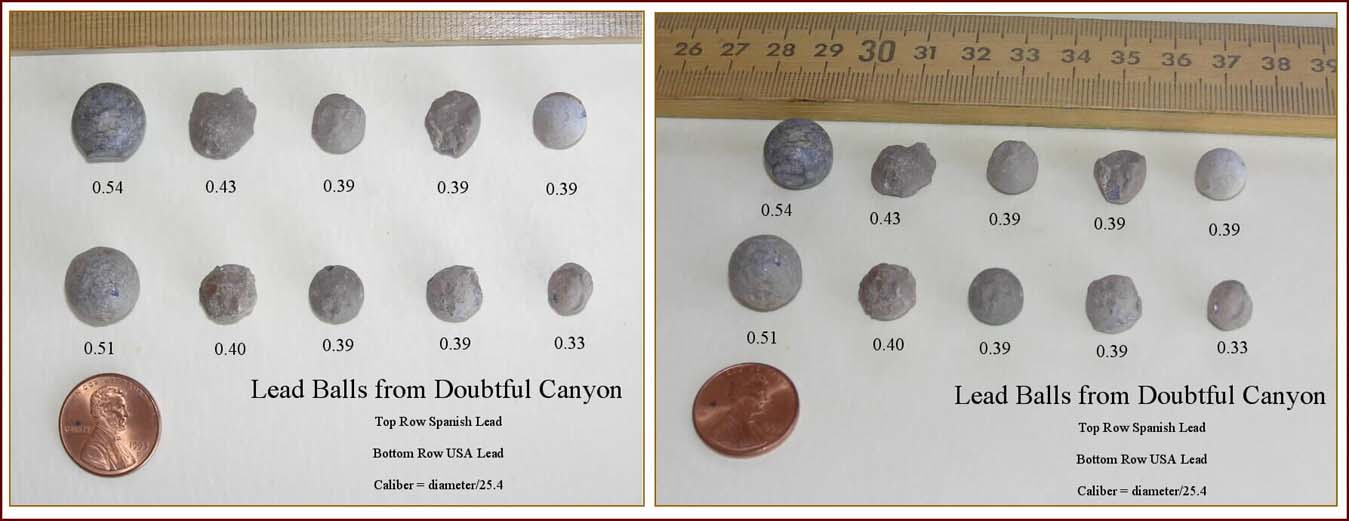

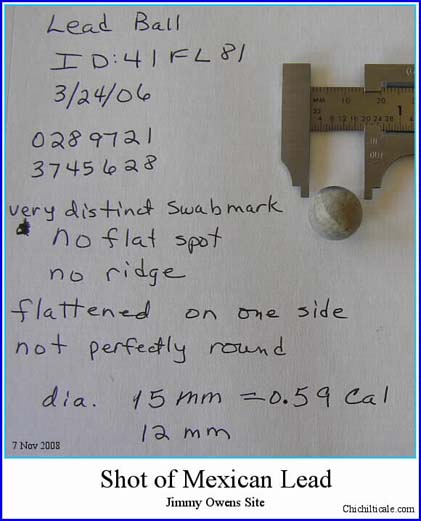

My 2009 report recommended that lead isotope ratios be obtained for four lead balls discovered at Kuykendall Ruins, and that these ratios be compared to ratios from lead shot found at other accepted or proposed Coronado sites. In 2010 I reported that geochemist Franco Marcantonio at the Radiogenic Isotope Geochemistry Laboratory in the Department of Geology and Geophysics at Texas A&M University used Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry (TIMS) to measure isotopes of lead shot from the suggested Coronado sites of Kuykendall Ruins (Chichilticale), Doubtful Canyon (Advance Party Camp 23 June 1540), Hawikku-Kyakima (Cíbola), and Jimmy Owens (the great hailstorm site in Blanco Canyon, Texas), and that I added to the dataset the isotope ratios presented by Charles M. Haecker for two lead shot found at the proposed Coronado site of Piedras Marcadas Pueblo in Tiguex (LA 290, Mann-Zuris site). In total the team measured or examined twenty-seven lead shot – four from Kuykendall Ruins, thirteen from Doubtful Canyon, four from Hawikku-Kyakima, four from Jimmy Owens, and two from Piedras Marcadas. Using published data I assembled a database of worldwide isotope ratios against which to compare my measurements. Following several robust statistical and visual analyses, the team determined that these twenty-seven shot were composed of lead from Spain, the Middle New World (herein defined as modern Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean Islands), and the United States.

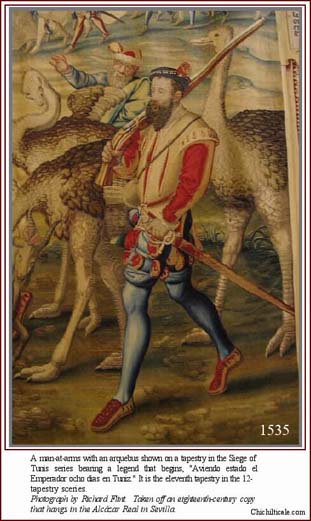

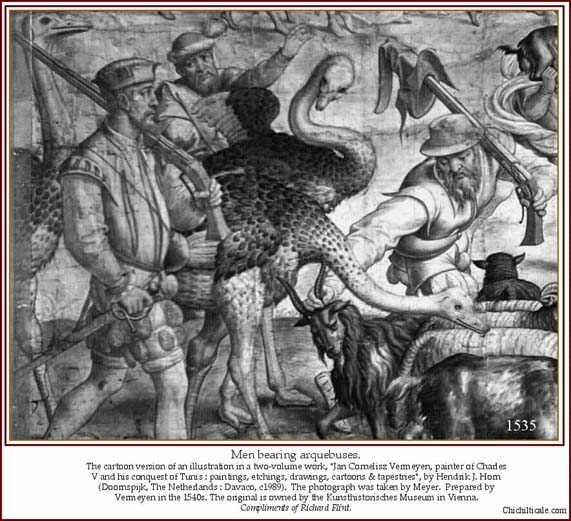

Of intriguing interest was that shot composed of Spanish lead sources were present at all five proposed Coronado camps. Written evidence supports firearms and their use by the Coronado Expedition. On 22 February 1540 in Compostela, "the muster was made of all the people going [with Capt. Gen. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado] to the land newly discovered." I counted twenty-six arquebuses in this muster. In addition to arquebuses fired at the battle of Hawikku, Pedro de Castañeda de Nájera reported that firing of these weapons occurred at the fracas on the Río del Tizón (Colorado River) where "the arquebusiers also were making good shots," and at the siege of Tiguex where Spaniards were "making good shots with arquebuses." Given the motive, means and opportunity for shot to be a product of the expedition, my team interpreted Spanish lead as representing a nexus among these five otherwise disparate locations, with the Coronado Trail being the common thread connecting all the sites. Moreover, I concluded that Spanish lead found within specific geographical corridors is diagnostic of the Coronado Expedition. Table 1 provides isotope ratios for ten lead shot my team determined were from Spanish source locations. Because my findings are best presented in colored, three-dimensional graphics, interested readers should view the methodology and supportive evidence contained in the section of this website titled "Lead Isotope Ratio Analysis.". (3)

My team found thirteen lead balls in Doubtful Canyon. Table 1 shows that five of these shot are composed of Spanish lead. I consider this Spanish shot to represent substantive members of the evidential body supporting the discovery of a Coronado campsite in that canyon. This discovery was predicted – my original exploration model of Coronado's route included his passage through Doubtful Canyon.

