On the Day of the Dead in 2011, I received a message from Michel Nallino of Nice, France. That communiqué requested my permission for him to reproduce selected photographs from the Chichilticale.com website for use in a biography devoted to Marcos de Niza. I gladly granted permission, and that biography is now uploaded and available for viewing. The complete stream of messages shared by Michel Nallino and me are below.

From: Michel NALLINO

To: Nugent Brasher

Sent: Mon, Oct 31, 2011.

Subject: Ask for permission of use of some of your pictures

Dear Mr Brasher,

I am a private researcher, currently writing the 3rd and last volume of a biography dedicated to Fray Marcos de Niza. In this volume I treat of the Coronado expedition, and Chichilticale location, and I would like to use as illustrations some of the photographs of artifacts that you have published on you web site. Do you allow me to use them in my work? Under what license, or with what credit sentence (with permission of the author...)?

My works are freely available online, on Internet archive, under a Creative Commons by-nc-nd license. You can access them from the following page: http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=creator%3A%22Michel+NALLINO%22

Waiting for your answer,

Best regards,

M. Nallino

From: Nugent Brasher

To: Michel Nallino

Sent: Tuesday, November 01, 2011.

Subject: Re: Ask for permission of use of some of your pictures

Hello Michel,

Your thoughtful message reads, “I would like to use as illustrations some of the photographs of artifacts that you have published on you web site. Do you allow me to use them in my work? Under what license, or with what credit sentence (with permission of the author...)?

Yes, Michel, you may use as illustrations some of my photographs. Thank you for your communication about them. As for the license, please use the following…. With permission of Chichilticale.com

Please let me know when you have the photographs uploaded. I will enjoy seeing them in your publications. Good luck with your research.

Nugent Brasher

From: Michel NALLINO

To: Nugent Brasher

Sent: Tuesday, 1 November 2011.

Subject: Ask for permission of use of some of your pictures

Hello Nugent,

Thank you for your permission. I will let you know when my work will be online and I will send you the URL (it will be stored on Internet Archive, "archive.org"). Hope you read French! ;-)

I have read your papers in New Mexico Historical Review and, of course, I know your web site. I do think you have found Coronado's Chichilticalli camp.

But I think that this camp is not the Chichilticalli that Fray Marcos planned for being a Spaniard basis, with ship transports from / to New Spain. Coronado himself wrote (in the letter from Cibola, 3 August 1540) that he could not use the same way as Fray Marcos used and was obliged to go deeper and in the lands, so he found Chichilticalli at 15 days from sea while Fray Marcos had told it was only a few leagues far from sea.

It was a bit hard to find the meaning of this, until I noticed that, at 20 or 25 km East of Coolidge, AZ, the valley of the Gila River becomes wider and wider, up to 5 km wide. I imagine that, if Fray Marcos had seen the Gila at that place when there is a lot of water, he could have thought to see an estuary going to sea. The Gila flows West, like in the Relation "at 35° the coast turns West"; we are at 33°, instead of 35° in the Relation, but his could be due to error in instruments, or to the will to give imprecise information to Mendoza's competitors for the conquest.

At Coolidge, there is Casa Grande, and Casa Grande is, as I am convinced, Fray Marcos' Chichilticalli. While admitted during the 19th century, this has been criticized by Bandelier, who noted that the surroundings of Casa Grande don't match the descriptions by Castaneda or Jaramillo. But this criticism is no longer acceptable if there are two Chichilticalli!

Fray Marcos planned, with Mendoza and Coronado, a naval expedition (Alarcon's one) to reach Chichilticalli and to bring to Coronado the "heavy luggages" of his army. But Alarcon failed to enter the Gila River and entered the Colorado River. And Coronado didn't succeed in following the same paths as Fray Marcos (a large army cannot use the small paths used by a few pedestrians), and when he asked Indian guides his way for Chichilticalli, he was guided to Kuykendall: the Spaniards did make a big mistake believing Chichilticalli was a proper noun, while it was just meaning "red house" in nahuatl. They asked for "The" red house, and they were guided to "A" red house!

Finally the Spaniards plan of conquest, by land and sea failed because of:

- Fray Marcos misunderstanding of the Gila River widening as an estuary,

- Alarcon entering Colorado and not Gila, then refusing to join Coronado's troops at Hawikuh by land,

- Spaniards misunderstanding of Chichilticalli meaning.

No base for Spaniards, no harbour to send / receive things to / from New Spain, no Spanish colony...

As I say, "Two expeditions, two Chichilticalli!" Of course, this will be addressed in detail in my work.

Best regards,

M. Nallino.

PS: it is difficult to say what Chichilticalli Juan de Zaldivar and Melchior Diaz found. Zaldivar says, in his testimony at Coronado's trial, that Chichiliticalli is far 60 leagues or 70 leagues from Cibola (the two figures come from two different versions of his testimony). This fits well Casa Grande, while not excluding Kuykendall (just a bit above the 70 leagues figure).

