The earliest record of the site currently known as Kuykendall Ruins is from Amerind Foundation card Arizona:FF:2:2, dated June 15, 1934. The site is called Light Gopherhole. It is described as a “Large ruin northwest of Granthams Store (3/4 mile).”

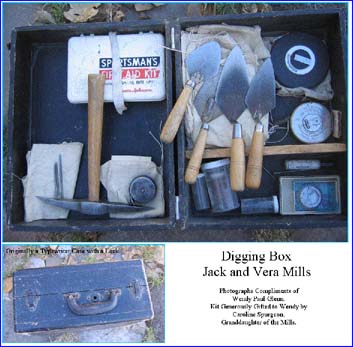

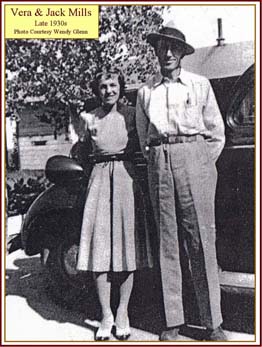

On January 7, 1951, Jack and Vera Mills, avocational archaeologists and associates of W. S. Fulton, Founder of the Amerind Foundation, began formal and professional excavation at what they called the Kuykendall Ruins. Jack was 59 years old and Vera was 51 when they began the project. Most of the fieldwork was done on weekends when Jack was not working as a carpenter. Vera did all the writing required for publication and was responsible for restoration of the ceramics.

The Mills efforts lasted ten years, during which time they discovered red walls on some of the buildings they uncovered. They published their findings in 1969. That same year of publication, the couple returned to the site and excavated one more house. The results of this excavation were published in August 1969. The 1969 excavations were the last known formal activities of public record conducted at Kuykendall Ruins. The current landowners spoke with two archaeologists in 1999 about renewing work at Kuykendall Ruins. The two scientists showed a complete lack of interest, each advising the landowners that the site offered nothing that had not already been learned.

The Mills arrived in Arizona from Los Angeles during the Depression. Jack Pierce Mills, born 23 April 1892 near Danville, Kentucky, died in 1994 at age 102. Vera Marie Burton Mills, born 16 March 1900 in Iowa, died in the year 2000 at age 100. Jack and Vera were married on 27 June 1917 at the home of Vera’s parents in Solano, New Mexico – their marriage spanned more than 77 years.

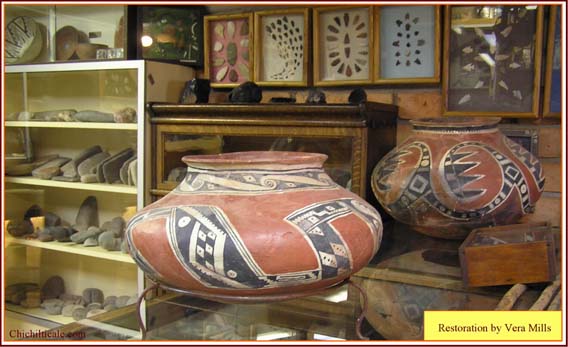

The Mills recognized the beauty of the artifacts they found at Kuykendall. Vera took great care and showed remarkable tenacity and skill with restoration efforts on the ceramics excavated. “If I ever found one that had never been disturbed, I’d tell people that I thought I had died and gone to an archaeologist’s heaven,” Vera quipped. “Of all the pottery found only about 2% of the vessels were found intact. Fitting the pieces together to restore a bowl, pot, or vase is worse than working the most complicated jigsaw puzzle.” Since only two pots out of a hundred would be unbroken, Vera would spend months at home after a dig restoring pottery – one of which had been broken into 525 pieces. “It’s been broken 500 years, so it’s not going back together just like it was,” she said. But she became so proficient at her craft that she taught classes on restoration.

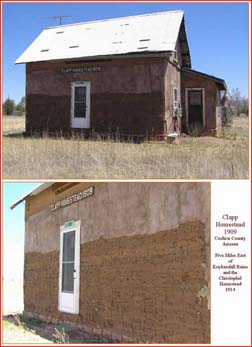

Jack and Vera Mills built a “Study Museum” to house their “prehistoric Indian material.” A visitor described it in 1967. “The floor area is 14 by 42 feet, with living quarters on the second floor. The Mills’ built it of adobe and it included a rock fireplace composed of rocks from many parts of the county. An added attraction is a petrified section of wood which is included in the fireplace. Everything is neatly catalogued and displayed in cases and shelves around the large room. Nearly 6,000 people have visited the Mills’ museum since it was built in 1947.”

During the early 1980s the Mills decided to place their collection in another museum. Two European museums bid on the artifacts, but the Mills wanted their work to remain in Arizona. In 1983 the Eastern Arizona College Foundation acquired the collection. Today the legacy of this remarkable couple graces the Student Services Building at Eastern Arizona College in Thatcher.

For the purpose of our initial research design, we reported ground disturbances at the Kuykendall site beginning during the late 19th or early 20th centuries.

DISCLAIMER: We have NOT conducted a title search to determine the earliest occupation of the site by non-Native Americans. It is likely that non-Native American occupation did not occur until after the American Civil War. “Modern” artifacts found at the site are as old as 1888.