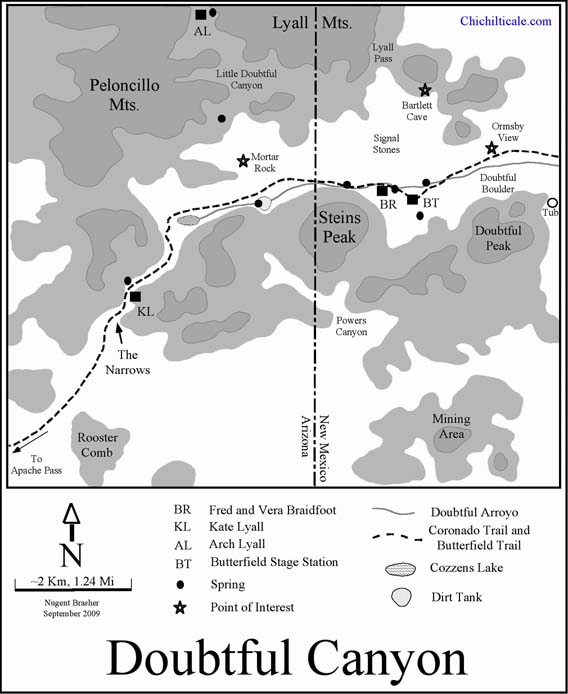

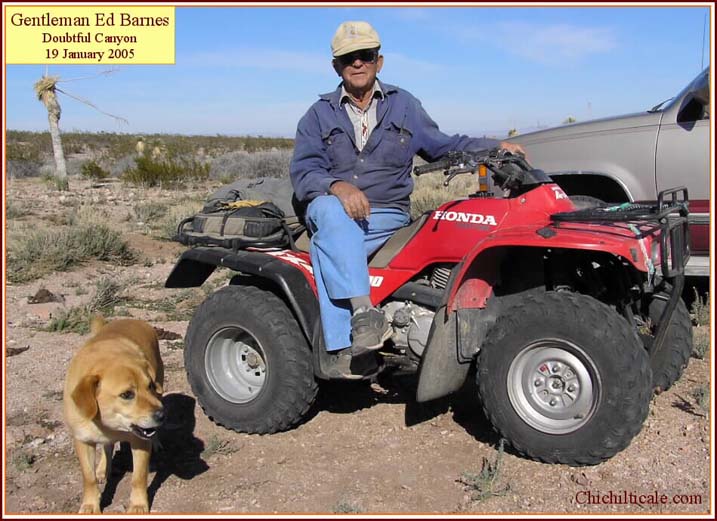

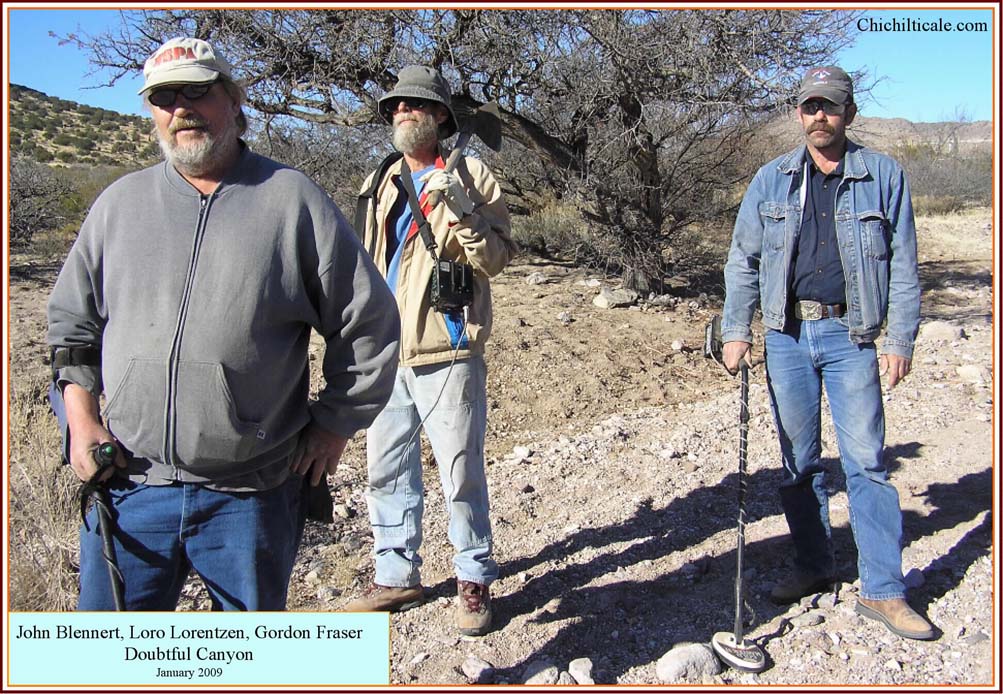

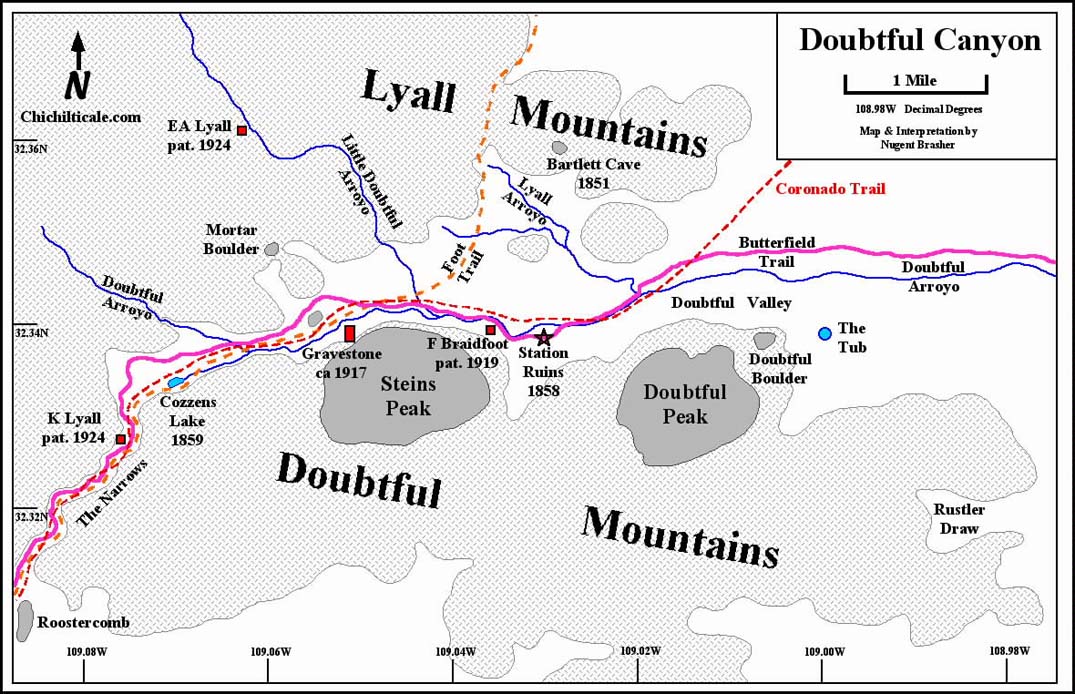

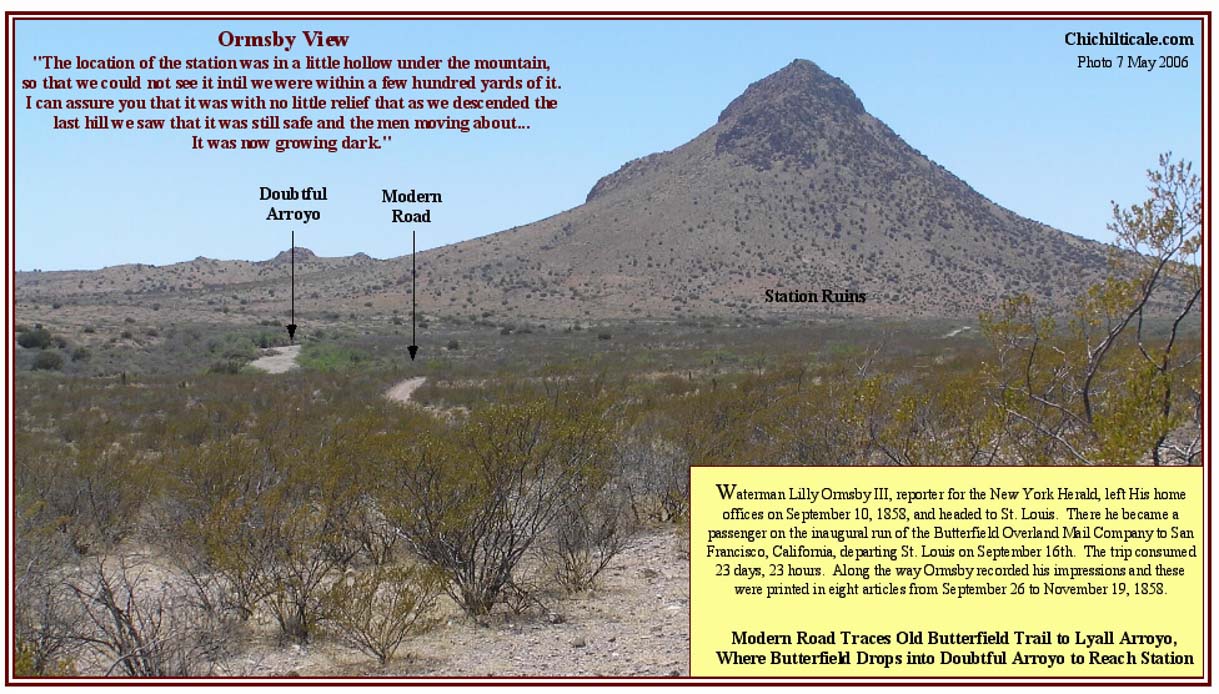

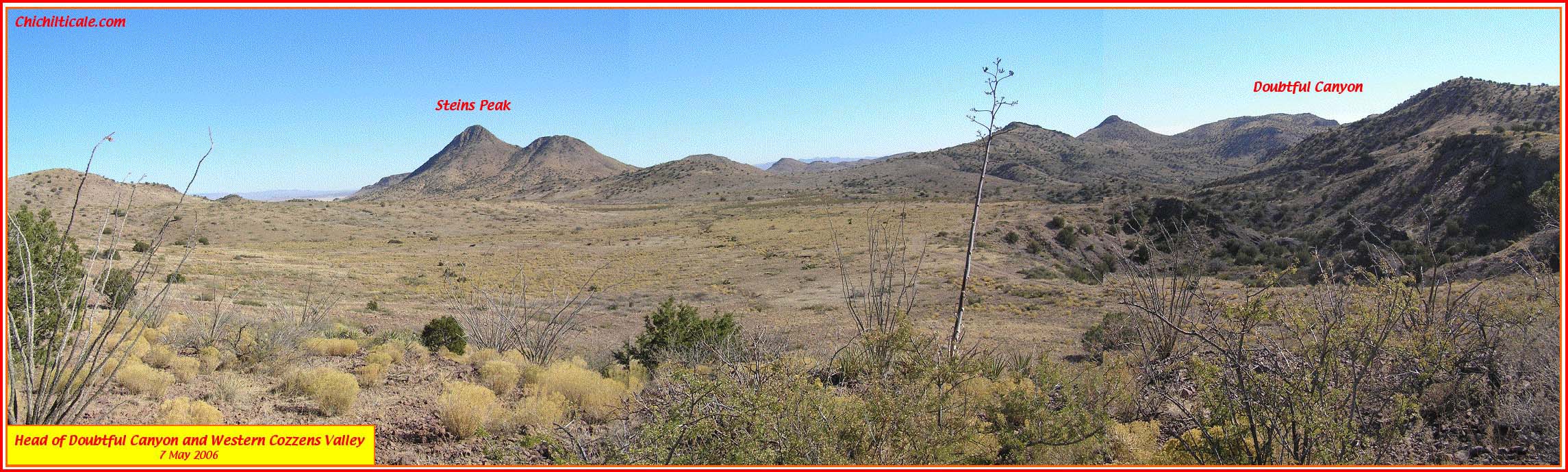

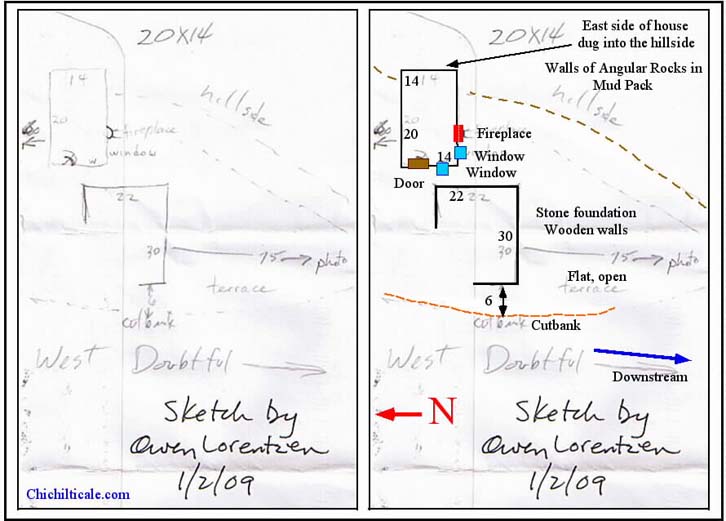

Three years later, in January 2009, four veterans of Kuykendall Ruins exploration conducted a Blennert sled search of a portion of the eastern end of the canyon on the Fred and Vera Braidfoot homestead, at a unique spot called Tsisl-Inoni-bi-yi-tu, which in the Apache language means "Rock-white-in-water." This locale is appropriately named because geological conditions there cause white, impervious rhyolite lava (ignimbrite) to outcrop in Doubtful Arroyo, creating surface bedrock and forcing water to spring, resulting in white rocks in spring water. I had recognized the site in 2005, when my field exploration had discovered a series of six widely spaced piles of white signal stones aligned to indicate an extinct trail from Lyall Pass on the north side of Doubtful Canyon to Doubtful Arroyo. This triumvirate of favorable geological conditions for water, signal stones marking a trail, and an Apache place name recognizing the waterhole, suggested an old, reliable and well-known fountain, one suitable for the Coronado Expedition and worthy of exploring for signs of the Captain General. (5)

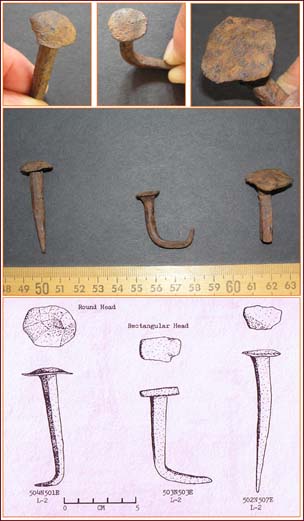

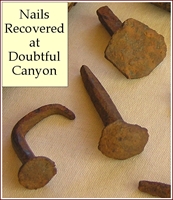

The team's January 2009 Blennert sledding at Rock-white-in-water resulted in the discovery of twelve lead shot, four of which were subsequently identified by isotope analysis as being composed of lead from a Spanish source location. Closely associated with three of these Spanish lead shot (Doubtful Canyon 3, 9, 10) the team found seven wrought iron nails. These were sent to the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, where collections specialist James B. Legg examined the pieces and reported their similarities in form, function and craftsmanship with sixteenth-century Santa Elena nails. The Doubtful Canyon nails also showed these similarities to nails found at Bayahá, a sixteenth-century settlement in modern Haiti. Figures are numbered upper left (1) to lower right (6). Figs. 1-5 illustrate comparisons between Doubtful Canyon and Santa Elena nails. Fig. 6 compares Doubtful Canyon and Bayahá nails.

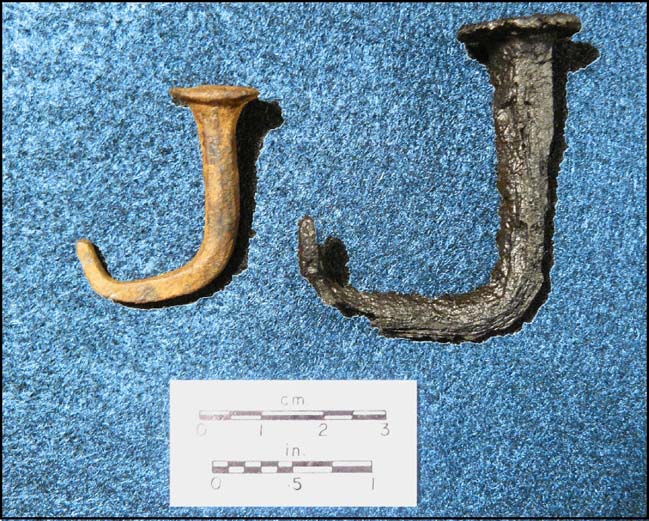

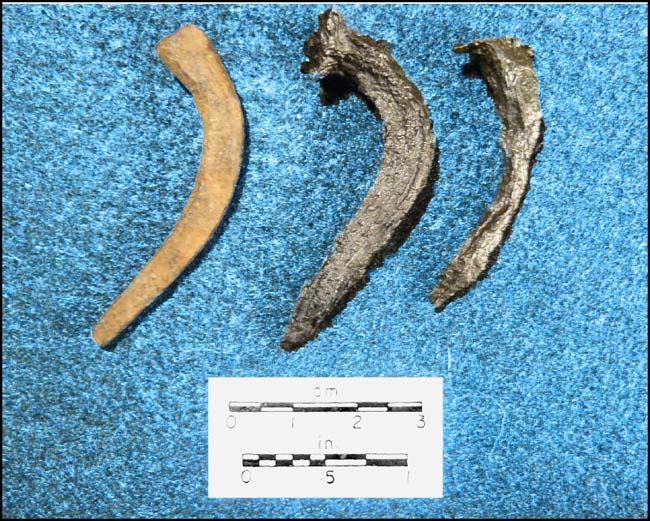

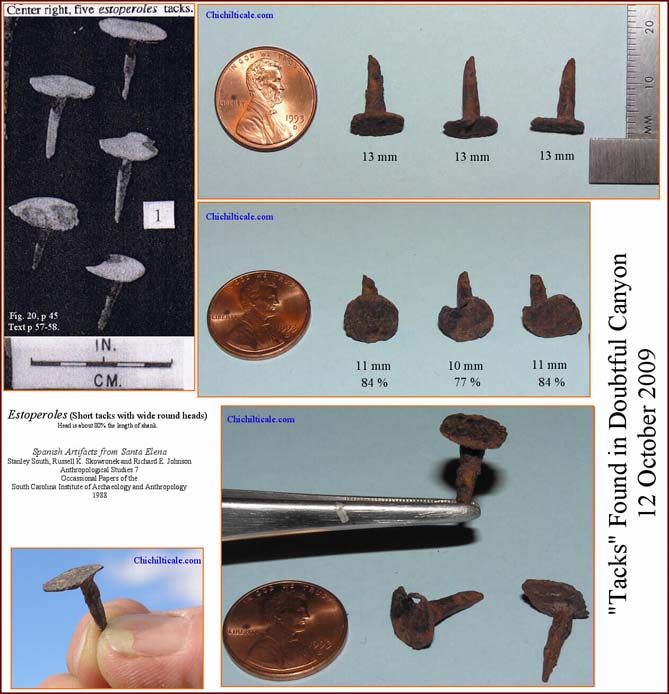

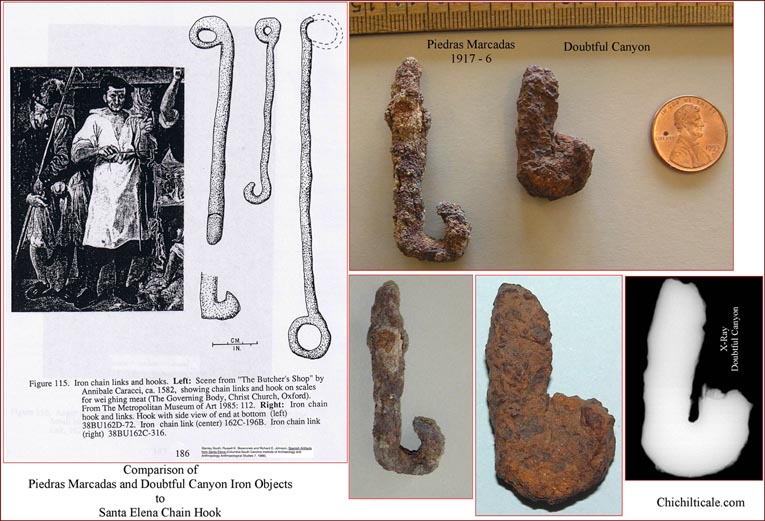

Additional exploration at Doubtful Canyon in September 2009 resulted in the discovery of three wide, round-headed, short-shanked tacks. Historian and nail expert Eugene Lyon identified these as estoperoles exhibiting the same charcteristics as those found at 1566-1587 Santa Elena on modern Parris Island in South Carolina. Fig. 7 compares tacks found at Doubtful Canyon to estoperoles excavated at Santa Elena. Also recovered from Doubtful Canyon was a chain hook similar in form, function, and craftsmanship to one found at the Coronado site of Piedras Marcadas. The totality of the Doubtful Canyon nails and tacks exhibiting characteristics comparable to such pieces found at Santa Elena and Bayahá, plus the chain hook similar to ones from Piedras Marcadas and Santa Elena, plus five lead shot being from a Spanish source location, plus the close proximity of three of the Spanish balls to the iron artifacts, offers compelling tangible evidence of the Coronado Expedition. (6)