From: Michel NALLINO

To: Nugent Brasher

Sent: Sun, Sep 16, 2012.

Subject: Re: Ask for permission of use of some of your pictures

Hello Nugent,

I have put online my third volume of Fray Marcos biography. It can be accessed from: http://archive.org/details/FrayMarcosDeNizaInt

I have used some illustrations coming from your site, "With permission of Chichilticale.com".

Best regards,

Michel Nallino

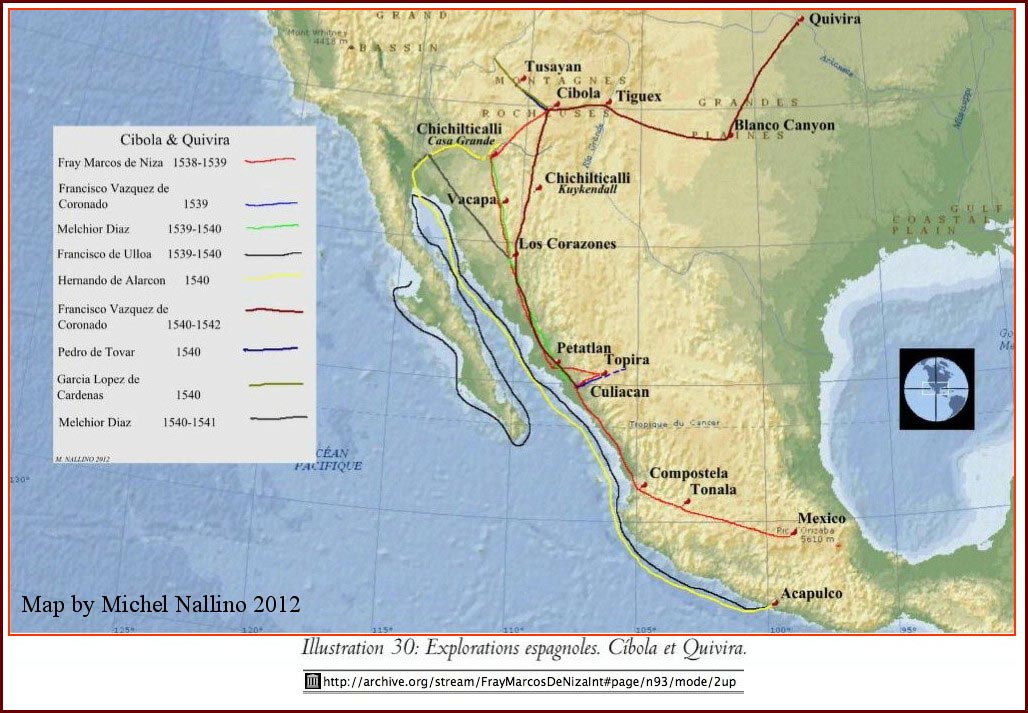

Le Site de Kuykendall is discussed in French by Michel Nallino on pages 282-289 of his authoritative presentation of Marcos de Niza. For readers most comfortable with English, a translation of the French on those pages is provided through the compliments of Gail Bernadine and Michel Nallino. For all readers and viewers, here is the link to Michel’s compelling account of Marcos de Niza and the events surrounding that period in history.