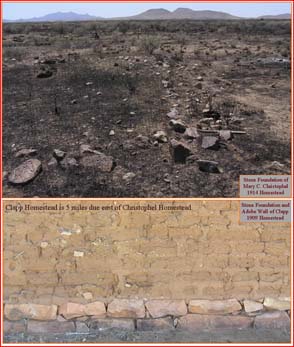

William R. Turvey patented the actual Kuykendall Ruins site on April 15, 1913. Artifacts discovered at his homestead site include buttons marked “Copper Queen Store,” a famous mercantile emporium that was built in Naco, Arizona in 1900 and that operated until the 1930s, and a silver garment clasp stamped 1896. Three other homesteaders patented land adjoining Turvey. Additional early settler period artifacts were found on these sites. An 1888 dime was found on the James Wadkins homestead patented on April 22, 1914, a Leader shotgun shell dated 1901 was found on the homestead of Charlie Eastep patented on August 26, 1914, and a silver button stamped 1924 was found on the homestead of Mary Christophel patented on June 3, 1914.

Being as the Homestead Act of 1862 required a homesteader to build a house, dig a well, plow at least ten acres, build some fences, and actually live on the site, it is fair to suggest that Turvey arrived at Kuykendall Ruins no later than April of 1908, and that Wadkins, Eastep, and Christophel arrived no later than 1909.

Personal communication with at least six “ol’timers” suggests that the Kuykendall site eventually became known as Cooper’s Farm. Cooper owned the site until the middle 1940s. At that time Leslie and Katie Kuykendall bought the site and kept it until June 1962, when it was sold to Frank Sproul, who sold it immediately. The current owners are four members of the Donka family. Local ol’ timers continue to refer to the site as the Kuykendall Place.

This local oral tradition has credibility supplied by Amerind Foundation card Arizona:FF:2:1, the 1952 card for Kukendahl (sic) Site. Written on the card is “Kukendahl Site also known as Cooper’s Field near Granthams.” The Mills report ending their excavations in 1961, and the termination of work may have been associated with the pending sale of the property.

Prior to the Mills arrival at the site for excavation, the land had been disturbed. The Mills reported “remains of an old homestead” and that “the plowed field of this homestead destroyed part of the village.” The Mills reported that some buildings “had been partially destroyed by an earlier excavation and the early homesteaders activities” and that a “complete house had been destroyed by farming, this also having been done by the homesteader.” The Mills mention a number of times finding signs of “previous excavations” and “evidence of metate hunters using a punch rod.” These “excavations” were most likely holes left by looters.

The land was also disturbed during the excavation. The Mills reported “several loads of dirt were hauled away. After this, dirt from the floor being excavated was used to back-fill the area previously dug out.” While excavation was being conducted the site was vandalized. “The State Highway gravel crew, who were then removing gravel from a pit a little west of the area, decided to do some souvenir hunting on a large scale. They used highway bulldozers and completely destroyed the large compound and the remaining part of another compound.”

According to a member of the Kuykendall family, the Mills smoothed the land after their excavation ended. This same family member reported that a few years after the Mills left a “dozer came in and tore hell out of the land,” and that during the period 1980 – 1985 “dozers came in and ‘knifed’ out all the mesquites.”

Natural processes have affected the site. The Mills report “During the summer of 1954 heavy rains brought down flood waters of sufficient depth to cover much of the mound. One wonders how many times this may have happened in the past.”

A member of the Kuykendall family recalls that paving of the highway from Pearce to the Chiricahuas began in the middle 1940s. During that operation a gravel pit to supply road building material was dug on Kuykendall Ruins. The gravel pit later became a county dump, complete with an electrified building on a cement pad. When this operation was discontinued, the pit was covered over with dirt brought from a distant location. Since that time no permanent structures or land alternation operations have occurred on the site. Debris from the dump remains on the surface away from where the pit was covered. In addition to scattered dump refuse, the site is littered by thousands of pieces of trash left for years by undocumented migrants passing through. For every artifact of interest discovered, hundreds of pieces of metal litter are detected and removed. Oftentimes weeks pass between discovery of artifacts that are even remotely interesting, and the vast majority of these prove to be unrelated to the Coronado Expedition. The task is tiring, tedious, failure-prone, and overwhelming to the uninitiated.

Surface artifact collecting has occurred for as long as travelers and settlers have been present. Such collecting is generational. Nugent Brasher encountered two families of surface collectors in 2006 who claimed that their grandfathers had first brought them to the site and that they were returning with their grandchildren. This suggests four generations of surface collectors. These collectors have left their garbage strewn over the site, as well as buried in the holes they have dug.

It is obvious that the ground at Kuykendall Ruins has been highly disturbed by humans engaged in manual labor and humans utilizing heavy equipment. Surface collecting has been intense over at least 75 years. No archaeological interest has been expressed since the Mills left the ruins. Truthfully and unfortunately, this site must be considered neglected.

Our current efforts at Kuykendall Ruins began in late 2005 and continue today. We have invested both capital and labor in the program, and we are dedicated to continue providing these resources. All this investment is from private individuals working on a volunteer basis. We believe that the resources we bring to the project will help to rejuvenate interest in Kuykendall Ruins and to instill confidence that it is the site of the fabled Red House.