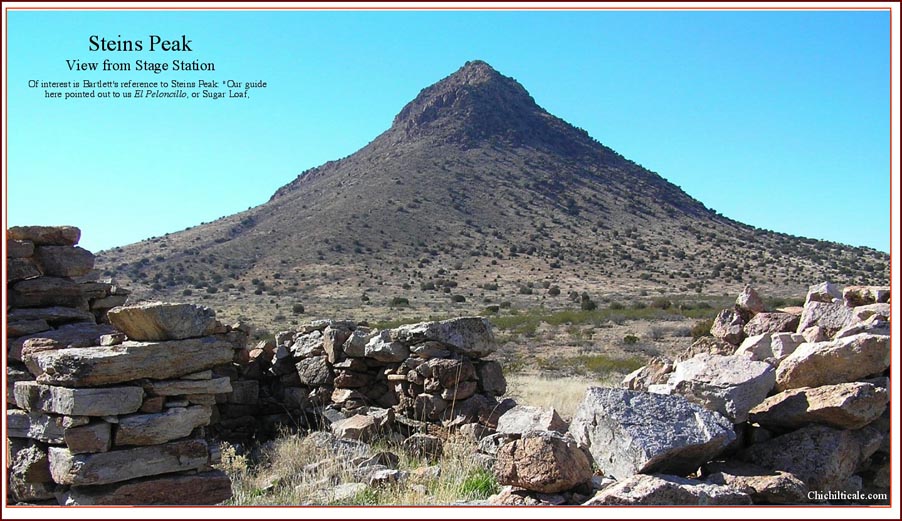

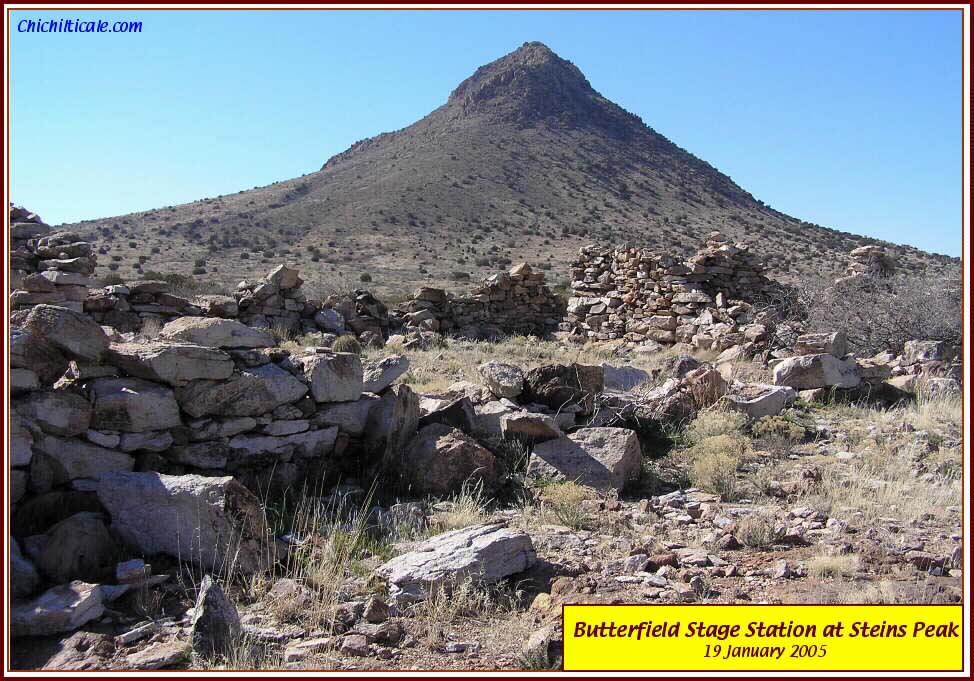

The minimum extent of the Coronado camp is suggested by the known artifact array being 1.87 miles (3 km.) in length stretched along Doubtful Arroyo, which has a total length of about five and a half miles (9 km). The Doubtful Arroyo water source is best described as a "laguna," a term used by ranchers in modern Sonora, Mexico, to signify intermittent pools of water in an otherwise dry arroyo. The word "charco" is often used in New Mexico for this geomorphology. A similar setting existed at Kuykendall Ruins. Campsites and grazing in Doubtful Canyon would have been located on level grassland east and west of Steins Peak. Trees providing fuelwood and shade grew in the arroyo. The attraction of the canyon as a place for livestock grazing along a major trail is attested by newspaper correspondent J. M. Farwell, who passed through Doubtful Canyon on the westbound Butterfield stage in late October 1858. He reported that at the stage station on the east flank of Steins Peak was "encamped a very large American train from the west" and that a mile east of the station were "25,000 sheep owned by a Mexican who is with them on their way to a California market." These sheep would have been grazing in the level grassland around the Tub and Doubtful Boulder, and would have been watering in Doubtful Arroyo. (7)

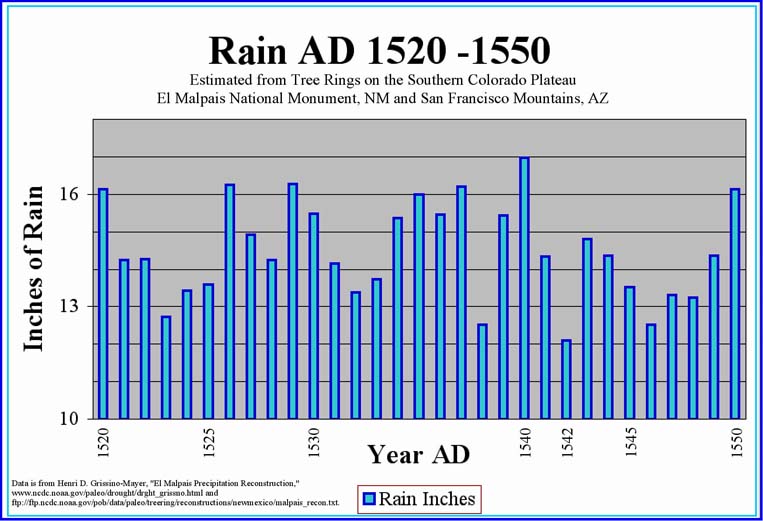

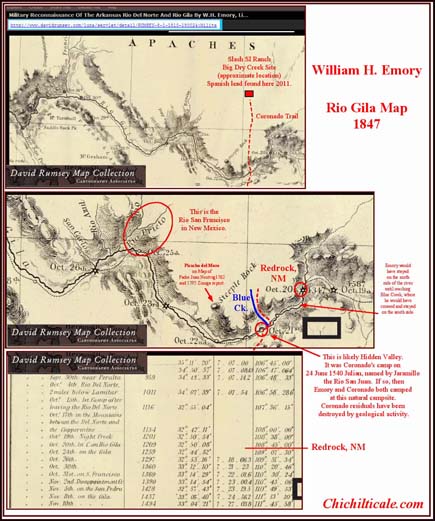

Applying the modern Gregorian calendar for purposes of comparing climate, Coronado's advance party was at Doubtful Canyon on 3 July 1540. Referencing the climate reconstruction proposed by dendrochronologist Henri D. Grissino-Mayer, 1540 was a wet year. The summer monsoon was likely underway and provided water to both the arroyo and to Cozzens Lake, creating a fairway of favorable camps beside grassland that was greening from the rains. (8) The following army passed through the canyon in early October. Given the wet year, Cozzens Lake probably held water, and the arroyo and springs were likely charged from the monsoon that would have normally lasted into September, but maybe extended into October, and the grassland would have been bountiful from the summer rains. The retreating army occupied the canyon in late April 1542, after the seasonal winter rains had ended in March. Being as the climate was cold during those years (the Río Grande froze), there might have been winter snow on the canyon mountains, and spring would have brought snowmelt to charge the water supply. Spring grazing would have been on dry grass grown the previous summer or from springtime green shoots. The presence of good grazing along an extended linear watercourse containing fuelwood and shade is a mutual attribute conjoining Kuykendall Ruins and Doubtful Canyon.

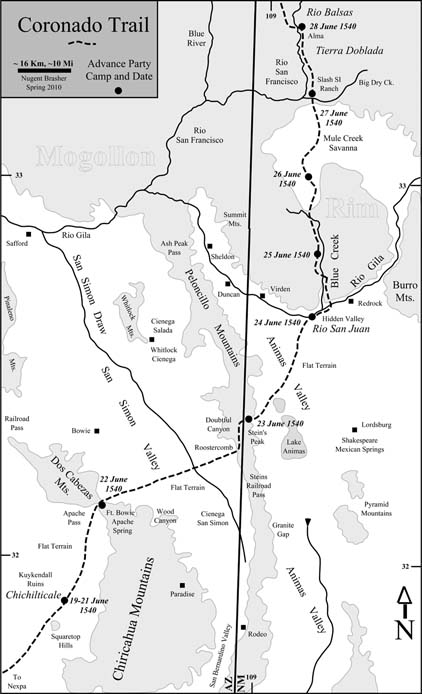

Given the presumed discovery of Chichilticale at Kuykendall Ruins, the location of Doubtful Canyon as a Coronado camp fits the temporal record of travel by the advance party as presented in Jaramillo's narrative. Moreover, the artifacts my team discovered at Doubtful Canyon offer tangible evidence of the Captain General in the canyon. The entirety of this evidence suggests that Coronado first entered modern New Mexico on the Julian calendar date of 23 June 1540, and that he did so along a prehistoric Indian trail that would some three hundred years later become part of the Butterfield Trail.

Isotope analysis strongly supports the conclusion that members of the Coronado Expedition carried shot that included balls made from Spanish lead sources. In addressing the issue of whether the Spanish lead found specifically at Doubtful Canyon arrived with Coronado or with later Spaniards, I reasoned that the Spanish developed their local mineral sources such that as the years progressed beyond 1521, less frequently did lead arrive in Mexico from Spain, eventually ceasing altogether.

Historians Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint provided evidence for my presumption. They pointed out "the collapse of the Spanish economy in the last half of the 1500s, from which the country did not fully recover for about 400 years. The combination of influx of American [New World] silver and [Spanish] military adventurism brought inflation followed by 'offshore out-sourcing' that nearly killed Spanish industry and mining on the peninsula and then caused three successive bankruptcies of the royal treasury." At the beginning of this economic failure there were active Spanish lead mines, but "when the economy collapsed, much mining in peninsular Spain simply stopped and didn’t [resume] again until the very late 1700s. In the 1600s and at least the first half of the 1700s, much of the lead used in Spain was coming from England. This increases the chance that lead balls from Spain at presumed Coronado route locations are from the 1500s and not later." (9)

Historian Clarence Henry Haring described Spanish maritime transport from Spain to the Middle New World as irregular at best, eventually trickling to almost nothing. By 1526, Spanish maritime transport was threatened by French corsairs. The Spanish responded to this in 1537 by sending a royal armada to the New World for the purpose of protecting the riches transported to Spain. Another armada sailed in the summer of 1542, the year the Coronado Expedition returned from Cíbola to Mexico City, and the ships did not go back to Spain until May 1543. The following August the Spaniards decreed that protected fleets should sail annually, and by 1550 the practice was in mode. Haring commented on its success: "Annual sailings were not the invariable rule, although they were the ideal striven after, and sometimes achieved. From about 1580 onward a year was frequently skipped, and toward the middle of the seventeenth-century, as the monarchy declined, the sailings became more and more irregular." Haring reported that "after 1651 Mexico was no longer able to support an annual flota; and that whereas formerly the fleets attained to a size of eight or nine thousand tons… if one of three thousand could be dispatched every two years, it was considered a miracle." This description supports the presumption of continuously fewer opportunities for Spanish lead to arrive in the Middle New World after the time of Coronado.

In 1522, Spanish ships were required by ordinance to carry arms and ammunition. Haring wrote, "For each large gun there were to be supplied three dozen shot, and for each of the pasavolantes (cannons) six dozen, with molds and lead to make bullets for the espingardas (small Moorish cannons). There were likewise two hundredweight of powder, ten crossbows with eight dozen arrows… None of this equipment might be sold or left [in the Middle New World]." The ordinance of 13 February 1552 required vessels, depending upon their tonnage, to carry twelve, twenty, or thirty arquebuses and crossbows. Twenty to fifty lead balls were required for the each gun. Haring reported that "molds for making lead bullets" were mandatory. The requirement of both lead shot and molds suggests that unfashioned lead was also likely carried on the ships. The Statement of Provisions for the Armada of Pedro de las Roelas, 1563 – 64, lists "two hundredweights of lead for shot for the arquebuses," thereby providing evidence of crude lead aboard Spanish ships. This reporting supports the possibility of Spanish lead arrivng in the Middle New World until at least the middle 1600s, although how much lead actually made it off the ships and into Mexico remains unknown.

Spain was not inclined to export lead. Despite the economic collapse of the latter sixteenth-century, Spanish demand for lead increased, constraining Spain's capacity to export lead to the New World. Spanish mining historian Francisco Gutiérrez Guzmán reported a number of factors that increased lead demand and subsequent shortages. He reported that beginning in 1514 the hulls of ships, especially those crossing the Atlantic, were lined with lead for the first time. Exacerbating the lead demand, a building construction boom occurred in Spain during the middle sixteenth-century, and lead was heavily used in the manufacture of roofs and conduits for water supplies. However, Spanish lead production was so diminished that lead was purchased from Flandes (Flanders). In 1564 the fledgling Linares mining district produced such an insignificant amount of lead that it was not named as a center, rather was included in the Alcudia-Almodóvar district. Nonetheless, due to increasing demand for lead and the concomitant depletion of the Alcudia-Almodóvar lead mines, by December 1565 Linares had become the largest lead producer in Spain and remained so through the last quarter of that century. During that time, especially from 1572 through 1579, demand for lead by military and maritime interests increased. In 1578 the demand for lead from Linares was so great that the Spanish crown consumed all the production, as it did between 1593 and 1598. By the seventeenth-century conditions had so deteriorated that the Spaniards were forced to buy ships from Holland, copper from Germany, and tin and lead from England, casting Spain into the dubious posture of being totally dependent on foreign manufacturing. These shortages continued into 1752 when lead production had declined to the extent that only one of thirty lead mines remained active in Linares. In 1778 the general administrator of maritime mail in Habana requested from Spain lead plates for preservation of mail ships. The request was denied because there was no more lead of such dimensions in the government stockpile. Under conditions of restrained domestic supply and hindered maritime transportation, it seems likely that little, if any, lead was exported by Spain to Mexico after the middle sixteenth-century. (10)

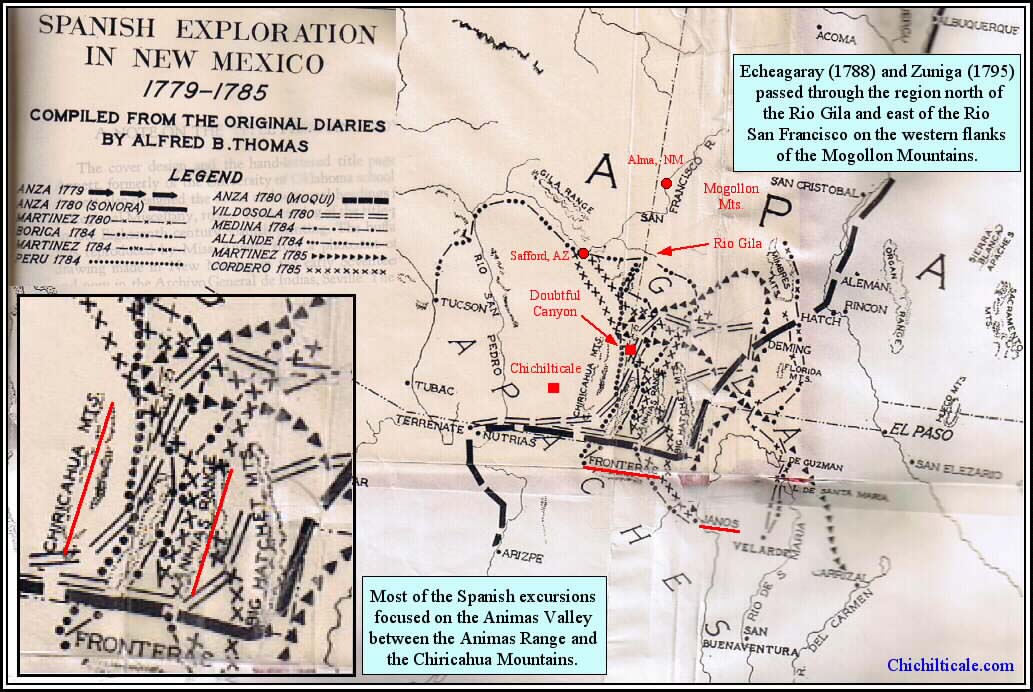

For purposes of dating artifacts found at Doubtful Canyon, I found it essential to consider the history of that canyon. In a previous report I described the region including Doubtful Canyon as being seldom visited by Spaniards, with the first Spaniards after Coronado not appearing until the 1690s, and this in an area far southwest of the canyon. (11) Beginning in the early 1780s a number of excursions occurred in the Doubtful Canyon region; historian Alfred B. Thomas reported some of these.