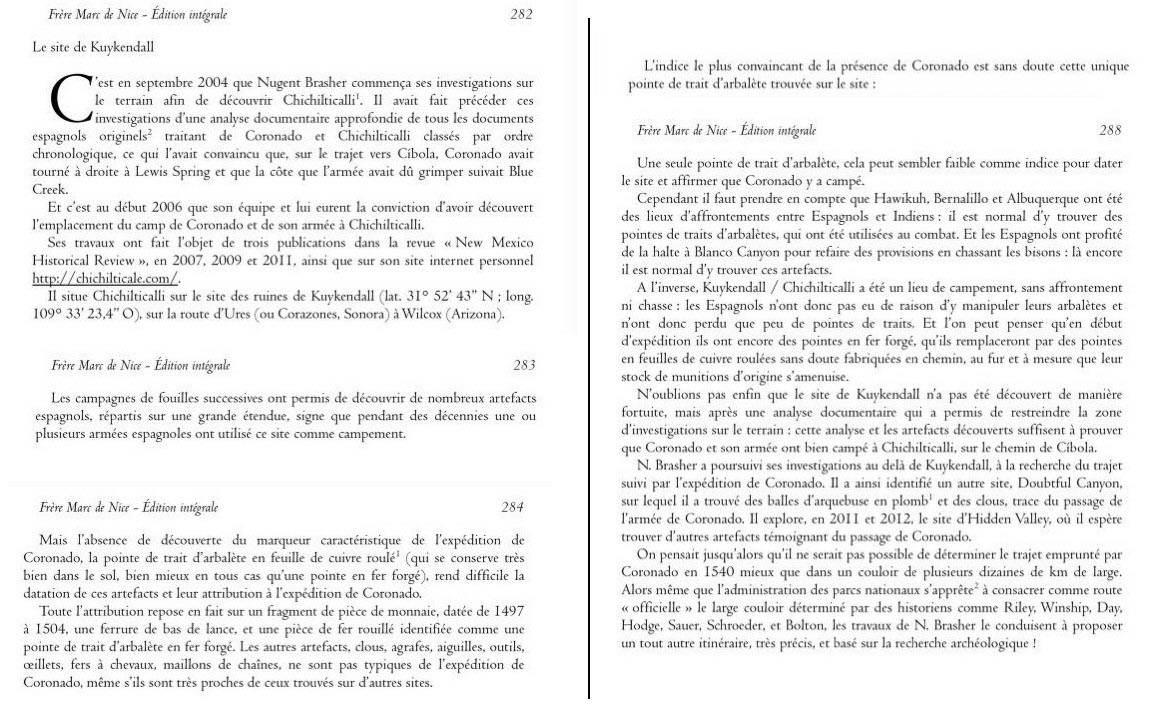

The Kuykendall site 282

It was in September 2004 that Nugent Brasher began his investigations on the ground in search of Chichilticalli. These investigations had been preceded by a thorough analysis of all the original Spanish documents about Coronado and Chichilticalli, arranged in chronological order. This study had convinced him that Coronado, on his way to Cibola, had turned to the right (east) at Lewis Spring, and that the slope that the army had to climb followed Blue Creek.

And it was at the beginning of 2006 that his team became convinced that they had discovered the campsite of Coronado and his army at Chichilticalli.

His discoveries were the subject of three publications in the "New Mexico Historical Review", in 2007, 2009 and 2011, as well as on his own website http//chichilticale.com/.

He locates Chichilticalli on the Kuykendall ruins (lat. 31degrees 52’ 43" N; long. 109 degrees 33’ 23.4" W), on the route from Ures (or Corazones, Sonora) to Willcox (Arizona).

Fray Marcos de Niza - Complete edition 283

The excavations that followed yielded numerous Spanish artifacts, spread out over a large area, a sign that for decades one or more Spanish armies used this site as their camp.

Fray Marcos de Niza - Complete edition 284

However, failure to discover the characteristic sign of the Coronado expedition, the copper crossbow bolthead (which survives very well in the ground, better in any case than a forged iron bolthead), renders the dating of these artifacts difficult, as well as their attribution to the Coronado expedition.

This attribution actually rests on a fragment of a coin, dated between 1497 and 1504, an iron ferrule of a lance, and a piece of rusty iron identified as a crossbow bolthead in forged iron. The other artifacts, nails, clasps, needles, tools, eyelets, horseshoes, and chain mail are not typical of Coronado's expeditions, even though they are similar to those found on other sites.

The most convincing indication of Coronado's presence on this site is without doubt this single crossbow bolthead that was found on the site.

Fray Marcos de Niza - Complete edition 288

A single crossbow bolthead could seem a weak indication for dating the site and affirming that Coronado camped there.

However, it must be taken into account that Hawikuh, Bernalillo and Albuquerque were places of Spanish-Indian confrontation; it is normal to find there the crossbow boltheads used in combat. And the Spanish took advantage of the halt at Blanco Canyon to replenish their provisions and hunt bison: again it is normal to find here these artifacts.

In contrast, Kuykendall / Chichilticalli was an encampment site, without confrontation or hunting: the Spanish had no reason to handle their crossbows and therefore lost few of their boltheads.

And one may consider that at the beginning of their expedition they still had forged iron boltheads, that they replaced with copper boltheads made en route, as their original munitions diminished.

And, finally, let us not forget that the Kuykendall site was not discovered by chance, but after a documentary analysis which permitted restriction of the area to investigate: this analysis and the artifacts that were discovered were enough to prove that Coronado and his army did camp at Chichilticalli, on the way to Cibola.

N. Brasher pursued his investigations beyond Kuykendall, searching for the route of Coronado's expedition. He thus identified another site, Doubtful Canyon, where he found lead musket balls and nails, traces of the passage of Coronado's army. In 2011 and 2012 he has been exploring the site of Hidden Valley where he hopes to find other artifacts testifying to the passage of Coronado.

Until Brasher’s work it was thought not possible to determine the route used by Coronado in 1540 down to more than a corridor tens of kilometers wide. While the National Park Service seems ready to consecrate as "official" the wide corridor designated by such historians as Riley, Winship, Day, Hodge, Sauer, Schroeder and Bolton, N. Brasher's work leads him to propose a whole other itinerary, quite precise, and based on archeological research!