Following independence from Spain in 1821 and extending to 1851, the Mexican military occasionally visited the Doubtful Canyon region. American mountain man David Jackson led a party of eleven men from Santa Fe to California in 1831. “Each man had a riding mule; there were seven pack mules [and] five of the pack mules were loaded with Mexican silver dollars… Their route proceeded from water hole to water hole by way of Doubtful Canyon, Apache Pass, [Sulphur Springs Valley] and Dragoon Wash to the San Pedro River just north of present St. David, Arizona… This direct route had been traversed in sections over its complete length by various Spanish and Mexican military parties… [until 1851] on account of Indian hostilities." (13) Mexican military articles dating 1821 to 1851 could be present in Doubtful Canyon.

After Jackson opened the Doubtful Canyon route there is no record of its having been used again by emigrants. During the rush to California in 1849, the Gila Trail was the preferred route, a portion of which led southwest from the south end of the Burro Mountains to the San Bernardino Ranch, and then turned west toward Santa Cruz. The Fremont Association was the first recorded party to break from that traditional route. I interpreted the westward path of the Fremont emigrants to include a close proximity to Soldier’s Farewell Mountain, to the water pools on the northeastern side of the Pyramid Mountains near modern Lordsburg, to a dry camp on the western side of South Pyramid Peak, to a crossing of the Peloncillo Mountains near Granite Gap, to the Cienega San Simón (El Sauz), to a San Simón Valley dry camp in the San Simón - Wood Mountain area, to a watered camp in the Wood Canyon area, and to Apache Spring. (See Map 2.) My reading of the record did not favor a passage through Doubtful Canyon. If I am correct in my interpretation of the route, and if emigrants following the Fremont Association traced the same route, then Doubtful Canyon hosted few wagoneer gold rush travelers, suggesting that artifacts of that emigration event should not be expected in the canyon. (14)

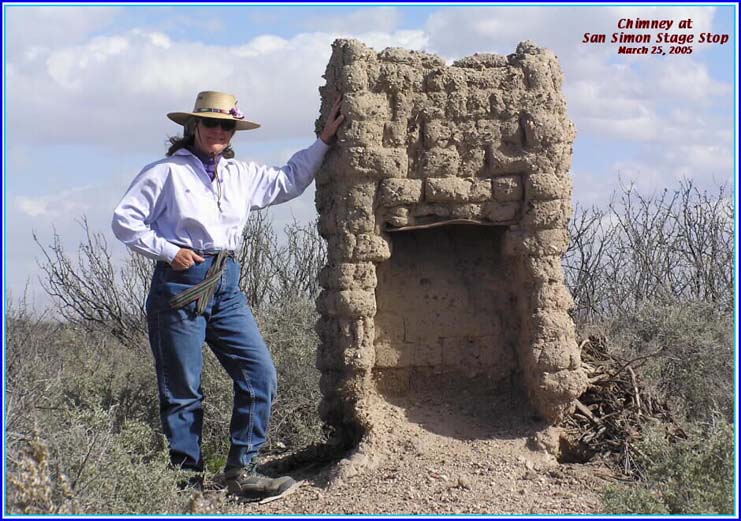

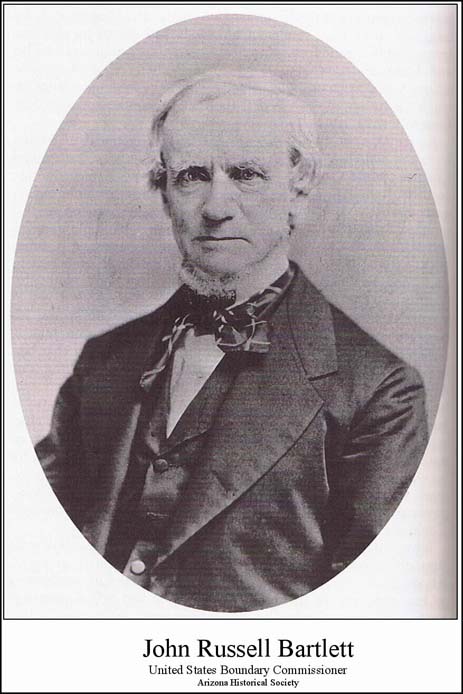

Following the Mexican-American War, the treaty-makers at Guadalupe Hidalgo, on 2 February 1848, established the boundary between the United States and Mexico. The effort to effectuate this boundary brought United States Land Commissioner John Russell Bartlett to the Southwest, and he produced an illustrated account of his travels. Using this account, I interpreted Bartlett to have been camped at the foot of Sugar Loaf Hill (Steins Peak) in Doubtful Canyon the morning of 1 September 1851. On 2 September, Bartlett split his party into two groups, deliberately sending the wagons through modern Steins railroad pass while he and the pack mules followed Doubtful Canyon to its western side at the Roostercomb. (15)

Bartlett did not bring a wagon through Doubtful Canyon in 1851. Nor had Jackson in 1831. Possibly their wagons could not maneuver the terrain. One of the first to traverse the canyon in a wagon was the San Antonio and San Diego Mail Company (SA&SD) in 1857. The Overland Mail Company (Butterfield) began operation a year later. Both these lines had stations in Doubtful Canyon. The Butterfield station was a meal stop, so a cook plus a station master were the minimum staff, but the station probably also included a farrier-wagoner-harness cowboy. The presence of the station represented an occupation in the canyon and these dates provide a benchmark for the beginning of an increased American presence in Doubtful Canyon. (16) Wagons and coaches frequented Doubtful Canyon until the summer of 1861, when the SA&SD ceased operations after the Butterfield had done so the previous March. (17) The stagecoaches and freight wagons returned to the region in 1867, when the National Mail and Transportation Company established a station at Mexican Springs (Shakespeare), operating until 1881. (18) This history suggests that metal artifacts representing eighteen discontinuous years of stagecoach and freight wagon traffic should be expected in the canyon.

An increasing American military presence began in Doubtful Canyon in 1861. The Bascom Affair of that year initiated war with the Apaches. Fort Bowie was built in 1862. Various companies of the Union California Volunteers 5th Regiment were stationed at Fort Bowie and Fort Cummings during the span from February 1862 to December 1864. In 1871 President Ulysses Simpson Grant sent a peace commission to Arizona Territory with orders to establish Indian reservations. Within a year, five reservations had been designated. Not all Apaches elected to go to a reservation. The United States military was engaged in war with the Apaches by 1877. The conflict lasted until a peace treaty in 1886. Fort Bowie was abandoned in 1894. (19) Throughout the thirty-three years of Apache – American conflict, the United States military infrequently, but periodically, visited Doubtful Canyon, finally ending their patrols by 1894. Metal military objects from this period of presence should be expected in a representative sampling of discovered artifacts.

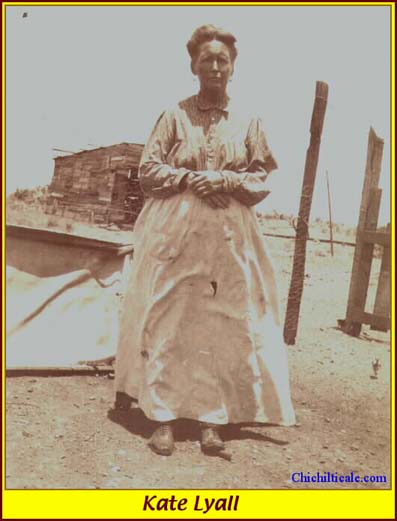

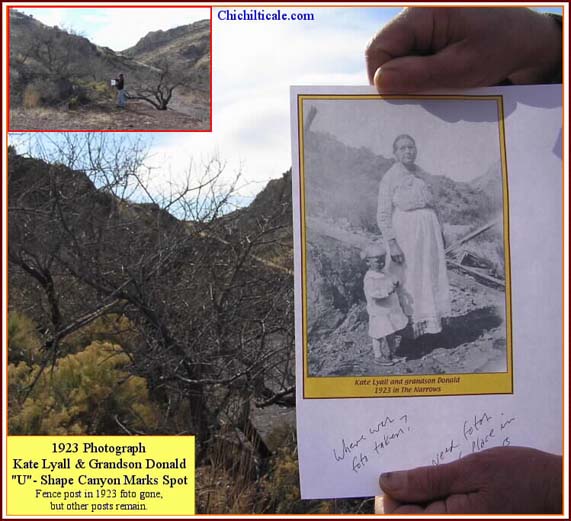

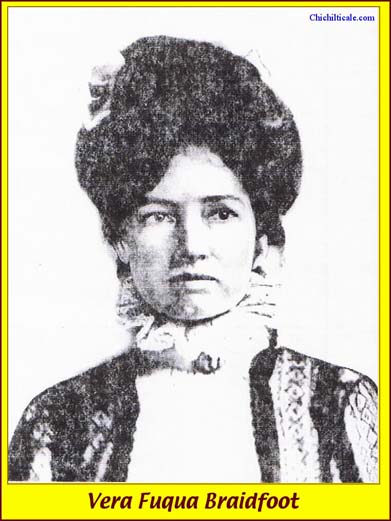

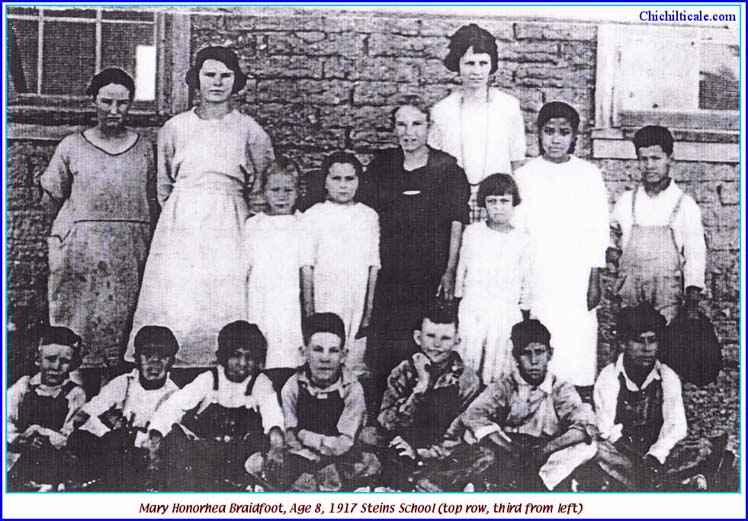

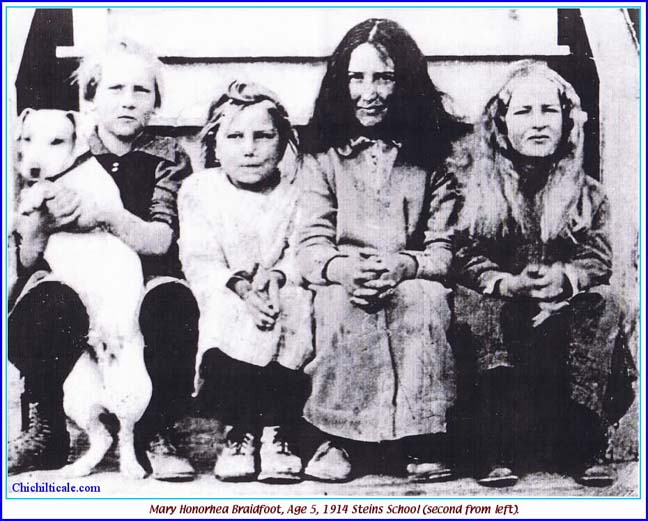

Mr. Gould was the first Anglo-American resident of Doubtful Canyon, arriving before 1902. He created a dugout in the side of the canyon in the Narrows at a spot of permanent surface water. As early as 1902, and before 1910, Margaret Catheryn Eshom Lyall, at that time in her fifties and known as Kate, bought the Gould dugout and moved into Doubtful Canyon. Her homestead was patented on 24 June 1924. Elmer Archer Lyall, known as Arch, joined his mother Kate in 1912 and patented his Little Doubtful homestead in May 1924. By 1914 Fred and Vera Fuqua Braidfoot had arrived in the canyon; they patented their land in 1919. Arch Lyall moved to San Simón in 1922, leaving his Little Doubtful ranch unoccupied. Kate Lyall remained in Doubtful Canyon until May of 1928. No Lyall ever lived in the canyon after Kate left – only the Braidfoot family remained. Mary Honorhea Braidfoot, daughter of Fred and Vera, patented a homestead west of her parents in 1937, the same year her father Fred died. Widow Vera lived until 1953. Four years later Honorhea, the only surviving Braidfoot, died, causing both Braidfoot homesteads to be abandoned, leaving Doubtful Canyon empty of human occupation. (20) The homesteader period lasted from about 1900 to 1957 and included three home sites. Artifacts from that time period should be expected in the canyon.

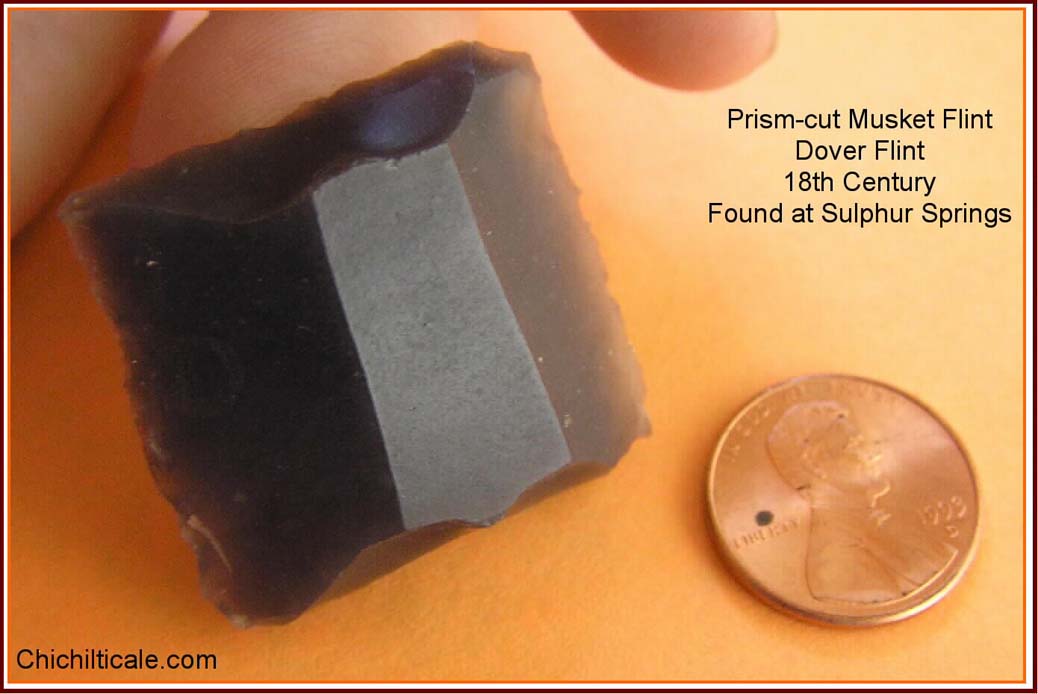

Historical artifacts expected in Doubtful Canyon lend themselves well to temporal categorization. Given that artifacts discovered in Doubtful Canyon were not transported there by secondary bearers, the following assessment seems reasonable. If Coronado were truly present with his hundreds of metal bearers, there should be an expectation of finding 1540 -1542 domestic and military artifacts. My team found seven nails and three tacks that are representative in form, function and craftsmanship of this period, as well as five shot composed of Spanish lead and interpreted to be sixteenth-century in age. Few Spanish pieces dating between 1542 and 1780 should be expected because the Spanish presence was slight, maybe even absent. Spanish military pieces dating between 1780 and 1821 could be present, but should not be expected because Spanish presence was minor, considerably less than the number of metal bearers in the various Coronado parties. Likewise, Mexican military pieces dating 1821 to 1849 could be present, but since Mexican presence was slight, such artifacts should not be anticipated. Supporting this contention, my team found no iron objects that could conclusively be identified with the post-Coronado Spanish or Mexican periods, and, most notably, isotope analysis found no conclusive Mexican lead among the thirteen shot found in the canyon, lending support to the scarcity of post-Coronado Spanish or Mexican visitors. American passenger and freight artifacts dating 1857 to 1894 should be anticipated. American military artifacts should be expected to range in dates from 1861 to 1894. My team found American military and civilian personal items dating from 1850 to the 20th century, as well as wagon bolts, barrel straps, horse and mule shoes, and cut and wire nails. Homesteader artifacts should date from shortly before 1902 until 1957, and, as expected, the area is littered with samples from that period.

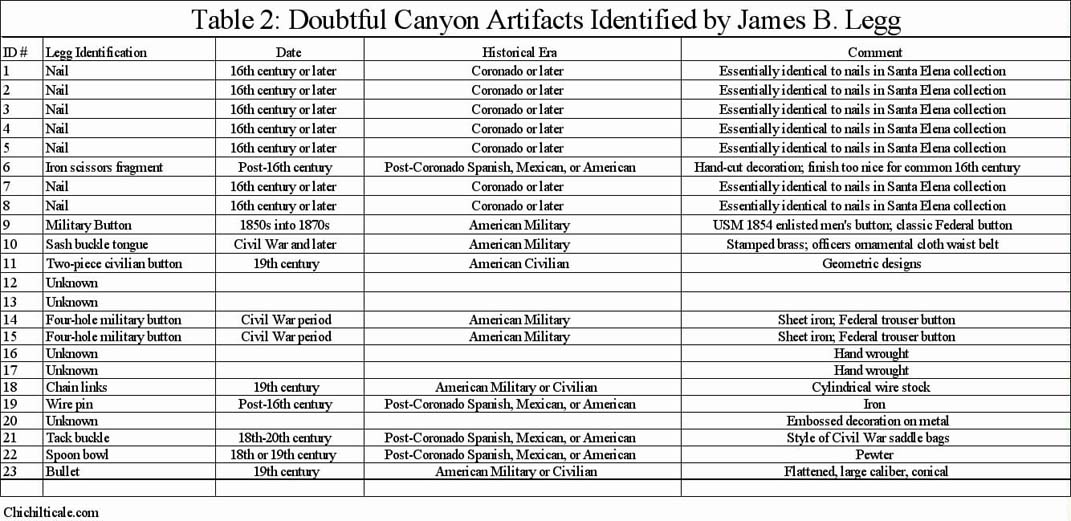

Table 2 was generated from the February 2009 report provided by Legg. (21) The table shows a positive correlation between artifact and historical period as predicted by interpreting the written history. Additional evidence of nineteenth-century American military or civilian artifacts are seven lead shot ranging from 0.31 caliber to 0.51 caliber identified by isotope ratios as composed of midwestern USA lead.

Of consequence to artifact dating, the historical calendar suggests that any domestic Spanish artifact, if it can be shown to have been available in the sixteenth-century, cannot be excluded as possibly being from the Coronado Expedition inventory. In favor of Spanish artifacts found in Doubtful Canyon being of a Coronado origin is that the variety and number of metal bearers with Coronado, if he passed through the canyon at all, far exceeded the total of all subsequent Spanish bearers, reinforcing the suggestion that any Doubtful Canyon Spanish artifact, especially if it is domestic in nature, is more likely than not a residual of the expedition. This association becomes even more probable as the number of domestic items increases. The evidence of Spanish lead, when added to the history of the canyon and to the presence of the compelling nails and tacks, significantly strengthens the likelihood of these being vestiges of the sixteenth-century adventure and the concomitant likelihood that Doubtful Canyon was a campsite along the Coronado Trail.

Isotope analysis identified two shot of Spanish lead and two of midwestern USA lead at Kuykendall Ruins. In a previous report I presented history indicating that the first Spaniards returning to the Chichilticale region after Coronado did not arrive until about 1690, some 150 years after the expedition, and some 170 years after the Spaniards conquered Mexico City. (22) This hiatus in Spanish presence coupled with evidence of a diminishing or terminated supply of lead from Spain serves to strengthen the likelihood that the shot of Spanish lead found at Kuykendall Ruins originated with some of the hundreds of 1540 – 1542 Coronado expeditionaries rather than with one of the few travelers arriving after 1690. This reasoning reinforces the association of Kuykendall Ruins with Chichilticale.

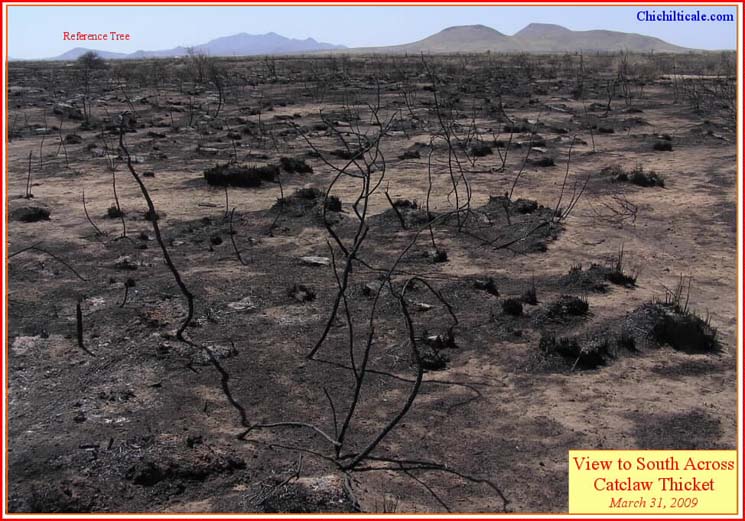

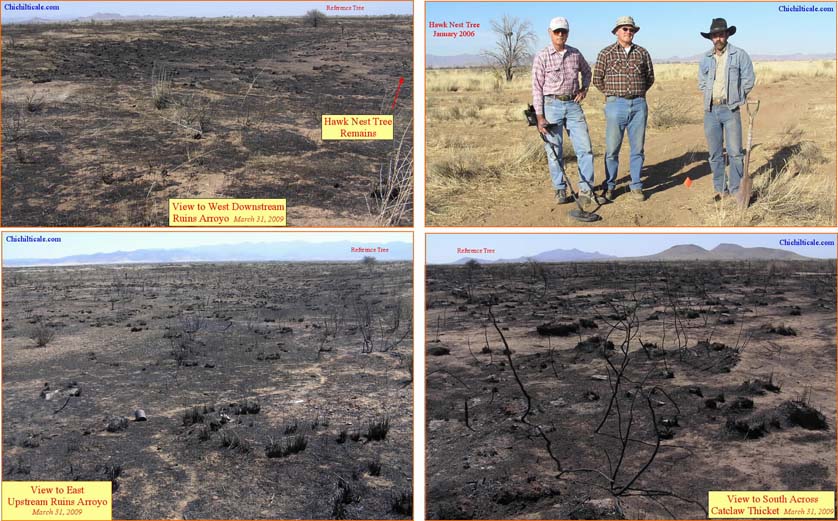

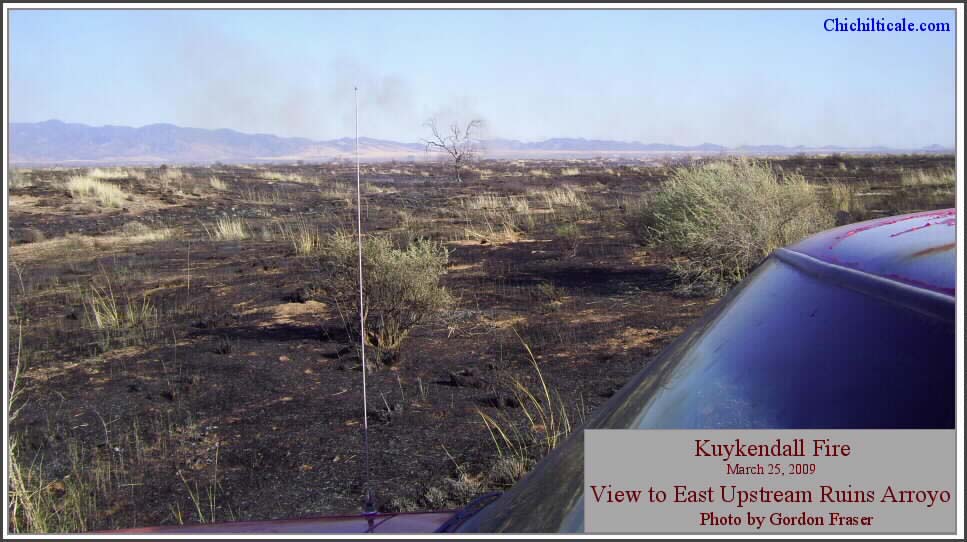

Metal detecting at Kuykendall Ruins continued in 2009. On 25 March, the Geronimo range fire burned 2600 acres in Cochise County, Arizona, including the sites of Kuykendall Ruins and FF:2:6. (23) Six days later two team members and I conducted field reconnaissance and observed that areas previously occupied by tall sacaton and catclaw had been almost totally cleared by the blaze. Strong spring winds during the following several weeks swept the exposed surface clean, creating a unique opportunity to pull our Blennert sleds across terrain previously inaccessible due to obstructive vegetation. Eight team members from three states converged on Kuykendall Ruins on 19 April and conducted a three-day search of conscientiously selected locations in Ruins Arroyo, Ruins Plain, and Clearings Arroyo. The team employed two Blennert sleds in the gridded search areas, and utilized handheld metal detectors where burned catclaw stumps prevented sledding.

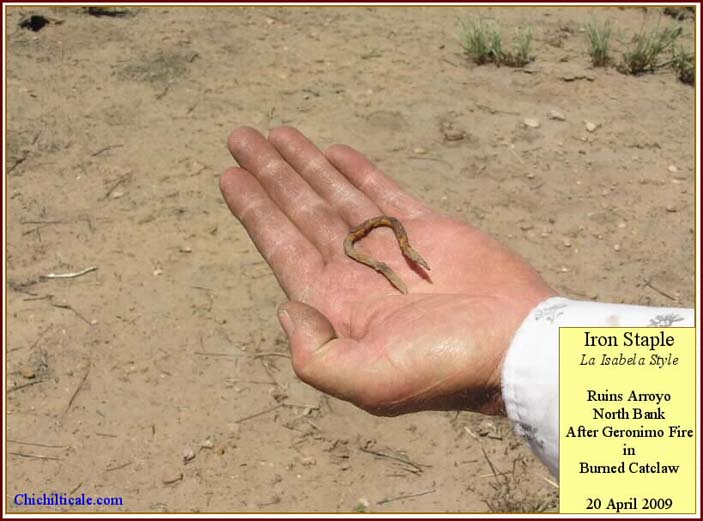

On the north bank of Ruins Arroyo in a burned catclaw thicket, team member Loro Lorentzen discovered an iron staple of the La Isabela style. Two iron staples of this fashion had been previously discovered and reported. (24) Fig. 8 shows three La Isabela style iron staples found at Kuykendall Ruins.

Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) is sometimes effective in determination of the most recent date that a rock reached a temperature sufficient to reset it from geological time. I wrote that OSL dating "should be conducted on a significant number of thermal features (piles of burned rocks) suspected to be Coronado campfires. The number of dates obtained must be sufficient to provide a statistically relevant conclusion." (25) To evaluate the feasibility of expensive OSL dating of a statistically meaningful number of suspected campfires at Kuykendall Ruins, I submitted for OSL test dating two burned rock fragments to Dr. Jean-Luc Schwenninger at the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art (RLAHA) at the University of Oxford. The fragment taken from a buried fire near where the iron bolthead was found (bolthead fire) dated 330 plus/minus 35 years before 2007, or 1642-1712. The fragment from a surface fire near where several irons hooklets were found (hooklet fire) tested as ">9000: insufficient heating." This means that the hooklet fire rock had not reached a temperature sufficient to reset the geological date. Being as I have suggested that many of the thermal features are "fires of only a brief duration" because they were Coronado Expedition fires, the OSL result for the hooklet fire is cautiously supportive. The bolthead point fire cannot be excluded as a Coronado fire because post-Coronado visitors may have reheated the rocks. (26) The ambiguous results of these two tests have caused us to hold in abeyance any further OSL dating efforts.

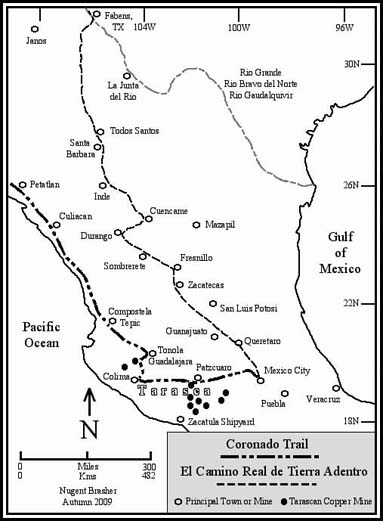

Lead isotope analysis concluded that Spanish and Middle New World lead were used to make shot found at both Hawikku and at Piedras Marcadas in Tiguex, and that midwestern USA lead was found in a ball from Kyakima. The post-Coronado history of what is now modern New Mexico is relevant to determination of the most likely bearers for the balls of Spanish lead. In 1546 a bonanza of mineral wealth was discovered at Zacatecas. Historian John Francis Bannon described the event as "…North America had its first boom town. Other [mining discoveries] followed in quick succession – some along the eastern face of the Sierra Madre, such as Guanajuato [in 1559] and Aguas Calientes [in 1575], and farther to the east on a line northward from Querétaro, such as San Luis Potosí [in 1592] and Mazapil [in 1569]… A new province, Nueva Vizcaya, was established in the early 1560s [with Durango as its capital]… From Durango the Spaniards pushed… into [modern] Chihuahua… to Santa Bárbara, [founded in 1567 and located fifteen kilometers southwest of modern Hidalgo del Parral]. This last outpost, on the headwaters of one of the tributaries of the Río Conchos [and where silver had been discovered in 1567], was the center from which several expeditions to the farther north pushed out in the 1580s, expeditions which set the stage for the occupation of New Mexico…" (27) Historians George P. Hammond and Agapito Rey described Santa Bárbara as "the most renowned spot on the northern prong of Spanish advance in Mexico. It was the magnet that attracted a swarm of frontiersmen… [It was] the end of the line… and the home base for fitting out new prospecting ventures." (28) Fittingly, Santa Bárbara was the northern terminus of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. (See Map 3)

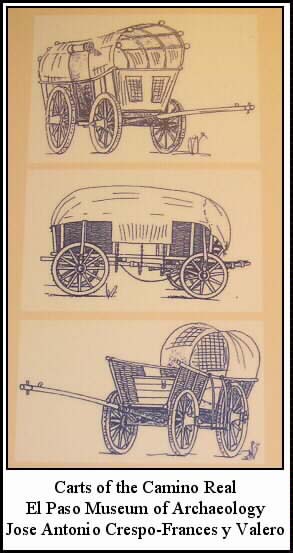

Any Spaniard known to have arrived at Hawikku or Tiguex after Coronado did so after the 1546 silver discovery at Zacatecas. These northbound Spaniards would have followed El Camino Real, the supply line road of the central corridor of Mexico that connected the rich mines between Querétaro and Santa Bárbara in newly founded Nueva Vizcaya. Construction of El Camino de La Plata, the stretch of El Camino Real between Querétaro on the south and Zacatecas on the north, began in 1550, and by 1552 was used by carts and wagons. In 1582 a traveler described the road as "through the mines of Zacatecas." Lead was a valuable byproduct of mining along El Camino de La Plata. (29)

Capt. Gen. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado did not travel El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. (See Map 3.) The 1540 – 1542 expedition departed Mexico City to the west toward Compostela (modern Tepic, Nayarit). Castañeda describes the route in his report of viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza traveling to that spot: "[The viceroy] departed for Compostela accompanied by many caballeros and noblemen, and he had New Year's Day of 1540 in Pasquaro (Pátzcuaro)… [and from there] he crossed all the land of Nueva España to Compostela." Being as the route to Compostela passed through northern Tarasca, it is almost certain that the road followed by the Spaniards was a pre-conquest Tarascan trail connecting trade, administrative centers and copper mines. From Pátzcuaro the route continued west to Colima. There the trail turned north to pass through another region of Tarascan copper mines, the farthest northwestern outposts in Tarasca, before reaching Compostela. Between Compostela and San Miguel de Culiacán, the northwestern outpost of New Spain, the trail hugged the coast, passing west of the future mines in Sinaloa. Map 3 shows that members of the Coronado Expedition were likely exposed to an opportunity to acquire lead from a Tarascan source (modern states of Jalisco and Michoacán). (30)

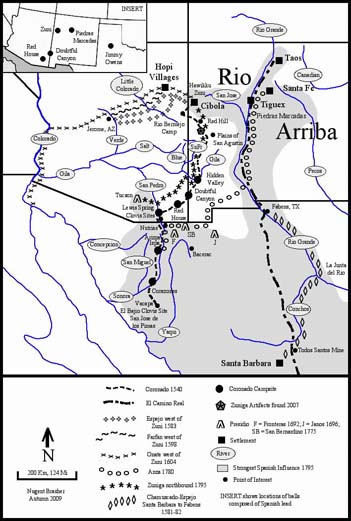

Post-Coronado travelers departing northbound from Santa Bárbara before 1598 would have followed a trail blazed for the purpose of hunting slaves to work in the mines near town. (See Map 4.) Early 1580s northbound explorers Captain Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado and Antonio de Espejo departed for modern New Mexico along that slave trail – first downstream along the Río Conchos in Mexico to its junction with the Río Guadalquivir (Río Grande), then upstream by that river to the pueblos in the upper valley, the region of Río Arriba, then west to Hawikku. Rejecting this traditional route, however, northbound colonist Juan de Oñate in 1598 followed another trail to Río Arriba. Historian Marc Simmons suspected that Oñate chose the alternate route because the Indians along the Río Conchos had grown hostile due to "slaving expeditions raiding their villages." Riley described the route: "[Oñate] struck out from a base in northern Chihuahua in a northwesterly direction, roughly following the line of modern Mexican Highway 15, but intercepting the Río Grande somewhat to the south and east of modern El Paso." Geographer Hal Jackson offered a reasoned selection of three places where Oñate could have crossed the Río del Norte (Río Grande) – all near Fabens, Texas. Oñate then followed the Río del Norte to Río Arriba. (31)

The Spaniards came back to New Mexico in 1581, some forty years after Coronado had departed in 1542. A hopeful group of thirty-one Spaniards led by Captain Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado and Franciscan Augustín Rodríquez departed on 5 June 1581 from Santa Bárbara, driving six hundred head of stock and ninety horses while transporting trade goods. The party reached Tiguex about the first of September, where they were not confronted by the Tiwas despite the savaging of the pueblos inflicted by Coronado some forty years previous. Chamuscado did not linger in Tiguex, instead continuing north and then east to the buffalo country of eastern New Mexico before returning to Tiguex in Río Arriba. At the beginning of this eastward trip, around 10 September, friar Juan de Santa María attempted to return to New Spain, but was killed by Indians after only two or three travel days to the south. After returning to Tiwa country the party explored to the west, appearing in Zuni on 15 December. (32) How long the group stayed at Zuni is unreported, but is likely measured in days rather than weeks. Chamuscado returned to Tiguex and then proceeded to the southeast to observe some reported salt deposits, after which he again returned to Tiwa country. As with his sojourn in Zuni, the total duration of Chamuscado's time in Tiguex was not lengthy, almost certainly less than two weeks. On 31 January 1582 Chamuscado departed Río Arriba without the two remaining friars. He had become ill and was being bled by his companions, and he died on the trail. On Easter Sunday, 15 April 1582, the small party reached Santa Bárbara. Immediately, Hernán Gallegos, an expedition member, rushed to Mexico City with news of the adventure. Included in his report was that "the land is flat and can be traveled on foot or on horseback with pack animals, and it is suitable for wagons." (33)

Franciscan authorities in Mexico City expressed alarm upon learning that one friar had been killed and the other two friars had not returned with Chamuscado, electing instead to remain in Río Arriba at Tiguex. In response, Fray Bernardino Beltrán organized a rescue party and wealthy Antonio de Espejo financed and directed it. On 10 November 1582, a group of about forty travelers, including some twelve to fourteen soldiers, the wife and three small children of one of the soldiers, the friar Beltrán, and the "captain" Espejo, departed Santa Bárbara via the Río Conchos route. The livestock included one hundred fifteen horses and mules, plus arms and munitions. Before reaching Tiguex in middle February 1583, Espejo had already learned that the two friars had been killed. Espejo found Tiguex abandoned, likely the result of fear of retaliation by Espejo.

Despite objections by Beltrán, Espejo took the opportunity to range as far west as central Arizona for the purpose of mineral prospecting. Leaving the Río del Norte north of Tiguex near modern San Felipe at the end of February, the explorers turned west, passing through Zia Pueblo and Acoma before reaching Hawikku on 15 March 1583. About three weeks later, Espejo and nine soldiers departed Hawikku and continued west. Beltrán remained in Hawikku with most of the expedition. Espejo passed through the Hopi pueblos on his search for mines. At Aguato (Awátovi) on Tuesday, 30 April 1583, the Espejo group partitioned into two parties of five men – one party continued west to near modern Jerome, Arizona, where Espejo visited mines shown him by the Indians; the other party, including "friendly Indians," returned to Zuni. Espejo was back at Zuni on 17 May 1583, his return being over a different route because he wanted to take the opportunity to observe and appraise the land, a process that accomplished finding a more level route from Zuni to the mines.

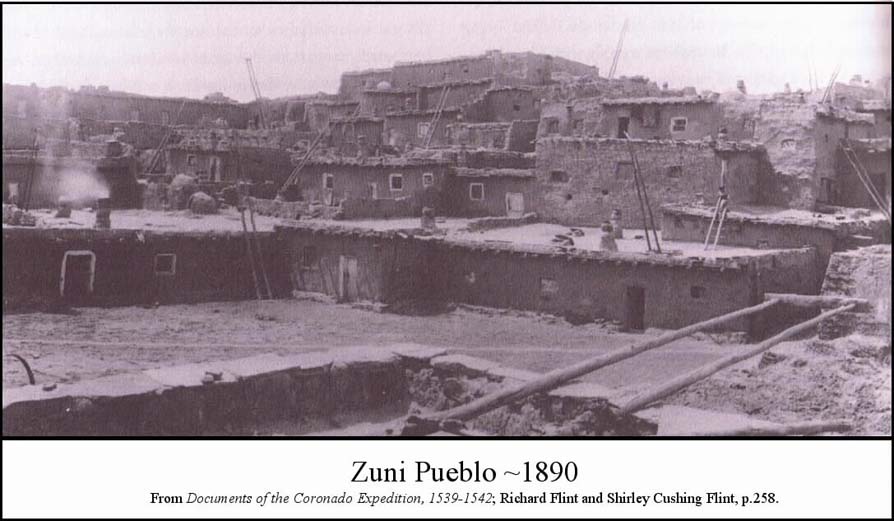

In Halona (modern Zuni), Espejo found that the five soldiers who had returned from Aguato "had not yet met the father or the other five companions." Nevertheless, Beltrán, with some three to five soldiers plus another two dozen people, were there, and they had been in Hawikku – Halona for two months, making their visit the longest by Spaniards since Coronado had withdrawn in 1542 with his 1,550-2,350 people and approximately 6,220 livestock.

Nine days after Espejo arrived in Halona, Beltrán resolved to return to the "land of peace" despite objections by Espejo, and shortly after 26 May the friar and about thirty followers headed toward Santa Bárbara. A few days later, on 31 May 1583 Espejo with eight fighting men and some servants left Zuni. Espejo likely retraced his route to Acoma, and near there the Spaniards skirmished with Querecho Indians residing in that vicinity. Continuing on, the party reached Tiguex on 19 June 1583. The trail between Acoma and the Río del Norte near Puala pueblo (Puaray) was new to Espejo because he had not followed that route on his journey to Zuni. As for Beltrán, historians Hammond and Rey reported that he and his followers "reached Santa Bárbara, safe and sound, before Espejo's group, but we have no record of their journey." Espejo was at Tiguex only a few days, during which he burned the Puala pueblo before heading east to Pecos, where he then turned south on 5 July 1583, forging a new trail via the Río Pecos on his way to the Río Conchos, reaching Santa Bárbara on 10 September 1583. (34) The sum total of Espejo's time in Tiwa country was about two weeks.

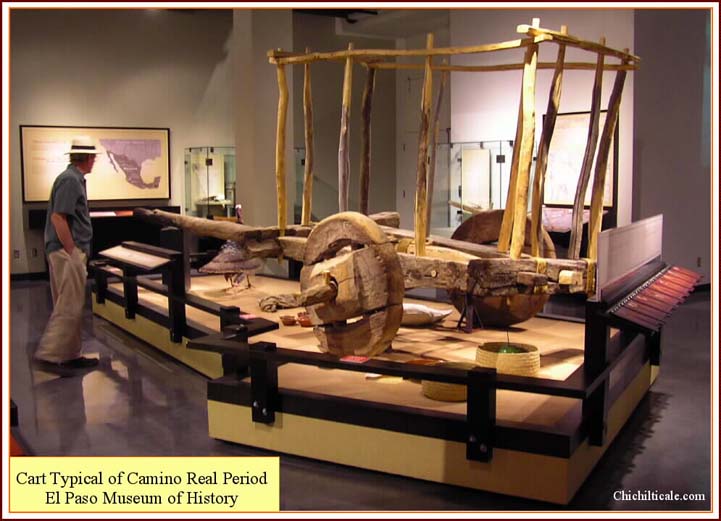

The expedition of Gaspar Castaño de Sosa departed modern Monclova, Coahuila, Mexico on 27 July 1590 accompanied by more than 160 men, women and children and their livestock, which included more than 250 oxen, in a convoy of at least ten carts bound for Río Arriba with the intent to colonize there. Castaño had sought permission from the viceroy for his expedition, but he had been denied; nevertheless he proceeded defiantly with his plan. About 10 March 1591, by way of west Texas, eastern New Mexico and Pecos pueblo, the party reached modern Santo Domingo, New Mexico, the first to do so employing wheeled carts, where they established a center of operations.

With twenty men, possibly on 12 March, Castaño rode south in search of mineral deposits. He reached the Río Grande near modern Bernalillo on about 13 or 14 March. He crossed the river for a brief visit before returning to the east side and turning south. On 14 or 15 March, Castaño ordered thirteen of his men to return to Santo Domingo. During the next two days the eight remaining Spaniards visited pueblos on both sides of the river in the vicinities of modern Alameda and Corrales. One night was passed on the west side of the river, possibly at or near Piedras Marcadas. On 15 or 16 March, Castaño began his return along the east side of the Río Grande to Santo Domingo, where his unauthorized adventure crumbled when Captain Juan Morlete arrived with fifty men to arrest Castaño and his men. The viceroy had ordered Morlete to impound all the expedition's goods and to bring them to Mexico City, and the record suggests that this was achieved. The total elapsed time of Castaño's presence in Tiguex was less than a week. Castaño, of course, never reached Zuni. (35)

Following Castaño de Sosa by three years, the unauthorized party of Antonio Gutiérrez de Humaña and Francisco Leyva de Bonilla and an unknown number of followers settled in Río Arriba at San Ildefonso pueblo. During the one year of their presence, the Spaniards traveled amongst the pueblos. While it can be presumed that they likely visited Tiguex, there is no record of them visiting Zuni, although since the party was looking for mines, it is reasonable to consider that they may have traveled there. (36)

Spanish explorer Juan de Oñate and his New Mexico colonists departed the Río San Gerónimo near the Todos Santos mines on 26 January 1598. Anthropologist David Snow reported that although he was "able to arrive at a count of some 560 persons with Oñate – mostly men of course – official correspondence in several places estimate some 700 persons." With respect to the number of livestock composing the expedition, using the translations of the Spanish documents provided by historians George P. Hammond and Agapito Rey, I tallied 8,149 animals. Oñate's advance party reached Tiguex by 24 June 1598, and, finding the country mostly deserted, the colonists passed through to arrive at Santo Domingo on 30 June, where they established their first settlement. The carts and wagons arrived on 18 August, and that date marks the largest concentration of Europeans and their provisions to occupy Río Arriba since Coronado had departed in 1542, as well as marking the beginning of the flood of European articles into the region. (37)

Oñate first arrived in Zuni on All Saints Day 1598 on his expedition to discover the South Sea. He and his military party reached Hawikku on 3 November, remaining until the eighth. During that time Captain Marcos Farfán de los Godos traveled to Zuni Salt Lake. Afterwards the party continued west to the Hopi villages where Oñate was told of people to the south who painted their bodies with colors of the earth. Oñate sent Captain Farfán to investigate while Oñate returned to Hawikku about 23 November 1598. On 11 December Farfán reported to Oñate in Hawikku that he had found silver mines. The following day, due to the coming winter and concern for his party, Oñate abandoned his quest for the South Sea and departed Zuni for Río Arriba. All told, the Oñate party had frequented Zuni for a period of about three and a half weeks. Six years later, in October 1604, Oñate returned to Zuni on his second attempt to reach the South Sea. Accompanying Oñate were two friars, a military captain and thirty soldiers. The party found four of the six Zuni pueblos in ruin, but inhabited, with Hawikku being the principal pueblo. Oñate successfully reached the mouth of the Río Colorado where it enters the Sea of Cortés, hardly the Pacific Ocean, but nevertheless believed to be the South Sea. In April 1605 the party passed through Zuni on its return to Río Arriba. Oñate's total elapsed presence at Hawikku in 1598, 1604, and 1605 likely lasted less than five weeks. (38)

Colonization and conversion began when Oñate arrived at Río Arriba in 1598, but missionaries were not sent to Zuni until 1629. That year Fray Francisco de Porras and Fray Roque Figueredo founded a church at Hawikku. Four years later the Zunis killed two missionaries and some soldiers, forcing abandonment of the mission. By 1643 the Spaniards had returned and the Zunis helped rebuild at Hawikku. The mission at Hawikku lasted until 1670, when Apaches killed the missionary, resulting in the total abandonment forever of Hawikku. The mission at Halona existed until the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, when the missionary was killed. Not until 1699 was a new church built, once again bringing the Spaniards to Halona. The Hawikku mission was not recreated because the Zunis adopted a more compact settlement. After 1700, traffic both military and religious in nature, increased between Río Arriba and Zuni, although the pueblo remained far removed from Spanish, then Mexican, and finally Anglo influence. (39)

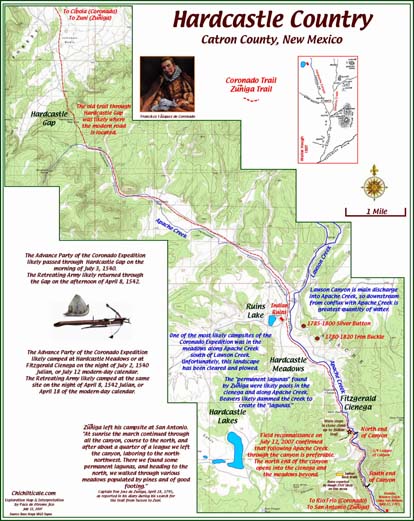

The first known post-Coronado Spaniard to arrive at Zuni from the southwest rather than the central corridor was Captain José de Zúñiga in 1795, who was exploring for a road connecting the Spanish colony at Tucson, Arizona, with Río Arriba. (40) (See Map 4) His was not the first effort to establish such a connection. In 1780 Governor Don Juan Bautista de Anza was credited with blazing a trail from Santa Fe to Arizpe (in modern Sonora, Mexico). The route was alongside the Río Grande southward to near modern Hatch, New Mexico, then southwest to the bootheel of New Mexico, then west to Las Nutrias, and finally south to Arizpe. The Anza route stayed south and east of the Coronado Trail that passed through modern southeastern Arizona and western New Mexico. (41) Seven years after the Anza adventure, Don Manuel de Echeagaray attempted to "open a route which would facilitate the exchange of goods [between Sonora and Santa Fe]." I have attempted to reconstruct the route of Echeagaray by studying the summary of his excursion offered by Hammond and Rey. My estimate is that the party reached the Plains of San Agustín near Horse Springs, New Mexico, before backtracking to Apache Creek and turning north to reach Hardcastle Gap before returning to the southwest. (42)

Seven years later, Zúñiga followed some of the Echeagaray route, eventually reaching Zuni, where he reported a missionary in the "Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Zuni" (Halona). Zúñiga also mentioned departing Halona to the southwest and camping at "an abandoned pueblo known as el agua caliente del Pueblo antiguo de Zuñi," likely Hawikku. Zúñiga did not proceed east of Zuni. (43)

The route taken by Zúñiga in 1795 may have been known long before. In 1760 Bishop Pedro Tamarón y Romeral of Durango made an expedition of inspection to the upper Southwest. He wrote, "When I was in Bassaraca (Baserac), the general of the Opatas, Don Jerónimo, offered, if I liked, to take me from there to New Mexico in a few days, for he knew a much shorter route than the one I had planned to take to El Paso." The first significant Zuni contact with Anglos began when trappers appeared from 1826 through 1828. (44)

Motive, means and opportunity should be addressed when considering lead shot found in Río Arriba and Zuni. Written history reveals the opportunity for balls of Middle New World or Spanish lead to appear at Hawikku and Tiguex as soon as forty years after Coronado. There is evidence supporting the likelihood that firearms, lead, and discharging of firearms occurred at Zuni during one or all of the Chamuscado-Rodríquez, Espejo-Beltrán, and Oñate visits. Some Hawikku visits were lengthy and offered greater opportunity to leave shot there. Beltrán and some two dozen people, including several soldiers, remained at Hawikku-Halona for two months in 1583 while Espejo roamed to the west. Shot from that visit are possible at Hawikku. The Oñate visit to Hawikku in 1598 lasted over three weeks, followed by other visits of unknown duration in 1604 and 1605, and shot could have come these occasions. Other lead balls could have appeared at any time after Oñate arrived in 1598.

The first three opportunities for lead carried by Spaniards to appear at Tiguex after Coronado departed are represented by brief visits of few people. The thirty-one members of the Chamuscado party were there less than two weeks, Espejo and his group of forty were there about two weeks, and Castaño, with twenty or fewer men, was there less than a week. Humaña was likely at Tiguex, but with an unknown number of people for an unknown length of time. Although lead found at Tiguex could have originated with any of these travelers, an even greater opportunity for lead to appear in Tiwa country is provided by the Oñate colonization of New Mexico, which brought a flood of lead. Given the presumed wide range of the colonists, lead from those settlers could be the source for shot found at Tiguex.

The mention of arquebuses in the written record is common. Testimony by Chamuscado expedition members Pedro de Bustamante and Hernando Gallegos included relating that each carried arquebuses and that such firearms had been used to kill buffalo. Gallegos wrote, "We fired quite a few arquebus shots, at which the natives were much frightened…," and, "the arquebuses roared a great deal and spat fire like lightening" and "[Pedro de Bustamante] picked up a bit of hay, started a fire by means of an arquebus, and prepared to burn the pueblo." Kessell reported that on occasions the Spaniards of the Chamuscado party "inspired both respect and friendship by firing their arquebuses." Gallegos reported that when the Chamuscado expedition arrived back in Santa Bárbara, "we were well received… and given a warm welcome. We fired a salute to the town with our arquebuses…" With respect to the use of firearms by the Espejo party, Kessell wrote, "The Spaniards camped two arquebus shots away [from Pecos]… When they asked for food, the natives… pulled up their ladders and refused to come down… Espejo and five soldiers, threatening to burn the place, entered and began firing their arquebuses in the plaza and streets..." Castaño de Sosa reported that the raising of the cross at pueblos in Río Arriba was accompanied by "the sound of trumpets and arquebus shots." Historian Marc Simmons reported on events of the September 1598 festival during the dedication of Oñate's church at San Juan Bautista: "At week's end, the festival concluded with a thunderous volley of artillery." These examples point to a wide-ranging, continual use of arquebuses as the means for distributing lead shot in Río Arriba and Zuni, as well as pointing out the motives for discharging these weapons. (45)

The record of materials carried by the Oñate party reveals the importance of lead and firearms, as well as information on where at least some of the lead was obtained. "[On 9 February 1597], at the mines of Todos Santos, the governor [Oñate] presented [to the inspector] 100 quintals of lead. It had been bought from Diego de Zubía, alcalde mayor…" The following 3 January 1598, an inventory found that only 78 quintals and eight pounds remained. About three weeks later the Oñate Expedition departed Arroyo San Gerónimo, north of Santa Bárbara, after the final inspection. The second day's march passed by El Torrente de la Cruz and reached "the mouth of the Todos Santos mine," where the party spent the night. Jackson provided a verbal location for these mines, and I understand them to be about forty kilometers north of modern Parral, Chihuahua. Although there is no record of such, it is not inconceivable that Oñate bought still more lead at Todos Santos. If he did not, then the last recorded amount of lead carried by Oñate was 17,168 pounds, all from Todos Santos mine. (46)

In addition to the lead for the unified expedition, individual members carried personal lead and powder, attesting to the communal use of firearms. The following quotations respecting gear taken by expedition members are taken from various records of the Oñate Expedition: "two molds and a gunner's iron ladle for making balls;" "eight pounds of ammunition;" "twenty-five pounds of powder;" "two pounds of powder and four of shot;" "half an arroba (~12.5 lbs.) of powder;" "one barrel of powder containing about half a quintal (50 kg, 110 lbs.);" "twenty-five pounds of lead;" "one mold for making shot;" "twenty-five pounds of lead made into bullets and buckshot;" "one arroba (25 lbs.) of powder and half an arroba (~12.5 lbs.) of ball." The records include numerous instances of expedition members carrying tools for gunsmithing. (47)

This evidence provides the means for lead shot and firearms arriving from Mexico, as well as a motive for the discharge of them, as early as 1581, and the consequential opportunity for lead shot to appear at Hawikku and Tiguex. The reports show that Todos Santos lead was purchased by at least one traveler, Oñate, such lead being purchased near Santa Bárbara, thereby providing a source of lead to any northbound traveler and demonstrating the assertion that travelers bought lead along the way.

Respecting the written history, the availability and use of firearms, and the convenience of lead mines along the road, I reasoned that although the early Río Arriba explorers, or those even later, could not be excluded as the bearers of the Spanish lead balls from Hawikku and Piedras Marcadas, that it was most likely that these late sixteenth-century adventurers carried Middle New World lead, particularly Mexican, rather than Spanish shot. The shortage of lead that existed in Spain at that same time, coupled with irregular maritime transportation, suggests that Spanish lead was probably not being exported to Mexico. As for the source of the late sixteenth-century explorer's Middle New World lead, it seems reasonable that lead arriving in Río Arriba after Coronado was more likely from northcentral Mexico than from Tarasca or Central America because of the different travel route. Moreover, being as lead from northcentral Mexico was probably unavailable to the Coronado Expedition, it is improbable that Coronado carried any from there, whereas he traveled through the Tarascan mining region and could have obtained lead along that route. Given these parameters, just being able to confidently identify Tarascan lead (Coronado route) and northcentral Mexico lead (post-Coronado route) provides compelling evidence for assigning a relative date to balls of Mexican lead.

Unfortunately, lead isotope analysis was inconclusive as to whether the two Middle New World lead shot found at Hawikku and the single Middle New World ball found at Piedras Marcadas were Tarascan, northcentral Mexican or Central American because the shot appears amongst all three imprecisely bounded isotope populations. Consequently I cannot assign the Middle New World lead found at Hawikku or Piedras Marcadas to a particular expedition or event – it may or may not be from the Coronado Expedition. On the other hand, because of historical reasons, I am confident in assigning the Spanish lead found at Hawikku and Piedras Marcadas to the Coronado Expedition.

Lead isotope ratio analysis identified one shot found at the Jimmy Owens site as Spanish lead and three balls as being Middle New World lead. In my attempt to determine the event(s) that caused this lead to be at the location, I could find no written evidence that the Jimmy Owens site was ever occupied or visited by Spaniards after Coronado departed there in 1541. Archaeologist Jonathan E. Damp reported, "The Owens site is a Coronado campsite in Texas that has no later component so all artifacts found at the site should pertain to the Coronado Expedition." Despite this claim, I reported a Spanish military copper button from the Jimmy Owens collection that dates 1710 – 1750. (48) How it arrived at the site remains unknown, but it offers, nevertheless, evidence of Spanish metal unrelated to the Coronado Expedition.

Historical evidence exists for the claim that Spaniards visited the geographical region containing the Jimmy Owens site. Excursions to the east by the Spanish military commenced as soon as Oñate arrived in Río Arriba and continued until Mexican independence. As early as September 1598, Oñate sent scouts from Río Arriba to the headwaters of the Canadian River near Amarillo, Texas, and in 1601, Oñate led an expedition that reached central Kansas. (49) Excursions such as these persisted during the time represented by the button found at the Jimmy Owens site. Oklahoma historian Alfred B. Thomas provided two maps of Spanish excursions in his summary of Spanish exploration east from Santa Fe from 1599 to 1792. The maps trace the reported trails of Spaniards roaming east from Río Arriba, and they serve to illustrate the range of Spanish excursions and to point out that the Jimmy Owens site falls well within the reach of Spanish exploration, both reported and unreported. (50)

For the same reasons affecting the Hawikku and Piedras Marcadas balls, lead isotope analysis was inconclusive as to whether the three Middle New World lead shot found at Jimmy Owens were Tarascan, northcentral Mexican or Central American. Given the likelihood of a post-Coronado Spanish presence in the Jimmy Owens region, and the likelihood that these Spaniards carried lead from Mexico, while at the same time acknowledging that the Jimmy Owens site was a water source that attracted long-distance travelers, one cannot exclude post-Coronado Spaniards as possible bearers of the three balls under consideration. However, given the association of the three Jimmy Owens shot with accepted Coronado artifacts, and the isotopic possibility that the lead could be Tarascan, it is much more likely that the balls of Middle New World lead found at Jimmy Owens are indeed from Tarasca and the Coronado Expedition rather than from a later, unreported Spanish excursion. With respect to the shot of Spanish lead found amongst dozens of accepted Coronado artifacts, I concluded that it almost certainly belonged to one of Coronado's expeditionaries.

Lead isotope analysis concluded that balls of Spanish lead were present at all five confirmed or suspected Coronado Expedition sites that my team analyzed. As a consequence of the lead analysis, I modified my ever-evolving exploration model to include the likelihood of Spanish lead at Coronado sites.

The written history of post-Coronado Spaniards arriving in Río Arriba impacts any temporal interpretation of metal artifacts found in that region. Given that only about forty years separate the departure of Coronado from Río Arriba and the arrival of the Chamuscado-Rodríquez and the Espejo-Beltrán parties, and that only about fifty-six years separate Coronado from the 1598 Oñate arrival, it follows that sixteenth-century objects were carried by all these parties. This complicates any effort to assign a Coronado presence based purely upon the presence of sixteenth-century artifacts.

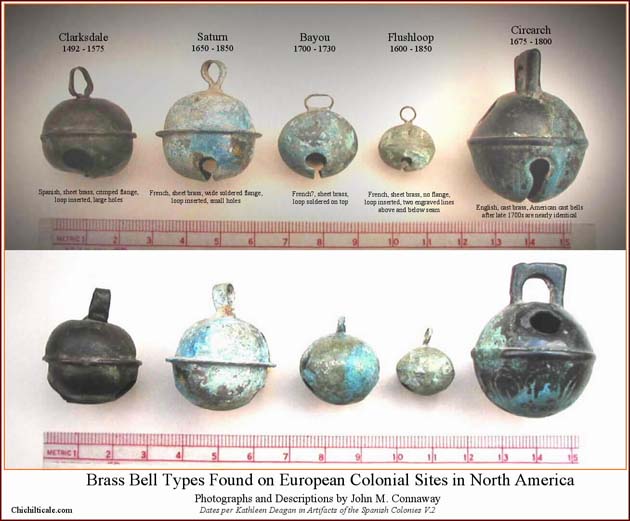

The Chamuscado-Rodríquez party carried "provisions and articles for barter." Recorded testimony of the soldiers accompanying the party included an example of barter: "We gave them some iron, sleigh bells, playing cards, and various trinkets… They gave us corn, beans, calabashes, cotton blankets, and tanned buffalo hides." Diego Pérez de Luxán, reporting on the Espejo-Beltrán expedition, wrote that on 23 February 1583, at Cachiti (Katisthya, modern San Felipe, New Mexico), "We bartered sleigh bells and small iron articles for very fine buffalo hides." Antonio de Espejo reported that he "gave beads, hats and other articles" and "trinkets of little value" to the Indians. In 1590, Captain Juan Morlete was sent to arrest Castaño de Sosa. His instructions included having "small articles of little value which you can carry with you and apportion among the natives." Oñate's contract called for him to carry "articles to trade and to give to the Indians." Two inspections of his cargo reported on "barter articles" and these included beads of many varieties, combs, knives, hatchets, scissors, needles, mirrors, yarn, earrings, hats, hawks-bells, medals of alloy, jet rings, alloy finger rings, thimbles, tassels, amulets, whistles, glass buttons, flutes, awls, thread, and children's trumpets. These examples show that beginning in 1581, and accelerating rapidly in 1598, appeared an infusion of Spanish objects into Río Arriba. (51)

With respect to specific items, these reports demonstrate that Spanish copper bells reappeared in Río Arriba just thirty-nine years after Coronado departed, and that beads reappeared by at least 1582 with Espejo. Oñate alone carried "three bunches of glass beads, each one containing 10,000 beads… [and] forty-five thousand small glass beads… [and] forty-six bunches of small glass beads of 1,000 beads per bunch." Respecting bells and beads, archaeologist Kathleen Deagan published data proposing that 1550 and 1575 were dates of style termination of certain Spanish copper bells and that some bead styles became extinct between 1540 and 1581. Even if such were indeed the case, specific styles of bells and beads alone might not serve to distinguish between Coronado and post-Coronado classification of such objects found in Río Arriba because obsolete styles might have been carried by arriving Europeans. (52)

The Coronado Expedition carried crossbows. I have previously reported that archaeologist Frank Gagné claimed that the "Chamuscado – Rodríquez – López and the Espejo – Luxán expeditions" also used crossbows. Were this the case, post-Coronado crossbow boltheads could have reached Zuni or Rio Arriba with those 1580s expeditions. However, Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint strenuously dispute Gagné's contention. "In this unsupported assertion, Gagné was simply wrong; there is absolutely no mention of crossbows in the documentation of either of those expeditions.” In the early 1990s the Flints studied the published documents dealing with both of those expeditions, as well as those of twenty-four other sixteenth-century expeditions, specifically picking out all references to items of material culture, including arms and armaments. They found no references to crossbows in the documents relating to either of those expeditions. My own research found no mention of crossbows in the accounts of Castaño or Morlete, or in the muster of the Oñate expedition.

There is, however, an unfortunate insinuation that crossbows in the New World were not obsolete in 1596. Pedro Ponce de León, a rival of Oñate for "exploration, pacification and settlement of New Mexico", in his attempt to gain the royal contract, claimed he offered more than Oñate. Included in this greater offering were "fifty crossbows," these being items specifically mentioned as absent in the Oñate inventory. Military arms historian Harold L. Peterson describes the Ponce de León offering as the "last known reference to crossbows for use in America." Oñate, not Ponce de León, however, won the contract, and Hammond and Rey presented evidence that these fifty crossbows never reached New Spain. Providing still more evidence of the disappearance of crossbows, Peterson wrote, "By the middle of the 16th century, however, the crossbow had been largely superseded as a military weapon in Europe… A few crossbowmen were listed in the Spanish forts of St. Augustine and Santa Elena in 1570, 1573, but they were distinctly of secondary importance." The Flints allow that "after the 1560s, there may have been an occasional stray [crossbow], but they were definitely no longer a weapon of choice and were definitely not present in numbers sufficient to account for the many crossbow boltheads that have been recovered in recent years in the Southwest." Haring reported that while crossbows were mandatory on vessels in 1552, by 1573 they were "superseded by the more effective arquebus." Given this history, crossbow boltheads in the Southwest are almost certainly from the Coronado Expedition. (53)

When interpreting the age of a metal artifact specifically from Hawikku, one must keep in mind the number of people, the dates, and the duration of presence of groups that could have left metal residuals there. The Flints estimate that 2,000-2,800 people began the expedition. Europeans, not Indios Amigos, were almost certainly the dominant metal-bearers of the excursion. At the time of the conquest of Hawikku the expedition was divided. Beginning on 7 July 1540, the 80 - 110 European metal-bearers and more than 700 Indios Amigos of the Advance Party began the occupation of Hawikku. Some three months later, on about 8 October 1540, the Following Army joined the Advance Party, thereby increasing the population of metal-bearers to 400 European men-at-arms plus European women and children. The Following Army stayed for twenty days before departing toward the east. In total, this first large occupation lasted nearly four months and was likely the biggest occupation ever of Hawikku. (54)

The next and final Coronado occupation of Hawikku occurred when the Retreating Army of 1,550-2,350 people arrived in early spring of 1542 on its return to Mexico. The expedition was undivided at that time, thereby providing a second large gathering of European metal-bearers, perhaps about three hundred. Because of normal usage and attrition, these bearers likely had less metal than those in 1540. The Retreating Army departed Hawikku for New Spain on 5 April 1542 after having occupied the pueblo for a duration likely measured in days not weeks, a time span that provided another opportunity for European articles to have been lost and to become future artifacts. (55) These occupations by Coronado total about four months of presence at Hawikku by at least one hundred metal-bearers, with one of those months having more than four hundred metal-bearers.

In contrast to the Coronado occupations, the first measurable European presence at Zuni after Coronado occurred in 1583 when about thirty members of the Espejo – Beltrán party sojourned for two months at Hawikku - Halona. There is no record of a larger expeditionary party arriving after Espejo – Beltrán. These numbers show that the Coronado Expedition stayed longer and contained more European metal bearers than any other non-Native American presence ever at Hawikku. With this dominance of presence at Hawikku by Coronado metal-bearers, it is relevant to artifact interpretation to recognize that the cargo of the Coronado Expedition during its time in Hawikku included many domestic items. Such a concentration of European domestic items did not ever occur again at Hawikku. This significantly elevates the likelihood of domestic artifacts found at Hawikku being of the Coronado Expedition rather than those of later travelers.

Interpretation of the age of metal artifacts found in Tiwa country, just as at Hawikku, must consider the number of people, the dates, and the duration of presence of groups that could have left metal residuals there, as well as conditions at Tiguex itself. Of all the groups of metal bearers arriving prior to Oñate in 1598, the Coronado assemblage of 1540-1542 was by far the most numerous and of the longest duration. By comparison, the much smaller Chamuscado, Espejo, Castaño and Humaña parties were in Tiwa country only briefly, thereby offering less opportunity for objects to be lost or discarded than had been the case with Coronado. The brevity of these later visits was likely due to abandonment of Tiguex, a factor that must be considered when interpreting the source of metal artifacts found there. Riley described the invasion of Tiguex by Coronado as the effective beginning of the end of Tiguex. "A significant development in the winter of 1540-41 was the destruction of all the Tiguex pueblos… Thirteen of the towns deserted by the Indians were looted and dismantled by the Spaniards… By the spring of 1541 Tiguex was largely destroyed. All the towns were occupied or burned." Forty years later, when Chamuscado arrived, "Tiguex was making a recovery but the scars of the Coronado occupation were still very real… Except for Chamuscado, no Spanish party after Coronado really had much interest in Tiguex, probably because there was little left but poverty. Espejo concerned himself with the western pueblos and the Keres, and Castaño with Pecos, the Tewa, and Keres. Oñate, though he occupied the whole pueblo area, centered his activities on the Tewa and the Keres." Riley points out that "By Oñate's time, the first missionaries did not seem to consider the area very important – only two missions were established there, both around or after 1610 with two others made visitas. Missions were at Sandia and Isleta and visitas at Puaray and Alameda. These four towns were the Tiguex of the 17th century." Respecting this history, it is most likely that sixteenth-century Spanish artifacts found in Tiguex are from Coronado, although one cannot exclude such artifacts as being from a later Spanish presence. (56)

The historical record best guides interpretation concerning the bearers of Spanish lead. This record shows that firearms, therefore lead, traveled with the Coronado Expedition. I have pointed out that the expedition had access to Tarascan lead, not northcentral Mexico lead, thereby increasing the likelihood that Mexican lead of that expedition was from western Mexico. Lead and lead shot were amongst the inventory of the post-Coronado expeditions to Río Arriba. I have demonstrated that this lead was most likely from northcentral Mexico, readily available as a by-product of the extensive post-Coronado silver mining in that region, thereby essentially eliminating it from being a Coronado residual, and I have reasoned that it is unlikely that post-Coronado expeditions carried Spanish lead to Río Arriba because of the lead shortage in Spain and the availability of Mexican lead along the travel route.

Exactly where a particular lead shot was found strengthens or weakens its relationship to Coronado. I previously proposed that "Spanish lead found within specific geographical corridors is diagnostic of the Coronado Expedition." (57) My team currently considers Spanish lead shot found along the route of the Coronado Expedition from the Río San Pedro to the Río Bermejo campsite (Río Zuni southwest of Hawikku) to be artifacts that are temporally restricted to the sixteenth-century, thereby indicating the presence of the expedition, and joining crossbow boltheads, and certain bells and beads, as decisive evidence of the Captain General along that trace. The team's current hypothesis for lead shot found at Hawikku and beyond is that shot made of northcentral Mexican lead are almost certainly of post-Coronado age, and that lead shot of Tarascan or Spanish sources are more likely than not a product of the Coronado Expedition. Consequently, when Spanish lead is discovered with generic artifacts that could be sixteenth-century, especially if found south of Hawikku to the international border, the lead serves to elevate the likelihood of these non-temporal artifacts being residuals of the Coronado Expedition.

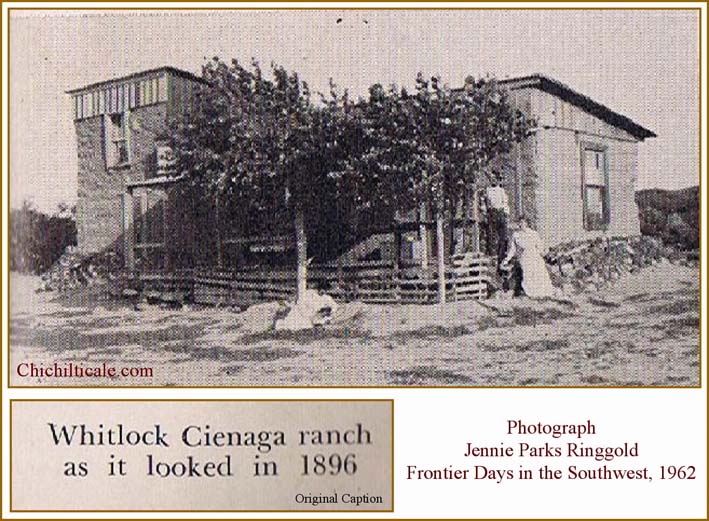

The discovery of Spanish lead and sixteenth-century nails and tacks at Doubtful Canyon supports my exploration model and extends the artifact-evidenced Coronado Trail to the modern Arizona – New Mexico stateline. This success in Doubtful Canyon accredits the team's January 2005 decision to explore Doubtful Canyon before Whitlock Cienega (Cienega Salada) as the next camp north of Apache Pass.